Mary Ann Unger Reconsidered

Retrospective at Williams College Museum of Art

By: Charles Giuliano - Aug 13, 2022

In 1985, the Museum of Modern Art mounted An International Survey of Painting and Sculpture. Only 13 women out of a total of 169 artists were included, which led to the formation of Guerrilla Girls, an anonymous protest group.

A poster was later created by the troupe that listed hundreds of women in the visual arts, including artists, curators, critics, and art historians. As I perused the roll call, I recognized perhaps 20 percent of the names — including Mary Ann Unger (1945-1998). (At the time of her death, Unger was a member of the Guerrilla Girls.)

In the director’s foreword to Mary Ann Unger: To Shape a Moon from Bone (through December 22), the artist’s first retrospective in 20 years, Pamela Franks writes, “The project builds upon the Williams College Museum of Art’s decades old dedication to the work of female artists, curators, and scholars. With To Shape a Moon from Bone we join the timely investigation undertaken by so many art museums in our cultural moment, to expand the legacies of Minimalism and the archives of early conceptual art practice to include women.”

The project began four years ago when Williams curator Horace Ballard connected with the artist Eve Biddle, a Williams alumna and daughter of the artist and photographer Geoffrey Biddle. Ballard has since been appointed Theodore E. Stebbins Jr. Associate Curator of American Art for the Harvard Art Museums.

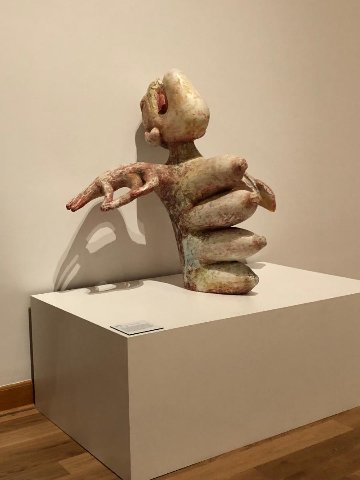

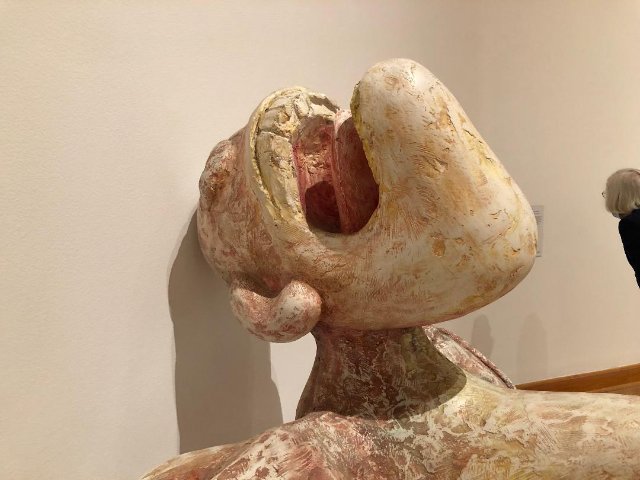

A key work in the exhibition is the gut-wrenching Supplicant (1985), an expressionistic sculpture created with hydrocal, a super strong version of plaster. A head is thrown back, its mouth open in extreme anguish. The torso is made up of a vertical row of four bullet-like breasts. It evokes Diana of Ephesus, the fertility goddess, though with myriad breasts.

After a 14-year battle with breast cancer Unger died at the age of 53. In her New York Times obituary, critic Roberta Smith wrote that “(Mary Ann Unger’s) works occupied a territory defined by Eva Hesse and Louise Bourgeois. But the pieces combined a sense of mythic power with a sensitivity to shape that was all their own, achieving a subtlety of expression that belied their monumental scale.”

Unger created several architectonic, neoconstructivist public art commissions. At Mount Holyoke she switched from science/technology to fine arts. After a hiatus of 10 years she earned an MFA in 1975 from Columbia Universit,y where she studied with Ronald Bladen and George Sugarman.

In the late ’80s, her works Temple and Beehive Temple were added to the Philip and Muriel Berman Museum of Art at Ursinus College and the Sculpture Gardens at Lehigh University, respectively. In 1989, she was commissioned by the City of Tampa to create The Wave. Her Ode to Tatlin was commissioned by the Aaron Copland School of Music at Queens College in 1991.

