Rodin in the United States: Confronting the Modern

Blockbuster Exhibtion at Clark Art Instutute.

By: Charles Giuliano - Aug 09, 2022

Rodin in the United States: Confronting the Modern

Clark Art Institute

Williamstown, Mass.

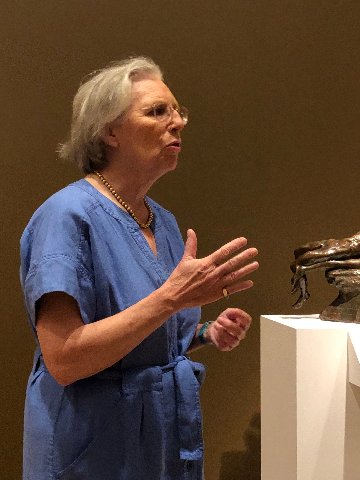

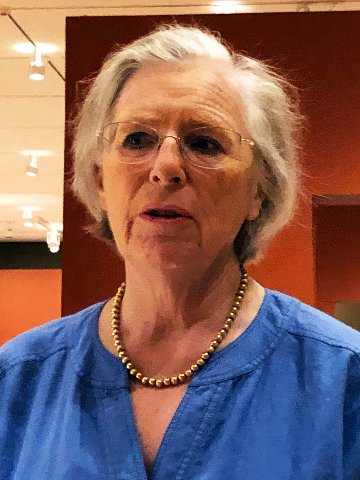

Curated by Antoinette Le Normand-Romain with the collaboration of Christina Buley-Uribe, an expert on Rodin’s drawings. The Clark’s curatorial team, includes Esther Bell, Robert and Martha Berman Lipp Chief Curator, Alexis Goodin, curatorial research associate, and Kathleen Morris, Sylvia and Leonard Marx Director of Collections and Exhibitions.

Through September 18

François Auguste René Rodin (12 November 1840 - 17 November 1917), known as Auguste Rodin, is regarded as the leading sculptor of the fin de siecle in France. In the beginning there were obstacles to overcome. He was in his mid thirties when he began to gain recognition, most notably, through controversy in the United States.

He was rejected three times by École des Beaux-Arts. The primary task of this leading institution was to train painters and sculptors to execute government commissions. The academic program of rigorous training sustained the neo classicism of Jacques Louis David and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. The foremost sculptor of the time was Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux.

He matriculated to Petite École which he left in 1857. It was an academy for the decorative arts and plaster works of architectural ornamentations. There he studies with and admired Carpeaux but later derived a radical style that, like the pioneering impressionists, led to rejection by the annual official salons.

After initial training he earned a living as a craftsman and ornamenter for most of the next two decades, producing decorative objects and architectural embellishments. He took classes with the animal sculptor Antoine-Louis Barye. He entered the studio of Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse, a successful mass producer of objets d'art. He worked as his chief assistant until 1870, designing roof decorations and staircase and doorway embellishments.

In 1864, Rodin began to live with Rose Beuret (born in June 1844). As the artist became more successful there were many affairs. The most complex was with a studio assistant Camille Rosalie Claudel (1864-1943). The exact nature of their relationship is the subject of interest and much research. She has been described as a collaborator and muse. Claudel demanded that he abandon Beuret which he refused to do.

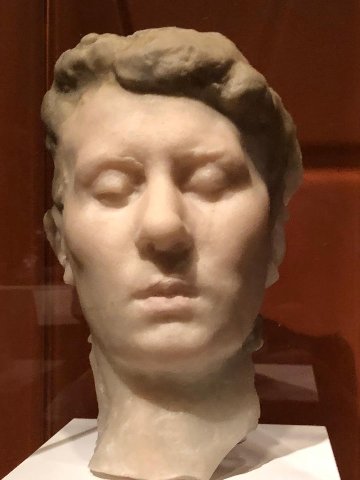

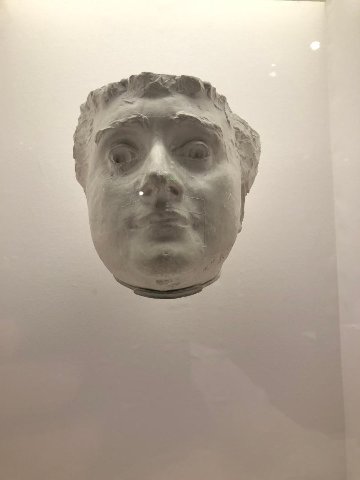

The exhibition at the Clark, Rodin in the United States: Confronting the Modern has works related to the women which may well not attract much attention from visitors. At the end of their lives he married Beuret by whom they had a son. There is a poignant soft, glowing head of her created in the melted glass or pâte de verre process. The exhibition includes Claudel’s bronze portrait of Rodin which, at the very least, reflects his style and influence.

