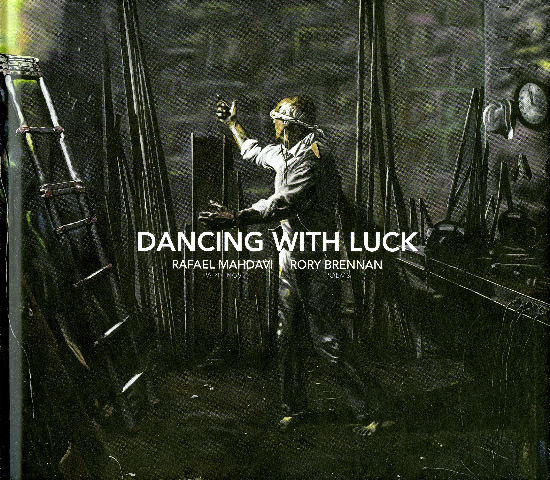

Rafael Mahdavi Dancing with Luck

Sonnets by Rory Brennan

By: Charles Giuliano - Jul 26, 2016

Dancing With Luck

Rafael Mahdavi Paintings, Rory Brennan, Poems

Essays by David Galloway and Jonathan Shimony

The American University of Paris

64 pages with nine illustrations, 2016

ISBN 9 782746 687271

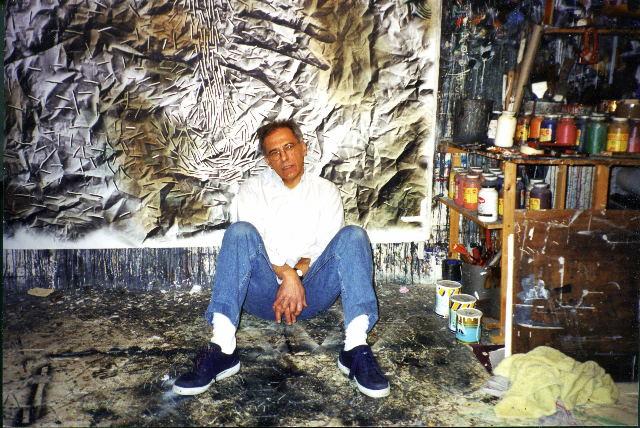

One of the pleasures for a critic is tracking the trajectory of an artist like Rafael Mahdavi over several decades.

Now 70, retired from teaching and living on a farm in the village of Chalmoux, in the Burgundy region of France, in 2015 he completed a series of nine painting.

These narrative works are more literal and descriptive than works we have shown and written about in the past.

Receiving the latest publication came with both surprises, thought provoking shifts, as well as elements that are deeply familiar.

There is the sense of shedding skin weathered by many decades of studio practice coupled with a clarity, focus and maturity based on a lifetime as father, teacher, thinker, writer, art historian and seer.

To engage with him at any level is to be involved with a lively, insightful, challenging critical process.

As a world traveler who mastered five languages while still in his twenties he has cut a wide swath. This has evolved into a direct, humor laden; take no prisoners persona in all matters pertaining to art and politics. He has utterly no patience for any form of bullshit including obscurantist art theories.

In this handsome and accessible book he states “At the start of the nineties, ideas that had been ricocheting in my mind for a number of years began to line up and make sense to me. Wittgenstein’s idea that language can only be public struck me as not only profound, but obvious. Private language is an oxymoron, as is the idea of personal and private painting. All communication is undermined by language, written, painted or in any other form. Any language has to refer to something other than itself. Painting about painting is as vapid as literature being about syntax and subjunctives, comas and so on. If painting is to communicate anything, is has to be about more than pigment, visual grammar and optics. Art needs to generate meaning, it is only worthwhile if it is shared, and it should leave people speechless…”

It is that kind of breathless communication with the masters that has informed his work through a lifetime of visiting great museums as temples and laboratory.

In the current teaching of studio art there is a disconnect with the past. There was a time when it was the norm for students to draw from plaster casts of classical sculptures or copy paintings in museums. One cloned the Old Masters in order to understand their process and poetic secrets.

This summer at the Clark Art Institute one of the delights of a show of nudes from the Prado was a Rubens copy of Titian’s “Rape of Europa.” It was insightful to see one master copying another. Although the works were not hung side-by-side in the memory bank of many encounters and prolonged contemplations of the Gardner Museum’s masterpiece there was the inevitable process of comparison.

