Rethinking Turgenev’s A Month in the Country at Williamstown

New Concept and Translation Directed by Richard Nelson

By: Charles Giuliano - Aug 03, 2012

A Month in the Country

Ivan Turgenev

Translated by Richard Nelson, Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky

Directed by Richard Nelson

Scenic Design, Takeshi Kata; Costume Design, Susan Hilferty; Lighting Design, Japhy Weidman; Sound Design, Drew Levy; Production Stage Manager, Eileen Ryan Kelly; Production Manager, Eric Nottke; Casting Calleri Casting

Cast: Louis Cancelmi (Arkady Islaev), Jessica Collins (Natalya), Parker Bell-Devaney (Kolya), Charlotte Bydwell (Vera), Kate Kearney-Patch (Anna), Elisabeth Waterson (Lizaveta), Jeremy Strong (Mikhail Rakitin), Julian Cihi (Alexi Belyaev), Paul Anthony McGrane (Afanasy Bolshinstov), Sean Cullen (Ignaty Shpigelsky) Harry Ford (Matvei).

Williamstown Theatre Festival

Main Stage

August 1-19, 2012

For the Williamstown Theatre Festival there was a formidable risk factor in programming Ivan Turgenev’s A Month in the Country (written 1848-50 and published in 1855) as its third and final Main Stage production for the 2012 season.

There was logic to opening with a comedy, a Damon Runyon inspired take on Oscar Wilde’s popular The Importance of Being Earnest. It had the marquee, star power of David Hyde Pierce, with his second try as director, and Tyne Daly in a key role. That was followed by a workshopped musical. In this case a roll of the dice setting a soapy 1950s inspired film Far From Heaven to music. Then finishing with a drama. Comedy, musical, drama. That makes sense.

A safer bet for the anchor slot would have been to move a sold out run of Elephant Man with Bradley Cooper and Patricia Clarkson from the smaller Nikos Stage to the larger Main Stage.

An experimental production of A Month in the Country, hardly a crowd pleaser, particularly with a cast of young and unknown actors, was a long shot to make its nut on the Main Stage.

In order to achieve a sense of intimacy the director, Richard Nelson, who worked with translators Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky to create a new script, opted to remove the first three rows (42 choice orchestra seats) to extend a thrust stage. The proscenium stage was for the most part bare except for a fire curtain which was raised and lowered a tad between scenes. There was also a curtained line across the stage fluttering with a soft breeze signifying nature. The play is set, may we remind you, in the country. We also heard the occasional bird.

The action, if that is the right term for a play more about mind games and intimate conversations than plot points, takes place on the thrust. Between scenes the actors changed some items of furniture suggesting rooms or a bench in nature. When not involved in the dialogue they sat on chairs and observed.

All that minimalism and intimacy, it would seem, would have worked quite well in Nikos.

Why then put it on the Main Stage?

Simple.

First, may we remind you that this is the Williamstown Theatre Festival? After some years in the wilderness, another story, this season WTF has regained its historical status as one of the nation’s foremost, regional, non profit theatre companies.

This stunning, challenging, radical new production of a true monument of theatrical modernism is a really big deal. We are truly astonished by its authenticity, respect for the past, innovation, and flawless technical execution.

Ok. Sure. The first act was a bit of a slog. There was a period of adjustment to so many radical elements from staging, set design, sound, lighting and the deliberately understated naturalism/ non acting of the actors.

Also, even though Nelson was working with a refreshed text that falls easily on an American ear, this is, after all, for cripes sake, a Russian play! Which is to say that the characters talk and talk and talk about feelings and agonizingly, repressed, stylized emotions.

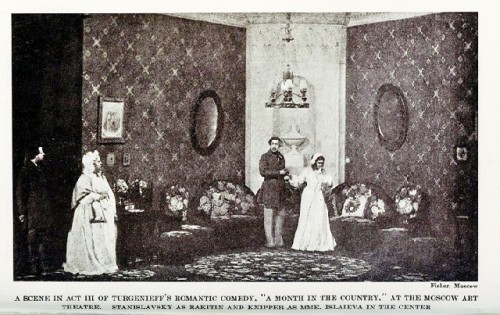

If you like Chekhov, not everyone does, then this is Chekhov to the max. More so. Turgenev, and this play in particular, was the source of inspiration for all things Chekhovian. In fact Chekhov convinced Stanislavsky to produce A Month in the Country (it had been banned).

It was Nelson’s insight and inspiration that Month in the Country suffered from bad translations and miscasting of the key role of Natalya as a woman in her fifties smitten by the tutor, Alexi Belyaev, a student in his early twenties. It becomes a very different play when Natalya (Jessica Collins) is cast, according to the playwright’s intentions, as about to celebrate her 30th birthday.

Through research Nelson learned that Stanislavsky’s approach to the play introduced The Method as well as a nascent approach of minimalism in staging and set design. Nelson’s intention was to restore the play with its innovations intact and to employ the craft and technical resources of contemporary theatre. This embodied a system of many microphones with a sound board mixing and amplifying the tones and direction of seemingly normal discourse.