While working with other artists he applied for government commissions and to the Salon without success. Even when commissions did later come they proved to be problematic.

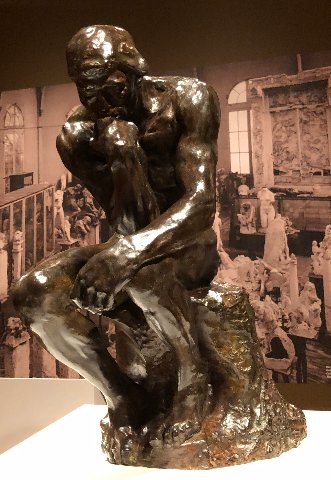

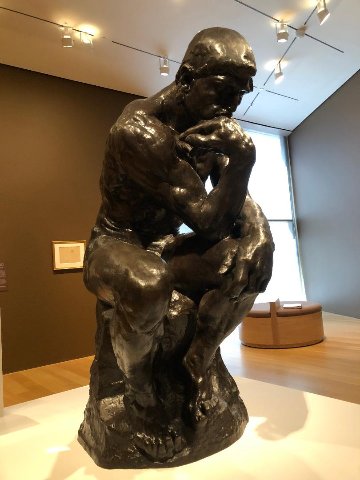

He won the 1880 commission to create a portal for a planned museum of decorative arts. The government commission came with a studio. Rodin dedicated much of the next four decades to his elaborate Gates of Hell, an unfinished portal for a museum that was never built. Many of the portal's figures became sculptures in themselves, including Rodin's most famous, The Thinker and The Kiss. The Clark displays two versions of The Thinker and one of The Kiss.

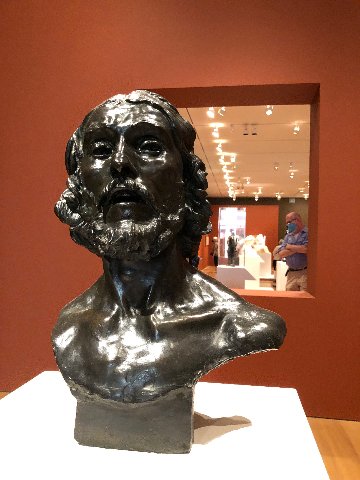

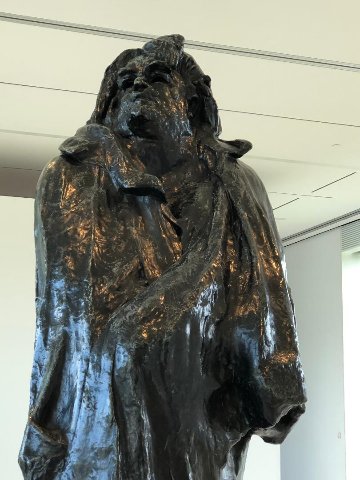

The Burghers of Calais entails twelve original castings and numerous copies. It commemorates an event during the Hundred Years' War, when Calais, a French port on the English Channel, surrendered to the English after an eleven-month siege. The city commissioned Rodin to create the sculpture in 1884 and the work was completed in 1889. There is a colossal bronze head of Pierre de Wissant, one of the burghers, on display.

In honor of the French novelist Honoré de Balzac a work was commissioned in 1891 by the Société des Gens de Lettres. A full-size plaster model displayed in 1898 was rejected by the société and Rodin moved it to his home in Meudon. On 2 July 1939 (22 years after the sculptor's death) the model was cast in bronze for the first time and placed on the Boulevard du Montparnasse at the intersection with Boulevard Raspail.

For this commission Rodin read Balzac in depth and made numerous studies. That culminated in a radical decision to depict the writer (in fact short and fat) at monumental scale wrapped in a cloak with a head that was less than a likeness and more of an interpretation of the writer.

After his death, in subsequent decades, the reputation of Rodin was in decline. In 1954, Alfred Barr, director of the Museum of Modern Art, requested a bronze cast of Rodin’s Monument to Balzac for the museum’s collection. Barr considered Balzac one of the greatest sculptures in the history of Western art. From that moment, scholars and critics began a reappraisal.

