Supernatural Wife at Jacob's Pillow

U.S. Premire by Big Dance Theatre

By: Charles Giuliano - Aug 01, 2011

Supernatural Wife (2011)

Based on Alkestis by Euripides

Translated by Ann Carson

Directed by Annie-B Parson and Paul Lazar

Choreography by Annie-B Parson and Paul Lazar

Set Design, Joanne Howard; Lighting Design, Joe Levasseur; Sound Design, Jane Shaw; Video Design, Jeff Larson; Costume Design, Oana Botez-Ban; Music, Men by David Lang (2001) performed by Mike Svoboda and Jurgen Grozinger; Choral/Vocal Music, Chris Giarmo; Text in Silent Film, Rainer Maria Rilke.

Performers: Molly Hickok (King Admetus), Tymberly Canale (Alkestis), Chris Giarmo (Servant), Elizabeth DeMent (Maid), Aaron Mattocks (Thanatos), Peter Simpson (Apollo/ Heracles). Additional Performers in Film, Paul Lazar and Hope Hickok; Child’s Voice, Simon Eskin.

Big Dance Theatre

Jacob’s Pillow

Doris Duke Theatre

July 27 to 31, 2011

Long before the start of the play, King Admetus was granted by the Fates the privilege of living past the allotted time of his death. The Fates were persuaded to allow this by the god Apollo (who got them drunk). This unusual bargain was struck after Apollo was exiled from Olympus for nine years and spent the time in the service of the Thessalian king, a man renowned for his hospitality who treated Apollo well. Apollo wishes to repay Admetus' hospitality and offers him freedom from death. The gift, however, comes with a price: Admetus must find someone to take his place when Death comes to claim him.

The time of Admetus' death comes and he still has not found a willing substitute. His father, Pheres, is unwilling to step in and thinks that it is ludicrous that he should be asked to give up the life he enjoys so much as part of this strange deal. Finally, Admetus' devoted wife Alcestis agrees to be taken in his place because she wishes not to leave her children fatherless or be bereft of her lover. At the start of the play, she is close to death.

Wow.

Fresh. Inventive. Vibrant. Multivalent.

Although The Supernatural Wife, based on the Greek tragedy Alkestis by Euripides, was given its U.S. premiere, by Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, the multi media Big Dance Theatre has stretched to the snapping point our definition of dance.

So much so that a group of seniors exiting the theatre were conducting an informal audience survey. An older gentleman was quite put off. He had come to Pillow expecting tutus. In this production that included spoken text, video projections, microphones, chanting and song, as well as Heracles bashing away at a drum kit, this was hardly Swan Lake.

The woman we spoke with assumed that younger members of the audience enjoyed it more than seniors. As fellow seniors she was surprised when Astrid and I informed her that we had loved the production.

It was, in fact, precisely what one hopes and expects to find at Jacob’s Pillow. The programming includes established companies and the classical/ modernist tradition, world dance, as well as experimental groups like Big Dance Theatre.

Truly, Supernatural Wife proved to be one of the most challenging and enjoyable evenings of theatre we have experienced this season. Note that I have evoked the broader term Theatre rather than Dance. Because that is exactly what it was- a totally theatrical phenomenon- evoking the full arsenal of aesthetic possibilities.

In a pre performance lecture, which proved very helpful, we were informed that the company was indeed returning to the classical Greek traditions which combined music and dance with drama. Euripides, in particular, was noted for introducing elements of ironic humor to tragic themes. This is a vein that the company minded most effectively. There were indeed unexpectedly hilarious moments but they never tipped the balance of the solemnity of the plot.

It also appears that among the reasons that the dramas of Euripides have proved to be enduring, this play was first performed in 438 B.C.E., is that he was concerned with exploring relationships and the role of women.

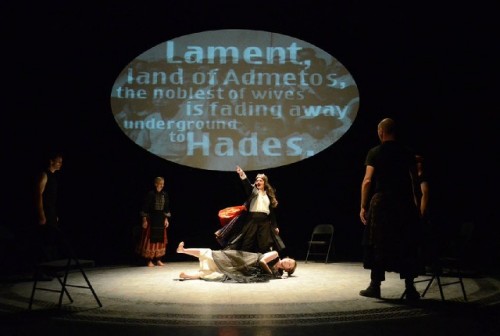

In this case Alkestis, as poignantly performed by Tymberly Canale, through her sacrifice, is more compelling and noble than her husband, King Admetus (Molly Hickok), for whom she has exchanged her life.

