Zemlinsky at Bard: a Review

A Splendid evening of musical theater, not to be missed

By: Michael Miller - Jul 29, 2007

Alexander Zemlinsky (Vienna 1871 - Larchmont, NY 1942): Two One-Act OperasSung in German with English supertitles

A FLORENTINE TRAGEDY

(Eine Florentinische Tragödie)

Libretto by the composer, after the work of the same name by Oscar Wilde, translated by M. Meverfeld

Guido Bardi, Prince of Florence - Bryan Hymel

Simone, a merchant - James Johnson

Bianca, his wife - Deanne Meek

THE DWARF

(Der Zwerg)

Libretto by Georg Klaren, after Oscar Wilde's story "The Birthday of the Infanta"

American Symphony Orchestra,

conducted by Leon Botstein, music director

Directed by Olivier Tambosi

McDermott & McGough, set and costume designers

Robert Wierzel, lighting designer

Warren Adams, choreographer

The Dwarf - Jeffrey Dowd

Donna Clara, Infanta of Spain - Sarah Jane McMahon

Ghita, her favorite maid - Hanan Alattar

Don Estoban, the Chamberlain - Thomas Goerz

First Maid - Melissa Wegner

Second Maid - Maghan Stewart

Third Maid - Vanessa Conlin

First Playmate -Chanel Wood

Second Playmate - Julie Anne Miller

Sosnoff Theater, Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York

July 27, August 2 and 4 at 8 pm

July 29, August 5 at 3 pm

Opera Talk

With Leon Botstein

Sosnoff Theater

July 29 at 1:30 pm

Free and open to the public

I find myself torn between the temptation to write at length about these fascinating stage works by Zemlinsky and my responsibility to you, our readers, to let you know about this absolutely wonderful evening at the opera, so that you can grab some tickets before they all disappear. Yes, this will have to be short, and it cannot do justice to these brilliant operas or the amazing work all of those involved have put into these splendid productions. The experience was both profound and immensely entertaining.

We owe this first of all to Alexander von Zemlinsky's dramatic genius. Primarily a pit conductor since he became the first Kapellmeister of the new Vienna Volksoper* in 1906 at the age of thirty-five, he seems to have had the theater in his blood. He wrote both A Florentine Tragedy (1917) and The Dwarf (1922) during his 16-year tenure as music director of the Deutsches Landestheater in Prague from 1911 to 1927. In these brief, densely concentrated works, his sense of timing and dramatic effect are unerring, as well as his ability to juggle sardonic humor and the tragic. Whatever else they may be, these two one-acters make for a great show.

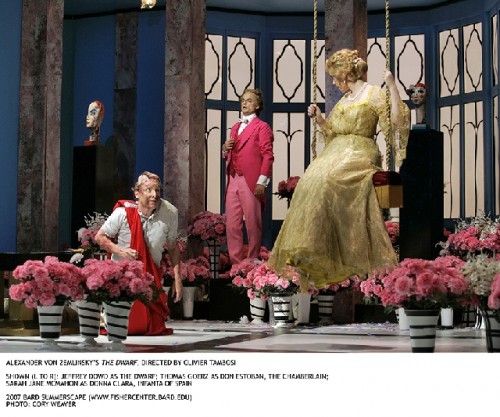

The rest of the credit can be shared by Leon Botstein's flexible and lively conducting, the committed and excellent playing of the American Symphony Orchestra, Olivier Tambosi's penetrating direction, McDermott & McGough's set design, Warren Adams' choreography, and the performances of an extraordinarily versatile cast, especially the tours de force of the great James Johnson as Simone in A Florentine Tragedy, and Sarah Jane McMahon as the Infanta, Donna Clara, in The Dwarf, not to mention Jeffrey Dowd's deeply humane and moving performance as the dwarf.

The photographs I reproduced in my preview did not make it clear that the contemporary-looking, predominantly white set for A Florentine Tragedy is in fact a shadow box raised some five feet from the stage floor. Representing the rich cloth merchant's salone, it is by no means small, but the converging surfaces of the walls, floor, and ceiling exaggerate perspective, and, paradoxically, give the room a claustrophobic feeling, a perfect emblem of Wilde's lines, literally translated in Meverfeld's libretto:

SIMONE. ...Is all this mighty world

Narrowed into the confines of this room

With but three souls for poor inhabitants?

Ay! there are times when the great universe,

Like cloth in some unskilful dyer's vat,

Shrivels into a handbreadth, and perchance

That time is now! Well! let that time be now.

Let this mean room be as that mighty stage

Whereon kings die, and our ignoble lives

Become the stakes God plays for.

Narrowed into the confines of this room

With but three souls for poor inhabitants?

Ay! there are times when the great universe,

Like cloth in some unskilful dyer's vat,

Shrivels into a handbreadth, and perchance

That time is now! Well! let that time be now.

Let this mean room be as that mighty stage

Whereon kings die, and our ignoble lives

Become the stakes God plays for.