A version of that work, as well as studies, are part of the Clark exhibition. You encounter the monumental piece in its own gallery just to the right as one enters the museum. The enormous and imposing work has been given plenty of breathing room.

This contrasts with the density of 50 sculptures which range in scale from monumental to studies and fragments, as well as, 25 drawings in the basement special exhibition galleries.

This judicious selection, drawn entirely from American collections, entails a generous encounter with the renowned sculptor.

The exhibition’s curator, Antoinette Le Normand-Romain, the author of Rodin’s catalogue raisonné, insists that this is not just another retrospective. The installation and catalogue have the scholarly mandate of laying out the complex and fascinating saga of how, in essence, Rodin conquered America after an initial rough start.

When the artist finally exhibited his work it was a display of plaster casts. Clients could purchase works in bronze and marble. Neither of which were executed by the artist. Rodin was a master of the additive technique of modeling in clay. Which was then cast in plaster or fired as terra cotta.

The marbles are generally unique and created with the pointing technique of precise measurements from the original. To make a bronze piece molds are created from the original plasters. Theoretically, an unlimited number of sculptures can be created from the original molds.

When he left his estate to the government and the eventual Rodin Museum he authorized posthumous production. This was intended to support and sustain the museum. The French passed legislation setting a limit of 12 copies which would be regarded as authentic or original. Some of Rodin’s original casts have been used commercially.

Scholars like Rosalind Krauss have argued that anything not approved by the artist is a fake or forgery. Other argue that today's techniques are in fact equal or superior to those of the artist's lifetime.

It is this proliferation of bronzes, during and after the artist’s lifetime, that created the possibility of so much work in American museums and private collections.

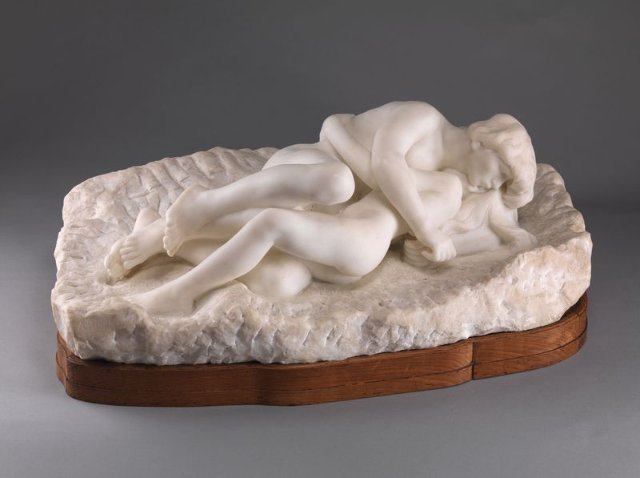

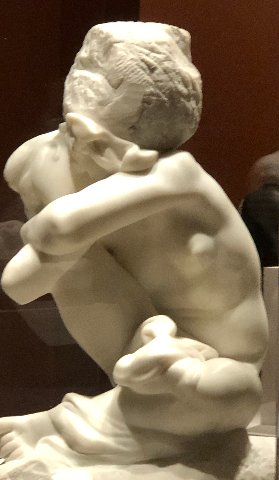

The first group of his sculptures was shown in the United States at the Centennial International Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876 and went largely unnoticed. Sara Tyson Hallowell (1846-1924), developed the “Foreign Masterpieces Owned in the United States” exhibition for the Department of Fine Arts at the 1893 Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition. That entailed three Rodin marbles, including Cupid and Psyche (before 1883), to be shown in the Fine Arts Building at the international fair. They were judged too provocative and moved to a restricted space.

As was so often the case with modern art the succès de scandale attracted media attention and collectors. Samuel Isham acquired the marble, Fallen Caryatid, now in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts and on view at the Clark. In 1893 Samuel P. Avery gifted The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bust of Saint John the Baptist (1888). It was the first work by Rodin to enter an American museum. By 1912 the Met opened its Rodin gallery and owns some 100 plus works.

During the media tour the curator, Le Normand-Romain, expressed dismay that the Met, which loaned small studies, was not more generous. "They have a hundred works, " she said.

The high relief carving of Cupid and Psyche, on its original wooden base, is the centerpiece of the Clark exhibition and cover illustration for the catalogue. If it is emblematic to his opposition in America he also had his battles in France.

