Trisha Brown at Jacob’s Pillow

Company Celebrates 40 Years

By: Charles Giuliano - Aug 14, 2011

Trisha Brown Dance Company

40th Anniversary Celebration

Ted Shawn Theatre

August 10-14, 2011

Artistic Director, Trisha Brown; Choreographic Assistant, Carolyn Lucas; Rehearsal Director, Diane Madden; Production Manager, Caleb Wertenbaker; Stage Manager, Sarissa Sulliman; Executive Director, Barbara Dufty.

Dancers: Elena Demyanenko, Dai Jian, Leah Morrison, Tamara Riewe, Nicholas Strafaccia, Laurel Jenkins Tentindo, and Samuel Wentz

Program

Les Yeux et l'âme (2011)

Choreography, Trisha Brown

Music, Pigmalion by Jean-Philippe Rameau, recorded by William Christie, and Les Arts Florissants for Harmonia Mundi

Set, Trisha Brown; Costumes, Elizabeth Cannon; Lighting, Jennifer Tipton

Dancers: Elena Demyanenko, Dai Jian, Leah Morrison, Tamara Riewe, Nicholas Strafaccia, Laurel Jenkins Tentindo, and Samuel Wentz

Foray Forêt (1990)

Choreography, Trisha Brown

Music, Traditional marching band music, courtesy of Jason Sulliman. Recording by Ben Handel’s Studio.

Costumes, Robert Rauschenberg; Lighting, Spencer Brown with Robert Rauschenberg.

Dancers: Neal Beasley, Elena Demyanenko, Dai Jian, Leah Morrison, Tamara Riewe, Nicholas Strafaccia, Laurel Jenkins Tentindo, and Samuel Wentz

Spanish Dance (1973)

Choreography, Trisha Brown

Music, “Early Morning Rain” written by Gordon Lightfoot and performed by Bob Dylan

Dancers: Elena Demyanenko, Diane Madden, Leah Morrison, Tamara Riewe, and Laurel Jenkins Tentindo

Set and Reset (1983)

Choreography, Trisha Brown

Original Music, Laurie Anderson

Set and Costumes, Robert Raushenberg

Lighting, Beverly Emmons and Robert Rauschenberg

Dancers: Elena Demyanenko, Dai Jian, Leah Morrison, Tamara Riewe, Nicholas Strafaccia, Laurel Jenkins Tentindo, and Samuel Wentz

When does the avant-garde become mainstream?

During a 40th anniversary of the Trisha Brown Dance Company at Jacob’s Pillow we were provided with a selection of works spanning from 1973 through the present. During the 1960s Brown was a part of the experimental Judson Dance Theatre which was a matrix for multi media work that drew together leading New York choreographers, dancers, visual artists, composers and musicians.

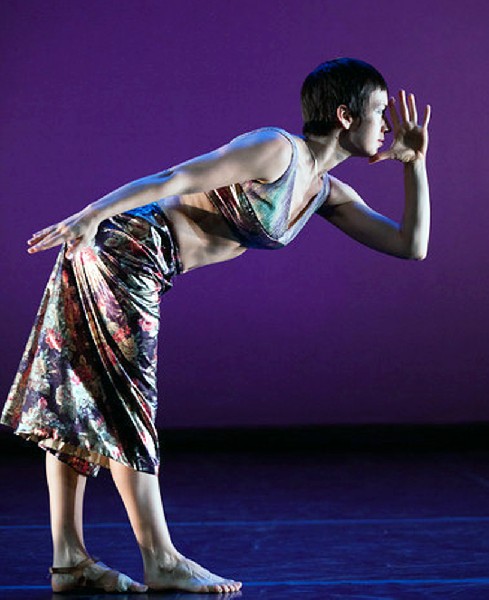

While the initial intention might have been to break out of the box what we experienced at the Pillow were works and a company situated well within the paradigm of contemporary American dance. In particular the first and most recent work Les Yeux et l'âme in which the gray tunics over pants designed by Elizabeth Cannon evoked a visual reference to the Classical Greek. Set to Pigmalion by the French baroque composer, Jean-Philippe Rameau, the movement was both edgy and reflective of the signature style of Brown, developed over the past four decades, as well as subtle, subdued and more classically modernist than barrier crashing.

While the mood of Les Yeux et l'âme evoked Fifth Century B.C.E. Greece one searched in vain for a literal telling of the famous story of the sculptor Pigmalion that created such an exquisite female figure that she came to life and became his lover. While the dancers interacted with the music, not always the case with Brown, she may evoke a classic legend but is not seemingly inclined to render a literal or at least easily discernable narrative. The story may be embedded in the dance but it would take a more practiced eye than mine to readily extract it from her vocabulary of movements that emphasizes upper body gestures, lifts and holds as well as silhouettes of hands and arms. There is a lot of colliding, falling to the ground, and hands pushing the head to the side as if it were a mechanical object.

In the second and last works on the program, Foray Forêt and Set and Reset, there was no seeming connection between the dance and the music. This was a signature of the New York School.

The approach was discussed during a video interview between choreographer, Merce Cunningham, composer, John Cage, and visual artist, Robert Rauschenberg. With great humor they described dances in which they all created simultaneously as well as individually. The commonality was that they started and stopped at the same time.