James Johnson, a man of impressive physical presence himself, appears like a menacing giant, a deformed monster of a sort, when he moves to stage rear, where the main door to the apartment stands. His performance as Simone is the very model of operatic singing acting at its very best. In total vocal, intellectual, and physical command of the character—like the others an extremely unpleasant one—he affects us as a dangerous human animal, caged until he fully realizes the situation, comes to terms with it, and throws himself into action, insofar as he is a free agent or an instrument of fate—themes amply developed in the libretto, which is, as far as I can tell at this point, is a straightforward translation of Wilde's original fragmentary play—unlike The Dwarf, but more of that later. Bryan Hymel has a big, bright tenor voice, almost too robust for the languid écornifleur Guido, who lounges about Simone's salone, as if sex with his wife Bianca and taunting the cuckold were more or less equally entertaining ways of passing empty time, but he managed his instrument well and shaped his line in a most musicianly way. Deanne Meek also sang beautifully, and effectively projected her changing emotions with voice and body as she steered her course—at first wrapped in a sheet, then silver brocade, and finally the red evening dress she took off before the curtain rose—in the power struggle between the two men, her spoiled aristocratic lover and her detested husband, who views her as mindless, ordinary chattel. Although all three parts are psychologically developed, and each has his or her set piece to sing, Simone's is by far the largest role, and in places he appears to carry the opera by himself, with the other two almost as his satellites. This comes across as an interesting idiosyncrasy of Zemlinsky's writing in both operas, and not as a fault. As the short, tense work unfolds, the characters appear more balanced on a conceptual level, as if Simone and Guido represented two opposing male behaviors in relation to a desirable woman. Zemlinsky's insight into masculine behavior is such that can only come from an outsider, in his case stemming from his small stature and ugliness. These shortcomings contributed to the failure of his relationship with Alma Schindler, later the wife of Gustav Mahler and others, a wound which came to full fruition over twenty years after the event in The Dwarf. In fact she referred to Zemlinsky as "her little dwarf."

The only real criticism I would make of the production are the points at which Tambosi chooses to side-step actions described in the text. Of course theatrical license is necessary and desirable in the real world of the stage, but it is irritating to see Bianca pointlessly lighting candles in the salone, when Simone calls for a torch to light Guido's way down the dark staircase outside, or to hear Simone talking of an array of precious fabrics and none of them appear to accompany the described action, etc., etc. It's just a matter of what you can get away with, but Tambosi should not assume that no one in the audience follows the text, particularly now that we have supertitles. On the other hand, Tambosi responds to text and music at many different levels, showing his impressive intelligence as a director.

The double-bill most impressively shows the range of Zemlinsky's dramaturgy. It seems unfair to call The Dwarf, a longer work, a more substantial one, but it is undeniable that it covers a vast range of human experience, morality, and emotion. It is quite amazing what Zemlinsky was able to condense into barely two hours. Also, his approach to his Wildean model, in this case a prose fairy-tale, was entirely different. The libretto is a free adaptation by Georg C. Klaren, who only a few years later began a successful career as a screenwriter and director. (He filmed a highly regarded film version of Büchner's Woyzeck in 1947. Where are you KINO INTERNATIONAL?) In fact there is something presciently cinematic about his treatment of the monster who doesn't understand that he is a monster, an important topos in German expressionist film and its tributaries—and not only in the horror genre. In any case Klaren's libretto differs in many ways from its model: the Infanta is not celebrating her twelfth birthday, but her eighteenth. The dwarf is a singer more than a dancer. In his festive robes and sash, playing the lyre, he recalls Tannhäuser, and of course Zemlinsky himself. He was not found by chance in the forest; he is an exotic gift from the Sultan, early separated from his family by the Spaniard who captured him and kept him enslaved aboard a ship for ten years, wandering about the globe. The range of the dwarf's deluded consciousness is vast, encompassing poetic lyricism, a heroic experience of the world, and a universal imagination. Zemlinsky give us hints of Siegfried and Parsifal in the dwarf's innocence. (And I must apologize for summarizing Wilde's story, not the opera, in my preview article.) Of course the true horror of the story is the callousness and solipsism of the Infanta, heightened by her maid Ghita's humanity, but we experience the peripeteia of this real tragedy through the dwarf's horror, as he looks at himself in the mirror and realizes that what he sees is not the ghostly Doppelgänger he saw at sea, but himself.

More than in their design for A Florentine Tragedy, McDermott & McGough put the Belle Époque at the center of their concept for The Dwarf, with hints of the 16th century and the present. The art deco set is not only a palace in 16th century Spain, but a sumptuous Weimar era residence and a Park Avenue duplex rolled into one. Tambosi is to be thanked for not carrying this contemporary allusion further, not that Park Avenue isn't rife with little princes and princesses who could fit into Donna Clara's shoes quite comfortably. The production of this complex work is right on the mark throughout, touching the just combination of the operetta and Richard Strauss at the beginning, encrusting its later pathos in fierce irony.

Sarah Jane McMahon not only manages her lovely soprano voice to perfection in her portrayal of the Infanta, her virtuosic command of movement is extraordinary. Tambosi makes full use of this aspect of dramatic art throughout the production, making huge demands on his cast. It was a brilliant idea to cast Jeffrey Dowd as the dwarf; his dark timbre and the rich center of his tenor voice are able to bring across the heroic side of the dwarf, as well as his lyrical gifts as a singer. His acting in the huge emotional range of the part was most moving. Hanan Alattar sang attractively and gave a most humane impression in the important part of Ghita, "who would make all joyless and ugly people happy with [her] love." Thomas Goerz sang impeccably, holding up the farcical side of the story as Don Estoban, the Chamberlain.

Leon Botstein and the American Symphony Orchestra gave an energetic and nuanced performance of Zemlinsky's rich but transparent scores. The flexibility he gave to the composer's expressive, often meltingly beautiful lines, and the space he gave to his textures (thanks to the superb hall acoustics) were especially gratifying.

This discussion only scratches the surface of these rich and eminently stage-worthy operas. As accessible as they are on many different levels, including pure entertainment, it is truly astonishing that they are not firmly ensconced in the repertory. Of course they are at their best on an intimate stage like that of Sosnoff Auditorium...not a common feature of the American operatic world.

As Don Escobar would say, "Get moving! The sun isn't standing still!" Better call the box office now.

---

*Both Tosca and Salome, a crucial model for Zemlinsky, received their Vienna debuts there.

---

Web: http://homepages.nyu.edu/~mjm11/index.html

E-mail: heliagoras@gmail.com