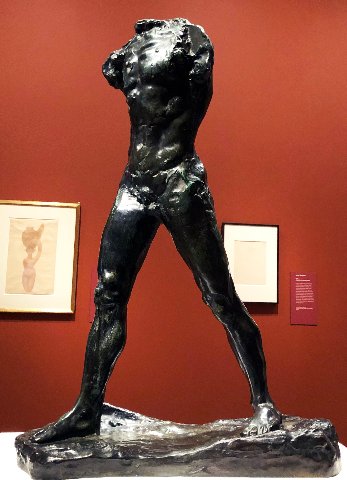

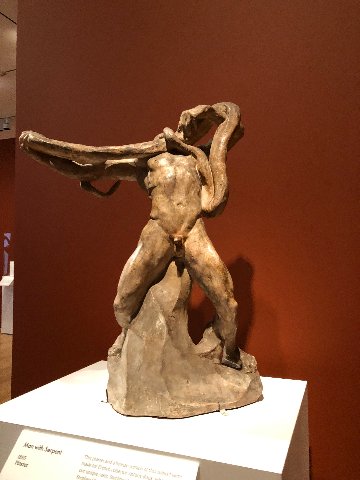

In Brussels, Rodin created his first full-scale work, The Age of Bronze, having returned from Italy. The figure drew inspiration from Michelangelo's Dying Slave, which Rodin had observed at the Louvre. The standing figure, is posed unconventionally with his right hand atop his head, and his left arm held out at his side, forearm parallel to the body.

In 1877, the work debuted in Brussels and then was shown with jury resistance at the Paris Salon. Its naturalism and lack of allegory defied the accepted norm. Rodin was accused of surmoulage or taking a cast from a living model. He vigorously denied the charges. One result is that he no longer crated life-size figures. His most popular works were created at varying scales from figurines to monumental. In the Clark exhibition we see versions of The Thinker at half size and monumental.

Part of the resistance to the work was his manner of innovation. There is a blown up image of the studio cluttered with casts. He would recycle elements to create new works.

Unless carefully wrapped in wet rags clay models can deteriorate. This was the fate of a torso at risk of being lost. Rodin attached it to an unrelated pair of legs and it was cast as Walking Man which resembles the similar composition of his John the Baptist. Once we know that Walking Man was collaged we note the very different treatment and surface of the rough torso and its smooth legs.

As his reputation grew in America he attracted leading collectors.

Katherine Seney Simpson (1868-1943) and her husband, John Woodruff Simpson, met Rodin through a dealer and visited his Paris studio. Katherine began posing for a marble portrait bust. It’s on view as well as a head study that he donated to her. They formed their own collection, and encouraged friends and museums to acquire his work. Although she was instrumental in helping to develop the Metropolitan’s Rodin collection, Simpson donated her own collection to the newly formed National Gallery of Art.

American actor, dancer, and choreographer Loïe Fuller (1862-1928) served as an agent for the artist, promoting his drawings and sculptures through exhibitions in New York (1903) and Cleveland (1917), as well as offering works to collectors. Fuller donated Rodin sculptures to the Cleveland Museum of Art and facilitated sales to West Coast collectors, including Alma de Bretteville Spreckels and Samuel Hill.

While Fuller is described as a "friend" of the artist, given his rapacious nature, we wonder if there was more to it. We know that he was shot down attempting to seduce another famous American, avant-garde dancer, Isadora Duncan.

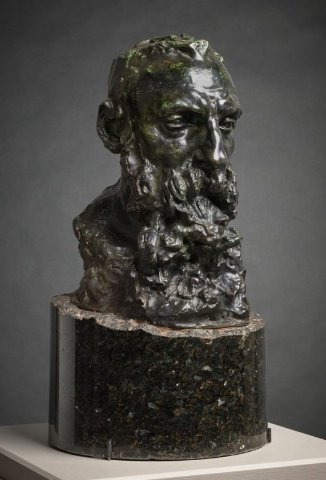

Alma de Bretteville Spreckels (1881-1968) married a much older man who made a fortune in sugar. He was the original “sugar daddy.” She loaned and later donated sculptures to the Legion of Honor Museum in San Francisco. (She and her husband also gave the museum building to the city.) Masterpieces Spreckels gifted to the Legion of Honor were bronzes such as The Prodigal Son (cast 1914) and Fallen Angel (cast probably 1915), as well as the remarkable portrait bust of Rodin by Camille Claudel, all featured in the exhibition.

