Report on Southeastern Turkey: Part Two

Mardin

By: Zeren Earls - Jul 21, 2008

The city of Mardin is built on top of a 1083-meter high mountain overlooking the Northern Mesopotamian plain and bordering the Tigris River. Its early settlement goes back to nomadic hunter-gatherers in 5000 BC. Since then this region has been ruled by Hurrians, Hittites, Assyrians, Persians, Armenians, Romans, Byzantines, Arabs, and Seljuks, finally coming under Ottoman reign in 1517. In 1919 the French attempted to subdue the area, but withdrew, faced by the resistance of Mardin's citizens. On November 21, 1921 the borders of Modern Turkey were established with the signing of the Lausanne Treaty. Mardin became a local government during the Republic.

As a result of its rich heritage, Mardin is home to different ethnic groups. Many of the Muslim and Christian populations speak their mother tongues, Arabic, Syriac and Kurdish, as well as the official language, Turkish. Church bell towers share the skyline with minarets, while at the same time adorning the city with great architectural wealth. Kasimiye Medrese was our first such example. An impressive portal greeted us at the end of the steps leading to the entry. Built in the 15th century the two-story theological school has a mosque to its left and a reflecting pool in its courtyard. Its simple glamour lies in its arches, double domes and inscribed stone signs indicating the subject taught in each classroom.

The caretaker of the medrese, a Kurdish man with seven children, introduced us to one of them. A beautiful young girl, she was selling her own beadwork along with other children. They had set up tables facing the school, with the Mesopotamian plain as a backdrop. To support their craftwork, we all bought beaded necklaces or bracelets. Then we went on our way for lunch.

At an elegant traditional restaurant, a former Mardin home, we sampled local delicacies. The first course was mint-flavored cold yogurt soup made with chick peas and wheat kernels. Then followed two types of icli kofte (meatballs coated with cracked wheat) boiled and fried. The main course was kazan kebab (lamb with eggplant, onions, peppers and tomatoes) accompanied with pilaf and caper salad seasoned with pomegranate vinegar. Semolina halvah and Turkish coffee topped off the meal. Capers are plentiful in this part of the country and are eaten frequently. Pomegranate vinegar and sumac are favorite flavors in the kitchens of the Southeast, in addition to hot peppers, used in moderation.

The city was festooned with flags along with Ataturk's proverbs stretched across streets in Republic Square because of the national holiday. Walking around, we dropped into a shop selling almond sweets, a specialty of the region, where almonds are plentiful. The shop featured the nut, raw or roasted, as well as coated as a sweet in different flavors. The nuts were displayed in big sacs in the open, tempting the visitor to sample and purchase. We indulged.

Four kilometers outside of town we visited the Deyr-ul-Zaferan Monastery, so named in Arabic because of its yellowish saffron-colored walls. The former home of the Syrian Orthodox Patriarch (1166-1932), the monastery is still an important center for the church, although the patriarchate is now in Damascus. It was built in the 5th century AD on the original site of a Roman fortress dating back to the 3rd century. The three-story monastery sits on top of an ancient sun temple on a mountain slope. A priest with long beard and flowing black robe gave us a tour of the complex, which reached its present size in the 18th century, including three Byzantine churches, dormitories, a school, a cemetery, and cells for seclusion. In Syriac this place is called Fadayso, meaning "paradise".

Kirklar ("The Forty") is the most active church in Mardin. It is entered through an old, heavy iron gate. It stands on the east end of a long courtyard, and is supported by arches upon twelve thick columns. The 6th-century church has a rectangular plan, with icons of saints, various hand-made curtains and clothes for the altar. The church takes its name from the forty Christians who lived around Cappadocia and were executed by the Romans in 240 AD.

In the mid-1800s, when Protestantism found sympathy among the Syrian Orthodox Community, American missionaries opened a college and hospital in the region. They educated local Christians, mostly Armenians, until the Lausanne Treaty, and Turkish children afterwards. Missionary activities came to an end in the 1960s and the buildings were transferred to the State.