Although the Rubens was a literal and faithful copy one wondered what he learned in the exercise. What was it about Titian, arguably the greatest painter of all time, that Rubens hoped to extract into his own work?

In a turning away from that approach theorists who dominate present day art academies might view this as labor intensive work and plagiarism. Manual dexterity has become anathema when compared to the freedom of conceptual art, a cult of originality, computer generated digital art and technologies.

Following the lead of Duchamp artists pride themselves in having little or no physical contact with their work.

For today’s mega-artists often the creator presides over a studio where the work is created in a factory environment by teams of assistants and technicians.

In this suite of nine paintings, working entirely alone, Mahdavi is old school. Just attempting to make non-traditional, representational, narrative paintings is an act of individuality and radical defiance.

It is a strategy that invites the indifference and scorn of the cynical contemporary art world. Mahdavi, as he comments in the text, invites recognition and respect by viewers in future generations when the current fashions and fevers have run their course.

Only then, perhaps, will art historians derive a critical niche for this progressive/ conservative work.

As one of his generation, five years his senior, I feel his quest for insight and mortality.

In the title work “Dancing With Luck” largely in grisaille we view the blindfolded artist in a position of torsion, barefoot, in what appears to be a workshop for fabricating sculptures. There is a crude, handmade ladder leaning against a wall seeming to ascend to a window and its play of light in the gloom.

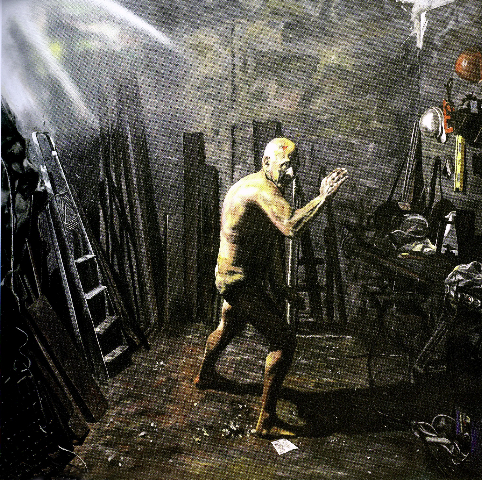

It made me think of a bleak and humorous play by Beckett, the master of the absurd, as I turned the page to “Fighting Sculptor.” Here the dramatically lit, nude artist, again in that dark workshop, has a posture that suggests Tai Chi. The body is both fit and reflective of age.

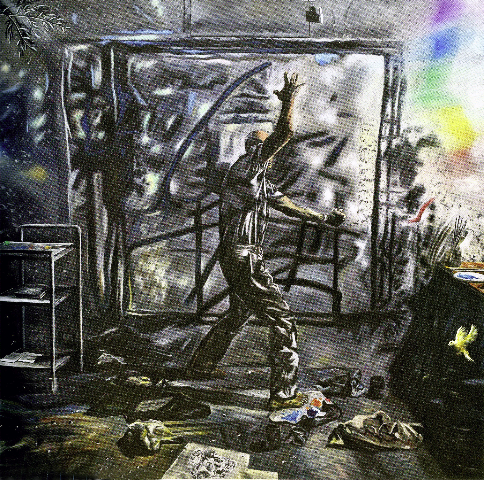

The intensity ratchets up to a gesture suggesting energy and emotion, perhaps anger or rage, certainly aggression in “Fighting Painter (Vanitas).” Now we are in his painting studio with a bird in flight in the lower right.

For many years the artist has employed a vocabulary of semiotics with metaphors attached to birds, dogs and other elements.

From these three self portraits the artist then explores the classical landscape of Claude and Poussin with “Picnic (Orpheus and Eurydice).” He evokes the legend of the underworld with two figures as small elements resting in nature.

Entirely unique and original is “Man on a Terrace.” It appears to be twilight, perhaps in Burgundy, as an owl in flight in the lower part of the canvas is illuminated by a bright ray of light. In a tree in the upper right of this twilight scene is a crow highlighted by a dim halo. There is a similar treatment of a sparse rose bush in the lower right corner. From the terrace the faintly described man stands and observes the metaphorical phenomena.