There was a similar sensibility in the dances we viewed.

In Foray Forêt, for example, the dance began with no music and sustained as such for quite some time. There were varying combinations of dancers until this diminished leaving a solo female. Ever so softly and gradually we heard the marching band music. It grew louder as she was joined by more combinations of dancers. The music reached a loud and insistent peak with the beat of a number of snare drums in a military tempo and then subsided again and disappeared.

We were intrigued by the variations of mottled mettalic costumes by Rauschenberg. The male dancers wore pants and were bare chested. The women also wore pants and skirts with variations of bandeau bras and bolero jackets. The dance ended when a woman appeared solo with a kind of loose gauze dress which distinctively set her apart from the other dancers. As she danced there were arms reaching out to grasp her from the wings. This was sustained for an interval and then abruptly ended.

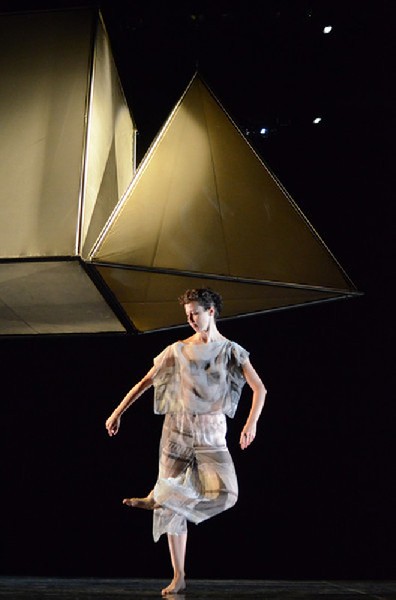

Rightly or wrongly the most compelling and interesting work of the program proved to be Set and Reset (1983). It was the most literal in conveying the multi media interactions of the New York avant-garde with sets and costumes by Rauschenberg and an electronic score for voice, percussion and synthesizers by Laurie Anderson.

The set comprised a large translucent cube in the center flanked by two pyramids. These were suspended above the floor. Onto them the artist projected a black and white collage of found film footage. The material was selected randomly and suggested no literal narrative or direct connection to the dance. He also created his signature silk screen designs on the ephemeral pants and tops of the dancers.

A trope of the New York School was best articulated by Cage. He liked to take deliberate and confining decision making out of the creation by employing what he described as “chance operations.” He would set a list of variables in advance. These were then selected in the process of throwing the changes of a hexagram conforming to the ancient Chinese book or oracles The I Ching.

Not to say that Brown literally followed the process of Cage and Cunningham but she appears to have channeled and been motivated by that zeitgeist.

The single work in the program that stepped away from that mode of chance operations was short, sweet, witty and endearing to the audience.

In Spanish Dance (1973), which opened the second half of the program, five women with white pants and shirts walked through the aisle and onto the stage. They formed a line with spacing of several feet between them in front of the drawn curtain.

As Bob Dylan performed “Early Morning Rain” by Gordon Lightfoot the woman on the end, stage left, began to move with her hands in the air and shuffling feet. She move to her right and eventually collided with the back of the woman next to her. After a pause, this second woman repeated the action and the two, touching, moved as a unit and collided with the third. The three then collided with the fourth and eventually the fifth. There was suspense as the song was reaching its conclusion. The now five women joined into a single moving entity, collided into the wall and abruptly stooped in time with the end of the song.

It was simple and accessible. The audience applauded the one piece in the program that seemingly everyone understood and appreciated. See, the avant-garde can be fun.

I have been grappling to understand and convey what I experienced. The seeming randomness of the movement and its endless collisions, groupings, couplings, crashes and recoveries.

What I have come up with is recalling a scene from the play Copenhagen in which Werner Heisenberg explains his theory of the Uncertainty Principle to his colleague in the field of quantum mechanics, Niels Bohr.

To quote from a definition “The uncertainty principle is certainly one of the most famous and important aspects of quantum mechanics. It has often been regarded as the most distinctive feature in which quantum mechanics differs from classical theories of the physical world. Roughly speaking, the uncertainty principle (for position and momentum) states that one cannot assign exact simultaneous values to the position and momentum of a physical system. Rather, these quantities can only be determined with some characteristic ‘uncertainties’ that cannot become arbitrarily small simultaneously. But what is the exact meaning of this principle, and indeed, is it really a principle of quantum mechanics? (In his original work, Heisenberg only speaks of uncertainty relations.) And, in particular, what does it mean to say that a quantity is determined only up to some uncertainty?”

Observing the seemingly random choreography of Brown is it possible for the viewer to find some predictable, determining factors? Can one intuit an algorithm that informs and motivates the sequences and intervals of the dance? Is there a structure? As we have discussed it is not possible to find that specific relationship in the music. Unlike most dance here it is an ambient rather than an informing element. Perhaps and most likely a template is there but so abstracted as to be remote from less than the most informed of her practice and intentionality.

As is so often the case in the most extreme contemporary arts, one is best advised to just enjoy the whole and not look for the sum of its parts. Perhaps as Susan Sontag suggested in 1963 it lies within the realm of work that is Against Interpretation.

Or, as Alfred Lord Tennyson wrote in 1854 “Theirs not to reason why,

Theirs but to do & die…”

Exactly.