Mardin is home to 800,000 people, who have accumulated a rich mythology. A myth or folktale pops out from every corner. A favorite one is "Shahmeran" or "The Snake Woman", about a creature with the body of a woman above the waist, and of a snake below. She has horns, a snake's tail and feet made of snake heads. She is considered a symbol of good luck and fertility, and almost every home has a picture of her. In Mardin, where snakes are plentiful, this legendary creature is immortal through the work of coppersmiths and stonemasons, as well as painters and authors.

Stone masonry is a revered profession in Mardin. Because of its durable nature, stone is the preferred material for construction. Most old houses within the city are made of limestone or basalt, cut by hand at nearby quarries. Various specialists, reputed within the trade, cut, grind, draw patterns on and shape the stones. Placing the stone in keeping with architectural design is yet another specialty

Visiting a Kurdish family in one of the stone houses in the countryside surrounding Mardin gave us a glimpse of daily life. People living here, with women dressed in colorful patterned fabrics, depend on spring water for their needs. Pure water descending from the mountain is fed into a channel, which runs the length of the living room under the dining table. From here the water is directed under the stone patio out to a small pond and eventually to the garden, giving life to the plants. The channel of water serves as a refrigerator as well, keeping fruits fresh and drinks cold.

Mardin has eleven districts within the ruins of the city wall. The quarter of Ulu Cami (Mighty Mosque) takes its name from the city's most architecturally recognizable symbol with its segmented dome and bulbous 61-meter-tall minaret. The mosque overlooks the Mesopotamian plain, the "ocean", as called by the locals, and is the single image that consistently appears on postcards, posters and book covers. The mosque sits on a raised foundation of carved stones on a rectangular piece of land. A flower-figured Kufi inscription on its base states that it was built by the Seljuks in the 11th -century. There is a tea garden by the mosque, where we enjoyed the expansive view below over a thin-bellied glass of Turkish tea.

In nearby quarters are many more historic treasures: the post office, the High School of Commerce (a vocational school for girls), Sehidiye and Melik Mahmut Mosques and Zinciriye Medrese, to name a few. According to legend, the latter once had attached to its twin domes a great chain that bore the blue and white bead protecting people from the evil eye of envy; hence its name, which means "chain" in Turkish.

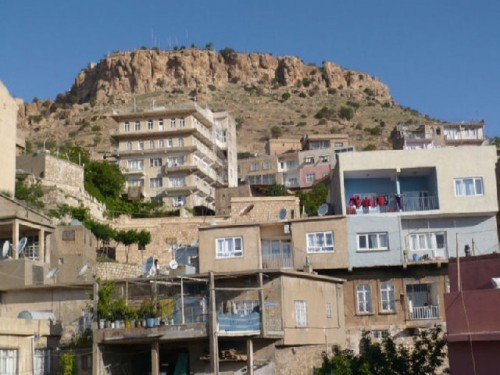

Besides their landmark buildings, Mardin's districts are a maze of narrow medieval streets and alleys, some with steep stairs. The streets are lined with stone houses with flat terrace roofs, many with potted plants. The way the houses are stacked up on the hillside, the roof of one becomes the terrace of another. A walk through the streets reveals interesting metal doors embellished with decorative elements and plaques. The Abbara (a path running under a house) is a characteristic of Mardin houses. These passageways connecting alleys belong to the municipality, while the house above is privately owned. The rubbish is collected by the municipal donkey-service.

Our hotel, the Artuklu, a restored caravanserai built in 1275, was within the city walls in the old town, which has been declared a heritage site by the Ministry of Culture. We enjoyed a buffet dinner at the hotel, which has an old charm, including its small sleeping rooms. Dinner featured dishes made with the region's own plentiful crops: spring soup made with beets and carrots; a variety of salads with chick peas, lentils, almonds and walnuts; and lamb kebab with eggplant. A sweet pastry called tulumba (fluted cylinders of fried dough dipped in syrup) along with fresh apricots and strawberries were the choices for dessert. After dinner we drove to a promontory to view Mardin's nightscape; the hillside shimmered in lights. Having had a long day, we returned to our Caravanserai.