Asher Lev at Barrington Stage Company

A Hasidic Jewish Artist Violates the Second Commandment

By: Charles Giuliano - Aug 24, 2011

Asher Lev

By Aaron Posner

Adapted from the novel by Chaim Potok

Directed by Adam Posner

Scenic Design, Daniel Conway; Costume Design, Olivera Gajic, Lighting Design, John Hoey.

Cast: Daniel Cantor (The Men), Renata Friedman (The Women), Adam Green (Asher Lev)

Barrington Stage Company

Pittsfield, Mass.

Through September 11, 2011

The novel Asher Lev by Chaim Potok describes the coming of age of a gifted boy in conflict with his Hasidic Jewish parents. It follows the discovery and development of his skill as an artist and pursuit of the forbidden Second Commandment.

Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth: Thou shalt not bow down thyself to them, nor serve them: for I the Lord thy God am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children unto the third and fourth generation of them that hate me; And shewing mercy unto thousands of them that love me, and keep my commandments. (Exodus 20:4-6)

The 1972 novel premiered as a play by Adam Posner in 2009. Since then it has had some 50 productions including Barrington Stage where, through strong ticket demand, it has been extended to September 11.

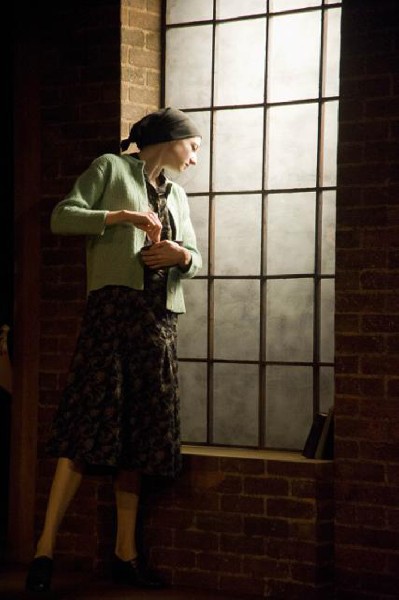

The three actors Adam Green (Asher Lev) Daniel Cantor (his father Aryeh Lev) and Renata Friedman (Rivkeh Lev) are tested to the limit of their range and skills. Green conveys Asher from childhood through maturing as a young artist. Cantor also performs as the Rebbe or elder and leader of the Ladover Hassidim in Brooklyn. And as the, feisty, flamboyant, non observant Jewish painter Jacob Kahn who tutors the boy. Friedman in a brief nude scene portrays the model whom Kahn hires to give Asher instruction in figurative drawing. She also appears as the Madison Avenue art dealer, Anna Schaefer, who successfully shows and sells Asher’s work.

The play compellingly conveys the deepening of the boy’s commitment and skill as well as the ever widening rift between the artist, his father, and eventually the Hasidic community.

His mother, played with compassion, anguish and nuance by Friedman is torn between protecting her son with his iconoclastic passion and her orthodox Jewish husband. He travels the world on missions for the Rebbe and has been told to relocate the family to Vienna. Asher wishes to remain in Brooklyn as he does not speak German or French. She has her own troubles resulting from the accidental death of her brother Yaakov. In a poignant scene she begs her husband for permission to pursue Russian studies and continue his life work.

In the Barrington production the action occurs in the simple, poor apartment of the Lev family. There is a central table around which they gather for kosher meals or to discuss complex family issues. The pragmatic scenic design by Daniel Conway features a window out of which she stares in melancholy as well as a back wall of opaque panels. These are illuminated according to an elegant and appropriate lighting design by John Hoey.

While the play is set in a Hasidic family in 1950s Brooklyn it could be about any artist coming of age in opposition to the wishes of his or her family. Often parents fear for the poetic ambitions of their children as violating tradition or representing an unfamiliar world and a life full of uncertainties.

One thinks of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man by James Joyce or Sons and Lovers by D.H. Lawrence.