During an extended press conference Nelson discussed his radical concepts. Of course there is a difference between theory and practice. Would this prove to be an archival, academic project? How would it play to a live audience?

Yes, initially, there was steep learning curve. Nelson had talked about looking through a peephole or over the shoulder at conversation. We discovered what that meant. During scenes we were staring at an actor’s back although we could hear every word of dialogue. Facial expressions and body language were non factors.

With no sets, few if any props, a few pieces of furniture, here and there a bit of sound, or that fluttering curtained background, the emphasis was entirely on dialogue and that oh so subdued “acting.” The options were to tune in and focus on the undulating, subtle, ebb and flow of those endless, psychologically tense dialogues, or just zone out fluttering off into space.

A huge credit for the success of this production rests on the extraordinary and mature beyond her years performance by Collins as Natalya. Just last week we had experienced Patricia Clarkson as Mrs. Kendal in Elephant Man. It is the benchmark of a female, dramatic role of the Berkshire season thus far. Some critics rated it the performance of the decade. That said, keep an eye on Jessica Collins. She was the glue that held together a far more challenging role in a much more difficult play.

It is really her story and speaks to broad and complex issues. The norm of a woman of her status, the inheritor of a large estate, was to marry on her social and economic level. In this case, she was the heiress who made a sensible marriage. Love was not a factor in these matches. Accordingly, spouses were free to pursue romantic interests outside of marriage once heirs were produced. She has a son Kolya (Parker Bell-Devaney) for whom a tutor has been hired for the summer.

Even adultery was tolerated if pursued with discretion. It is the rule which Anna Karenina violated with tragic consequences in Count Leo Tolstoy’s epic novel (1875-1877). Of course there was a double standard as men frequented brothels or kept mistresses. Some courtesans achieved notable wealth and social status.

There was endemic hypocrisy about the sanctity of womanhood. It is the theme that dominates A Month in the Country.

Mikhail Rakitin (Jeremy Strong) a friend of Natalya has arrived for his annual visit. Although they declare their “platonic” love he was passed over as a suitor for the better, but arid match with Arkady Islaev (Louis Cancelmi).

The scenes in the first act between Mikhail and Natalya were so understated that it was difficult to become absorbed by them. Was this about Strong’s uncharismatic acting or was he indeed being true to the ineffectual, meek and colorless character? This became more apparent when Natalya behaved quite differently when infatuated on first sight by the guileless, innocent, scrumptious tutor, Alexei, played with natural charm and riveting brilliance by Julian Cihi.

Folded into the mix of a focus on Natalya are two other love interests. She is responsible for her now seventeen-year-old ward Vera played by Charlotte Bydwell. Of course Vera is smitten with Alexi who is the right age but a potential husband with no assets. Dr. Ignaty Shpigelsky, initially overplayed by Sean Cullen, has a suitable but boring, rich, older suitor in Afanasy Bolshinstov (Paul Anthony McGrane). As matchmaker, Dr. Shpigelsky stands to be rewarded with a fine troika.

It took patience to absorb the complex, wordy exposition and stark style of the first act. When we returned to our seats, however, I was hanging on every word. Collins, balancing her “friend” Mikhail, boy toy, Alexei, rivalry with Vera, and husband Afanasy, went through so many mood swings that we were quite dizzy before it all wound down.

Go. Stay. No leave. Come back. OMG. Drama morphed into ironic comedy. Like, well, Chekhov.

It was all quite delightful.

A major transition in the second act was the development of Dr. Shpigelsky. Initially his projecting, as actors are supposed to do, seemed out of sync with the low key naturalism of this amplified production. Perhaps, as a more mature actor, it was more difficult to adjust to Nelson’s approach. But during a scene in which he proposes to Lizaveta (Elisabeth Waterson) he is hilariously disarming in frankly stating his mediocrity. He confesses to being a terrible doctor who will not treat her should she fall ill. Asked for her age she lies then admits to being 36. The humor of his proposal entails marriage as a default arrangement. It’s what many marriages become but not from bended knee.

There is a fascinating confrontation between Natalya and Vera. She is a ward not daughter and heir. As such she is poor with no dowry. Natalya tantalizes her asking, doesn’t she want her own home, and to be free from dependency? Of course that’s not likely with Alexei. Finding it now impossible to remain under Natalya’s roof Vera accepts the safe proposal of Afanasy.

The end is rather dismal. Both Mikhail and Alexei, men of principle, opt to leave. Natalya is left with her boring husband and sterile marriage. She has outplayed herself. Alexei, through no fault of his own, reflects that he is unsuited to “Turning the heads of girls and rich older women.” Dr. Shpigelsky offers to drive him to the train station in his new troika.

Perhaps the play and Nelson’s ambitious production set the bar too high. The degree of difficulty is beyond the grasp of most audiences and critics. But I feel the better for having endured the experience. It is an evening of theatre that lingers, perhaps for a lifetime. Surely, it is a production I will never forget.