In 1989, she received a Pollock-Krasner Foundation grant, and would again in 1995; she was also a resident fellow at Yaddo in 1980 and 1994, and in 1992 earned a Guggenheim Fellowship.

The installation at the Williams College Museum of Art is dense, eclectic, and obfuscating. Numerous unlabeled drawings generate confusion. There is a selection of Eve Biddle’s work as well as contextualizing works by other artists in the museum’s collection. The curator wants visitors and students to do their own thinking about what they see — but there is quite a lot to unpack.

For many of her drawings, Unger used grids as a means to explore systemic abstraction and patterning. There are also some interlocked metal sculptures that reflect that approach.

A seismic change occurred after Unger’s self-referential 1985 breakthrough. Other totemic works made of hydrocal followed, with many of the goddess and spinal forms evoking the work of Bourgeois.

A key construction was one of her last, Shanks (1996-97), which has been acquired by WCMA. It is made up of three massive, bonelike objects, cradlelike structures made to lean against a wall.

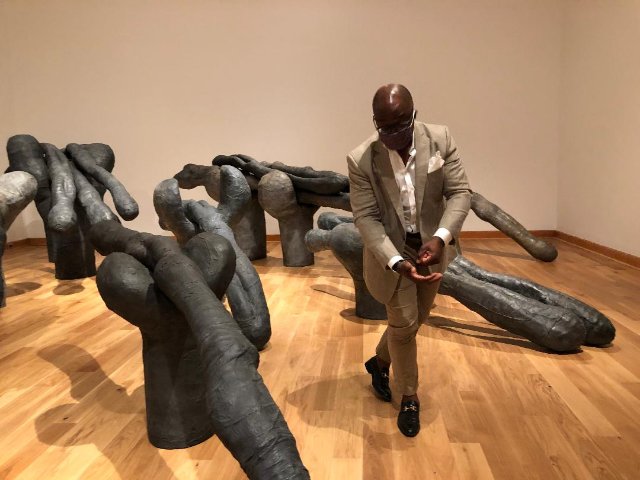

Unger also made a number of small bronze stick-figure expressionist pieces. Hydrocal could be patinated to resemble bronze, but large works were beyond her means. She worked alone in a 2,000-square-foot loft. The space included her husband’s darkroom and living amenities. Later they bought property in upstate New York. A major raison d’être for this reevaluation of Unger’s art is the gallery that contains her singular work Across the Bering Strait. Drawing on hydrocal, it comprises more than 30 pigmented post and lintel pieces. When Ballard first encountered this ambitious piece, his response was “Wow!” In that nanosecond he committed to the Unger show.

In her artist’s statement Unger wrote:

Across the Bering Strait is about the past, but it is also about the present. Populations are shifting all over the world today, refugees from battle or oppression, hopeful immigrants and adventurers pursuing dreams. They carry their nationalities and their cultures with them just as they carry their possessions. We may have our hopes for an information superhighway and our dreams of an interconnected world in the technological twenty-first century, yet it is still the movements of peoples that makes us aware of each other around the world: migration is arguably the strongest force towards the creation of a global village. Just as it made the world larger thirty thousand years ago, it is still people moving, migrating, and even literally walking, that is making the world smaller today.

Unger was inspired by her Jewish heritage as well as how ancient indigenous people crossed from Asia into the Americas. Initially, the work was exhibited with exotic lighting and a sound track of Tibetan and Inuit chanting.

Clustering and density increases in the work from front to back. The long segments of hydrocal-soaked cloth evoke metaphors of labor, burden, and carrying. Migrating people must take everything with them.

Unger’s motivation for this piece is heroic and admirable, but in the current climate of critical discourse Across the Bering Strait must negotiate a minefield of issues. The problem of appropriation is front and center. The act of an artist from a dominant culture claiming to tell the traumatic story of another, more challenged, culture is dismissed as a form of creative theft by the proponents of “cancel culture.”

Essays by Ballard and Zoe Dobuler in the show’s catalogue articulate this difficulty in detail. There are references to the complexities of “The Carrier Bag Theory of Evolution.” Ballard has opted to cut the problematic soundtrack and downplay the lighting.

That said, are visitors supposed to feel some sort of guilty pleasure if they find Across the Bering Strait powerfully mesmeric? Ironically, this paradigmatic work may be one reason to reposition Unger in art history. Is WCMA helping to accomplish that goal — with a damning asterisk?

Reposted courtesy of Boston’s Arts Fuse.