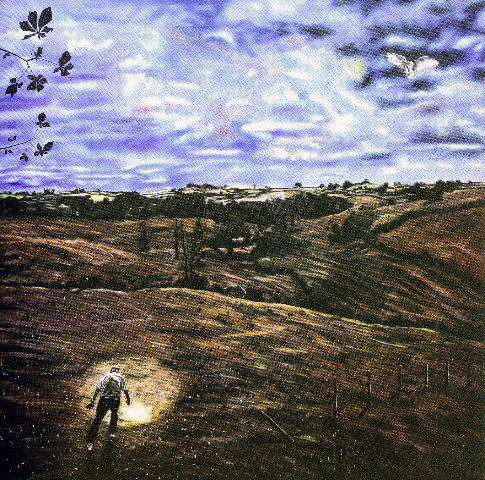

There is a sci-fi mood conveyed by “The Search.” Again there is subdued twilight in an expansive Burgundian landscape. In the foreground a man crouches moving forward cautiously. He is caught from above in a spotlight perhaps from a space ship. There are white flakes scattered about him suggesting unseasonal snow or dust. Other constant signifiers for the artist include the flying white owl and a collapsing fence.

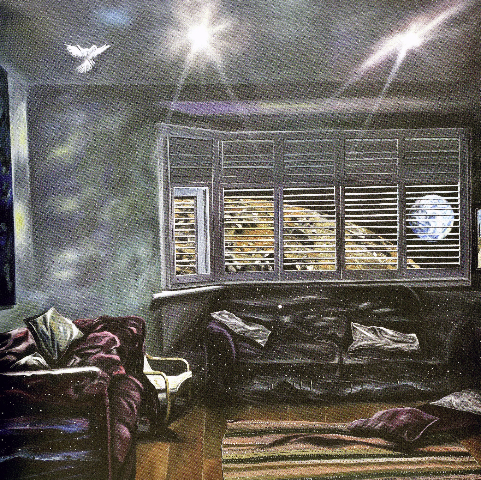

From exploring nature the artist depicts an interior. There is a generic living room with furniture and rugs in “Interior with Lunar Landscape.” Through venetian blinds we see the moon. Within the space is the owl as well as two flashes of ghostly light.

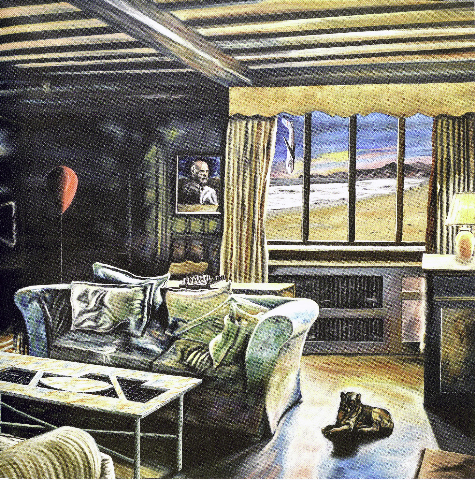

There is brighter more even illumination for “Interior with Plane Crashing.” There is a self portrait hanging next to the window with its view of a beach and distant mountains. In a disaster a large plane is plunging from the sky. On the floor, bathed in light from the window, a dog sits with seeming indifference to the disaster occurring outside.

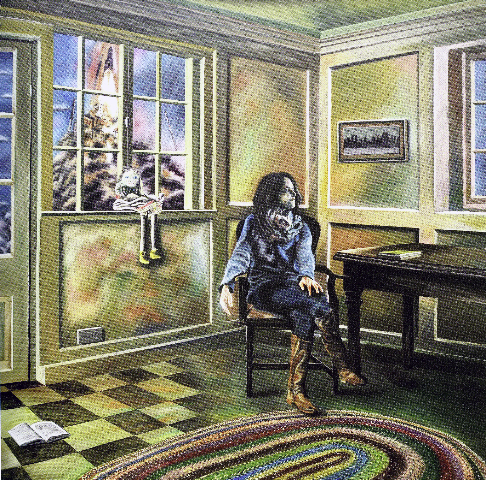

The final work in the series “The Writer” is both the most accessible yet confounding. Seated on a chair but turned away and distracted is his daughter Carter Ann. On the window sill is a memory of childhood represented by a seated rag doll. There is a book on the table next to the writer as well as one opened with an illustration on the checkerboard patterned floor.

This series of works was created as a suite and must be approached as a kind of visual parable conveyed in nine segments. We are encouraged to approach them as a whole and from that derive meaning, solace and insight.

We sense a burst of energy and commitment to create these works and collaborate with the poet and essayists. This beautiful book is complete unto itself. There is a satisfying sense of closure. But when recharged he will have more to say. Of this, knowing Rafael, we may be absolutely certain.