Manet in Black at the Museum of Fine Arts

Realist Impressions in Printmaking

By: Shawn Hill - Jul 25, 2012

Manet in Black

Mary Stamas Gallery (near the Europe at Mid-Century galleries)

Boston Museum of Fine Arts

February 18, – October 28, 2012

Manet in Black feels both personal and opportunistic. It's a way of giving an audience what it wants (always Impressionism, at the MFA) while also deepening our understanding and reveling in the depth of the collection. This entails showing lesser known works by one of the great French painters of the 19th century. If you're an MFA habitué, you can spend your time in this hallway studying etchings, aquatints and lithographs and realize that they function almost as studies and sketches from Manet's formative years. Why not then head upstairs to see some of the actual (or similar) paintings that resulted from these parallel works?

There are only four Manet paintings on display right now in the European galleries, but they come to life anew once one sees the connected compositions and approach to subject matter in the black and white works on paper one floor below. We may not have the magisterial and challenging "Olympia" of 1863, but we have a rough and ready etched version of the motif from 1863. It reveals Manet's intention to blend the servant bringing the bouquet and the cat reacting so humorously at the foot of the bed into the dark shadows of the indistinct room. It makes the courtesan's pale white nudity all the more glaring.

The etchings especially owe homage to one of Manet's idols, Goya. The rich wonderment of this in-house show is that we have what Manet had, Goya and Velazquez and Rembrandt in the museum, now to be seen side by side with the young Realist's efforts. The student has joined the ranks of his masters.

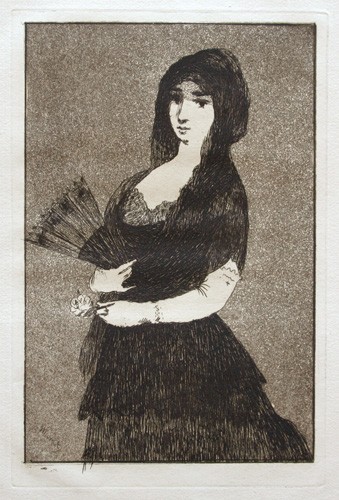

While Goya's prints often satirized human cruelty, Manet merely borrows the Spanish attire and poses. He leaves the mantilla-wearing beauties clad in layers of dark lace against indistinct and flat backgrounds of gray. She becomes a study in femininity and beauty, but informed by the contemporary eye, concerned more with what can be seen than what might be said.

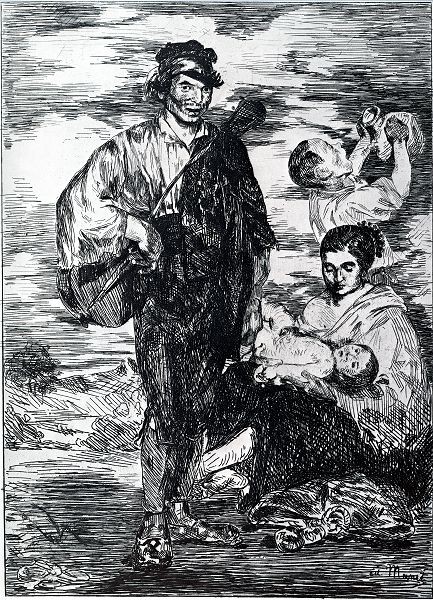

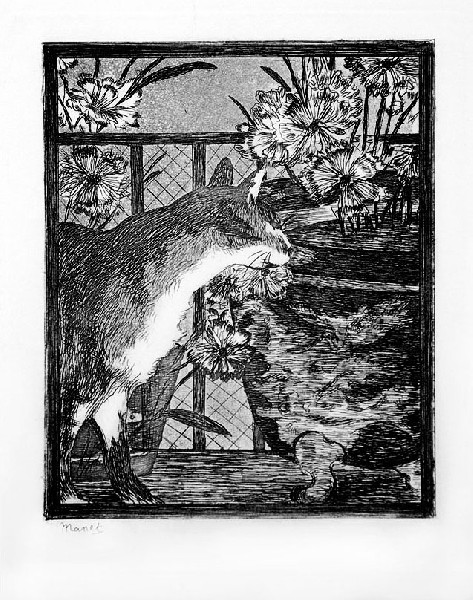

Other etchings look almost like juvenilia, overloaded with a network of rough lines, their genre figures stuck in rather stiff poses. "Les Gitanos [the Gypsies]" tries to imbue some exotic personality, and "Cat and Flowers" contrasts the textures of petals and fur in overlapping layers, the tight and dense composition of patterns borrowed from Japanese printmaking.

It is with the lithographs that Manet's hand really becomes confident and free. What better medium (the closest to drawing with charcoal or crayon on a firm surface) could be used for "The Races," a racetrack scene from around 1870? The bustling, fugitive energy of the crowd is confined to the sidelines of the wide racetrack, while the distant horses thunder towards us from the horizon in exaggerated perspective. Details are hinted by gestural masses of black and directional lines that contrast fugitive clouds and the raked soil of the track. Straddling that line of intent between Realism and Impressionism, "The Races" illustrates how closely connected were those evolutionary artistic steps.

Other charming scenes and portraits are collected by the lithographic stone, with a touch growing ever more light and quick. A café scene with waiters and starched aprons and top hats on hooks is an economical flurry of marks. In a simpatico portrait of fellow artist Berthe Morisot, she looks lovely but a bit disheveled in her dark hat, scarf and ruffled coat.

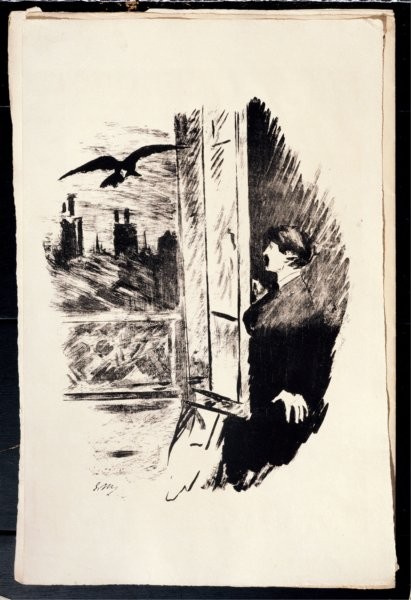

The treasure amidst the treasures is an extended sequence of illustrations representing a transatlantic meeting of the minds. Both Manet and Baudelaire were great supporters of the American author and poet Edgar Allen Poe. His gothic tales seemed to bridge the gap from Romanticism to the Symbolism that would emerge later in the century. Symbolist poet Stephane Mallarme strove to translate "The Raven" into meticulous French, and Manet aids him in every way possible with illustrations that seem to emerge from the mind of the tortured narrator. Flurries of black on white pages, these expressive lithographs capture key moments from the iconic poem, revealing the spectral raven as it perches on a bust of Pallas, or hovers at the window. The whole work represents a congruent meeting of the minds of four great 19th century artists, and is the extreme culmination of Manet's mastery of printmaking.

This rich and unexpected show is not to be missed.