The contrast is sharpened by rendering King Admetus as a comic character. He is performed by a woman who in a bit of theatrical legerdemain, first pops up from a bit of red curtain as a man with a crown, disappears for a moment and reappears with a silly pasted on moustache. For the rest of the performance, not all that convincingly as intended, Hickok banters about with broadly manly gestures. We know of course that he is anything but and the production informs us that in accepting the sacrifice of his wife Admetus is indeed less than a man.

Perhaps he might look like a man, a drag king of sorts, but the joke is that he lacks stones.

In a kind of spoofy play on reality vs theatre there is an interesting device of introducing characters by microphone identifying them with stage directions.

A parody within the parody for example might be “Critic enters stage left, observes action, and writes review.”

It was a compelling and delightful evening of such riffs. Like Heracles the galvanic drummer. Good grief. But here Pete Simpson deports himself with gusto. Then in a Heracles spoof that cracked up the audience he hoisted a large drum on his shoulder, as though it weighed a ton, and announced that he must be off to perform other tasks.

Heracles, a demi god who regularly enjoys the famous hospitality of King Admetus, must perform seven labors in order to be welcomed into the pantheon of Mt. Olympus. Wrestling with Thanatos (wonderfully played by the grim Aaron Mattocks) is just a sidebar and not one of his status earning labors.

What is most impressive about this company is its range of assets. A primary focus is dance and movement. Then add to that dramatic readings, singing, and multi media projections.

The work started with ensemble dance. First individually and then adding on layers until all six performers were synchronized with identical steps that channeled traditional Greek folk dance, as well as hip hop and disco moves, including stomps with elaborate hand and arm movements. The sound track of loud, rock/ electronic music conflated with what one sees in elaborately staged rock acts like Lady Gaga. One signifier is that they wore black, lace up boots for a paramilitary accent. This was a further demarcation from the norm of contemporary dance.

During this initial dance sequence one had little sense of where this configured into the narrative based on Euripides. The identities of the players were revealed to us gradually. For example Hickok, who is first revealed to us as clearly a long haired woman, with the addition of two props- a crown and moustache- transformed into King Admetus.

Through an addition of a long white gown over more generic gear Canale became Alkestis. Her dancing, solos and a stunning duet with Heracles, were riveting. The frenetic anguished movement evoked the condemned maiden and her famous spastic solo in Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps.

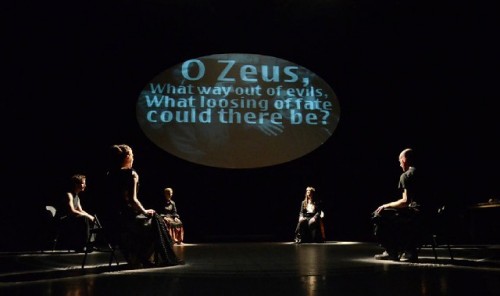

As the narrative advanced it was interspersed with varying vignettes. It was effective when the company sat in a circle and chanted/ sang the text which was simultaneous projected. The combination of reading and hearing made us completely absorbed. Unlike the hypertext of an opera the text was designed in a compellingly graphic manner that entirely enhanced the experience.

The use of film and video projection was always remarkable. We wondered why we were viewing scenes of Greta Garbo and how that conflated with Euripides. There was a constant element of surprise and invention.

The condemned Alkestis expresses concerns that her husband will find another woman to share his bed and be mother to her children. Two television monitors are wheeled onto the stage with images of a child accompanied by a plaintive voice. It was an example of the constantly clever manner of accenting narrative points.

We were never allowed to suspend the boundary between theatre and reality. There was both respect for the integrity of the text as well as playful spoofs. Now and then a character would utter a word or line such as “gotcha.” We smiled as we instantly connected the arc between the ancient and contemporary world.

The evening deconstructed the ancient play. Its inventive, and at times humorous manner, all the more made us consider the essence of its tale of loss and sacrifice. The heroic and giving gift of her own life by Alkestis and the selfishness and arrogance of King Admetus in allowing her death to transpire.

Through his friend Heracles King Admetus is given back his wife. Conventional wisdom today would conclude that he does not deserve her. Which is, perhaps, why the production opted to emphasize her classical elegance, and render him as a caricature and fool.

The fabulous performance by the inventive Big Dance Theatre proved to be richly entertaining as well as deeply thought provoking.