Samuel Hill (1857-1931), a businessman and railroad executive, founded the Maryhill Museum in Goldendale, Washington in 1926, donating more than eighty Rodin sculptures and drawings to the museum. Le Normand-Romain visited the remote museum to secure loans for the exhibition.

We asked Le Normand-Romain if there were particular challenges in assembling a large exhibition of sculpture. "Not really," she replied "As I knew the work. But the pandemic created delays and difficulties." As to securing loans "I had to persuade the Baltimore Museum of Art to loan its large Thinker which I regarded as essential to the exhibition. It has never left Baltimore."

Jules E. Mastbaum (1872-1926) created the world’s largest theater chain. He visited the Musée Rodin in Paris and commissioned bronzes from the museum. The monumental bronzes Mastbaum acquired included The Gates of Hell and The Burghers of Calais. He displayed his collection at the Sesquicentennial Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1926 and began plans to create an independent museum on the city’s Benjamin Franklin Parkway. The Rodin Museum was a gift to the City of Philadelphia in 1929. Several works acquired by Jules and Etta Mastbaum are in the exhibition.

Gerald Cantor (1916-1996) became interested in Rodin after seeing a marble Hand of God (carved 1907) in New York in 1945. With his wife Iris (b. 1931), they formed a foundation through which they donated pieces by Rodin to institutions including the Brooklyn Museum of Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Center for the Visual Arts at Stanford University, Palo Alto, California. It holds an encyclopedic collection of Rodin bronzes, particularly objects cast after Rodin’s death. The Cantors supported the Musée Rodin’s efforts to produce posthumous bronzes, including the monumental Gates of Hell. The fifth bronze version of this portal was cast in 1981 for display at the National Gallery of Art’s Rodin Rediscovered exhibition, and is now part of the Cantor Arts Center’s collection. On display in this exhibition is the Cantor Arts Center’s The Age of Bronze (cast c. 1910–20) as well as the posthumous bronze of Dance Movement H (cast 1965).

This exhibition was not presented as a retrospective but rather as a quasi documentary. It would be remiss, however, not to take the occasion for critical evaluation. It is impossible to see such a profusion of work, familiar and arcane, without a plethora of thoughts, insights and conundrums. So much so that I spent a lot of time thinking, reading and evaluating the work.

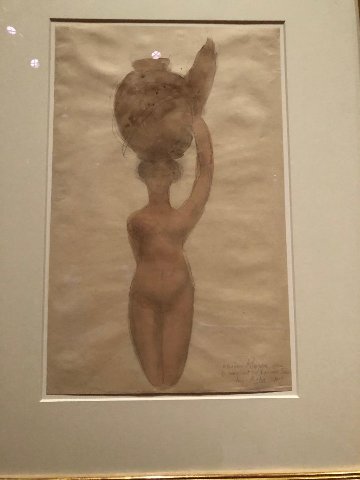

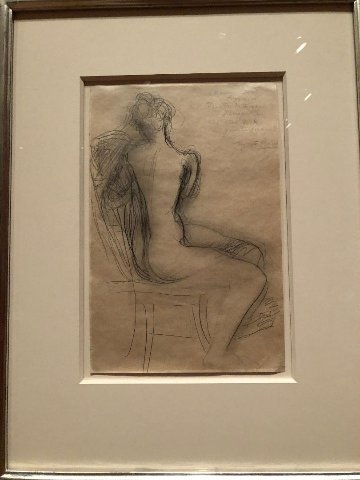

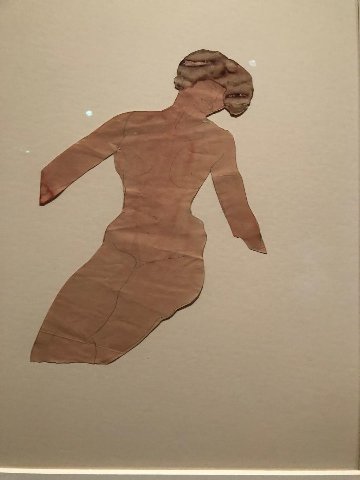

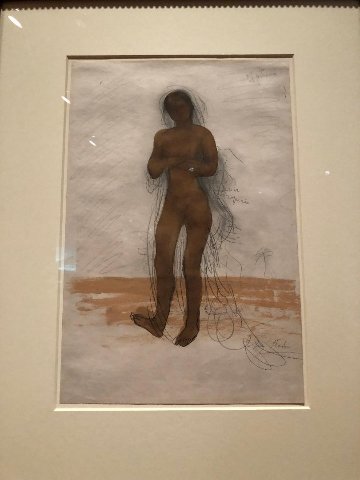

This past weekend we revisited with friends one of whom is an artist. It was a very different experience to view the work when galleries were crowded with visitors. But it allowed the chance to sense the responses of the general public. A way of measuring that is the amount of time and attention to any individual piece. Very little of which, for example, seemed directed to the drawings which indeed are subtle and surrender their essence reluctantly. This was the aspect of the work that I most appreciated during the second go round.