For an understanding of the Lev family it is important to comprehend how Hasidism differs from other forms of Judaism. In general it is closer to Orthodox than to Reform Judaism.

The Hasidic movement started in the 1700's in Eastern Europe in response to a void felt by average observant Jews of the day. The founder of Hasidism, Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov was a great scholar and mystic, devoted to both the revealed, outer aspect, and hidden, inner aspect of Torah. In contrast to the intellectual style of the mainstream Jewish leaders of his day, and their emphasis on the primacy of Torah study, there was a constant focus on attachment to God and Torah no matter what one is involved with. Today, Hasidim are differentiated from other Orthodox Jews by their devotion to a dynastic leader (referred to as a "Rebbe"), their wearing of distinctive clothing and a greater than average study of the inner aspects of Torah.

There are perhaps a dozen major Hasidic movements today, the largest of which (with perhaps 100,000 followers) is the Lubavitch group headquartered in Brooklyn, NY. For Asher Lev, the author Chaim Potok created the Ladover Hassidism named for a fictional town in Russia. It resembles the Lubavitch Hasiddim one of the most open and worldly of the Hasidic groups.

There is also the issue of the lack of traditional Jewish art. Because of the taboo of the graven image it is only in the 19th and 20th century that we encounter the oxymoron Jewish artist. One of the first was the impressionist Camille Pissarro and then the modernists Marc Chagall, Chaim Soutine and Amedeo Modigliani. There were many Jewish artists among the American social realists and abstract expressionists. During the depression years the leaders of Boston Expressionism included Jack Levine, Hyman Bloom and Karl Zerbe.

There are elements of Judaica and symbols derived from the Kaballah in modernist and contemporary art but, like Asher, many Jewish artists drew inspiration from Christian iconography. Not only did the boy outrage his father by depicting nudes but by copying scenes of the crucified Christ. His father accuses him of glorifying Jesus in whose name Jews have been persecuted.

In this Asher was not alone. Consider the famous White Crucifixion by Chagall. Christ is depicted as a Rabbi and surrounded with iconography derived from the Yiddish tales of Sholem Aleichem.

The compelling play begins and ends with an incantation.

“My name is Asher Lev. The Asher Lev. The ‘notorious’ and ‘legendary’ Lev, the painter of the Brooklyn Crucifixions. I am an observant Jew. A Hasid. What some call a ‘Torah Jew.” And, yes, of course, observant Jews do not paint crucifixions. In fact, observant Jews do not paint at all in the way I am painting. So strong words have been written and spoken about me and myths are being generated. I am ‘a traitor,' ‘a self hater,’ ‘a blasphemer’ and ‘an inflictor of shame upon my family, my friends, and my people.’ And, of course, myself. Well, I am none of those things. And, of course, in some ways I am all of those things. But I will not apologize. It is absurd to apologize for a mystery.' ”

Kahn has instructed him to paint what he feels. That channels into a body of work comprisiing portraits of his family and ancestors. The key works depict images of his crucified parents. They plan to attend the opening but are concerned about nudes as was the case in the first exhibition. Over the dinner table he assures them that there are no nudes this time. But he lacks the courage to inform them about the provcative family images.

We see Asher during the well populated and successful vernissage. He is being hailed as a prodigy and many works were sold to eager collectors before the opening. Asher is surrounded by well wishers in the crowded gallery when his parents enter. The crowd parts like the Red Sea. Slowly they examine the painting in shocked silene then leave.

After the “triumph” of his second exhibition the artist briefly remains at home. There are grim silent meals. In the synagogue he is shunned by the congregation and is told by the Rebbe to leave and go back to Paris. There is a difficult departure where his father does not speak but shakes his hand in a gesture of good luck.

We can only speculate that having paid such a terrible price for his career there is enough tsouris, drive, ambition and inspiration to sustain him through a life in the arts. For any artist, no matter how gifted, that’s a big and uncertain question.

By then, there wasn’t a dry eye in the house.