It was also the opportunity to reconsider what had shocked, surprised, and appalled me initially. It's the issue of taste and how it changes.

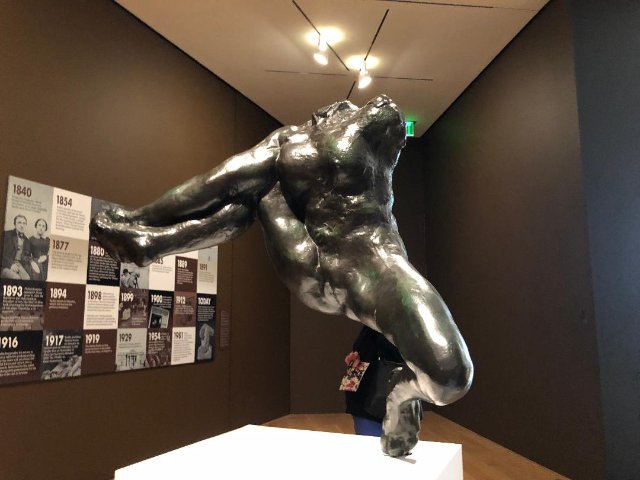

There was the jolting discovery of Iris, Messenger of the Gods (1895) which is unlike anything else in the oeuvre. The piece was new to me and outrageous in its truncated eroticism. The headless woman balances on one bent leg with the other out-thrust and held up by her arm. I puzzle over the meaning of her splayed vagina. What did the artist mean by such a bold pose? In what sense does this signify Iris?

It was intriguing to learn that it had been given to the Museum of Fine Arts Boston in 1898 by Edward Perry Warren. Deemed too erotic to display it languished in storage and was deaccessioned in 1953. No doubt the MFA would be glad to have it back but it was snapped up by the Hirshorn Museum. It is yet another sad Boston story of the one that got away.

At the end of her tour I asked the curator, Le Normand-Romain, which did she prefer, the marbles or the bronzes? Her reply was “It depends upon the piece.”

By that I hope she meant the intriguing Cupid and Psyche the intricate centerpiece of the exhibition.

To my taste I found the marble sculpture ranging from ludicrous to hideous. Figure of a Woman, The Sphinx (original model before 1888, carved 1909) is pure kitsch and seems like it has been carved from soap. While the bronzes convey the additive touch of the sculptor, in the work of technicians, the marbles do not.

Rodin traveled in Italy where he admired Donatello and worshiped Michelangelo. There is no mention of Bernini.

Previously, we mentioned that Rodin has been inspired by the Slaves by Michelangelo in the Louvre. They are the only finished pieces from his massive but abandoned project for the tomb of Julius II. He was taken off the job by Leo X and sent to Florence to create tombs for the Medici Chapel.

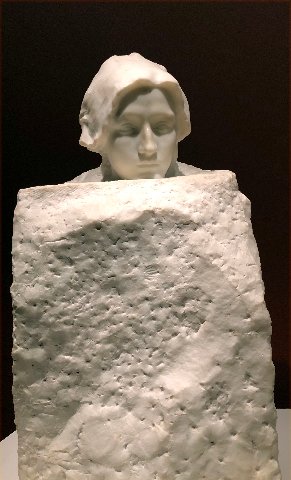

The unfinished, life-size figures of slaves flank a corridor that leads to the colossal David in the Accademia. Michelangelo had the Neo Platonic inspiration of finding and liberating the figure from its block of marble. Rodin wrongly conflated the look of unfinished, raw, rough chiseled stone as the aesthetic of the master.

We see that absurdly in two works displayed side-by-side Ceres and Thought. They are literally block heads. The highly polished smooth heads are plunked onto massive blocks of roughed out marble. Indeed what a waste of stone.

De gustibus non est disputandum.