Edwin Dickinson's Provincetown Years

Major Exhibition at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum

By: Charles Giuliano - Aug 30, 2007

Edwin Dickinson: The Provincetown Years, 1912-1937

Curated by Mary Ellen Abell

July 20 through September 23

The Provincetown Art Association and Museum

460 Commercial Street

Provincetown, Mass. 02657

Catalogue: Acknowledgements by Christine McCarthy, Essays by Mary Ellen Abell and Helen Dickinson. 176 Pages, illustrated, with selected bibliography, List of Public Collections, Selected List of Exhibitions, and Chronology. Printer, Kirkwood Printing, Wilmington, Mass. Published by Provincetown Art Association and Museum, 2007

508 487 1750 fax 508 874 4372

http://www.paam.org

The major exhibition "Edwin Dickinson: The Provincetown Years, 1912-1937" with 97 works including several of his best known, large scale paintings, as well as smaller paintings, a selection of drawings, and a series of etchings which have only recently come to light, involving loans from numerous museums and private collections, would simply not have been possible until now. The PAAM which was founded in 1914 in America's oldest and most famous artist's colony (which dates to the 1890s) has recently completed an expansion and renovation of some 4,500 square feet which approximately doubles its prior space.

The PAAM is a multi tasking organization which combines an art association with numerous shows of its members, past and present, an ongoing teaching institution, and also has an extensive permanent collection of more than 2,000 objects. It includes works by over 600 artists, dating from the 1900s, with connections to the Lower Cape. In order to implement this expansion of the physical plant and ambitious programming such as the current Dickinson exhibition, the museum's director, Christine McCarthy, initiated a $5 million capital campaign from 2004-2006. For a seasonal community, with a relatively short list of potential donors for the several arts organizations, this represents a remarkable accomplishment. As one indicator of the success of this effort membership has increased by 25% in the past 18 months.

Visiting for the first time in several years we were impressed by the changes. The older part of the complex retains much of its original character and personality; but completely renovated, upgraded and most importantly, climate controlled. In the past it was not uncommon to sit through a sweltering event during the summer. But that wonderful original space, comprising two large galleries, and a smaller space which was the former entrance and shop area, retains much of its character and personality. It was fun to recognize the large benches on which many years ago I sat with then director, Ellen O'Donnell, and interviewed the local historians, Nat Halper, and Tony Vevers, while undertaking research.

My interest at the time was Karl Knaths who arrived in Provincetown just prior to World War One about when Dickinson first came to study with Charles W. Hawthorne. Later Provincetown would be famous for the summer school of Hans Hofmann which attracted many young artists some of whom were veterans on the GI Bill just after World War Two. There was the period of the Sun Gallery, in the 1960s, which showed the figurative expressionists: Bob Thompson, Lester Johnson, Claes Oldenburg, Tony Vevers, Jan Muller, Jay Milder, Red Grooms, George Segal and others. Allan Kaprow staged one of his early Happenings at Sun Gallery. There was a lively scene of seasonal galleries and good jazz at Reggie Cabral's A House.

Early on Provincetown was cheap and the Portuguese fishing community was tolerant of artists and their bohemian ways. It was one of the few places in America where one could be openly gay. It was as good a place as any to endure the hard times of trying to make it as an artist. Ironically, today, other that an aging community of long established individuals, artists have been priced out of the Lower Cape by a staggering inflation of real estate. Today there is the Fine Arts Work Center which runs a wonderful winter residence program for artists and writers but Provincetown is no longer a place for young artists to hang out. Back in the 1960s, when I was a college student, it was still possible to sleep in the dunes and pick up a loaf of fresh bread at dawn in the Portuguese Bakery on Commercial Street. But, as Daniel Ranalli recently reported for us, shacking up in the Dunes is the last remnant of that lifestyle.

During research on Knaths it became apparent that the three most important modern artists of the early years were Knaths, Dickinson and Ross Moffett. Anyone researching one of these artists is likely to encounter the others. Before the arrival of Hofmann they were the dominant forces and exponents of modernism. In recent years, an interest in feminism and the Provincetown White Line Prints, has unearthed such artists as Blanche Lazzell, Maude Squires, Ethel Mars and Agnes Weinrich. Knaths was married to Helen Weinrich and Agnes, his sister in law and colleague, died rather young. Tongues wagged when Knaths built the house in which he lived with the sisters. It is ironic that today there appears to be more interest in Weinrich, and her rather small surviving oeuvre, than in Knaths. Part of this comes from the abominable handling of his estate and a lack of children and heirs to sustain his legacy. His work was liquidated by the bank serving as trustees. Pages from notebooks and journals were torn out and stamped to be sold at whatever price possible. This is not the best way to sustain an artist's reputation. So there were formidable obstacles to research on Knaths.

But there was always a sustained interest in Dickinson. This exhibition and its catalogue refreshed my memory and the fascinating issues of early American modernism, and the generation of the Armory Show. The range of works on view begs the question of just where Dickinson belongs in the pantheon of American Art. In a review in the Boston Globe, the critic, Ken Johnson, states that "The artist never pulled together the two sides of his creative nature- the slow and the fast, the complex and the simple, the visionary and the perceptual. The split persisted throughout his post-Provincetown career, during which he divided his time between homes in Wellfleet and New York. Had he found a way to integrate the two sides, would we remember him today as one of the greats of 20th-century American Art? Perhaps. But maybe it's just as well that he remains a semi-secret treasure. That way, each new generation of art lovers can wonder upon rediscovering him, 'How come we never heard of this guy?'"

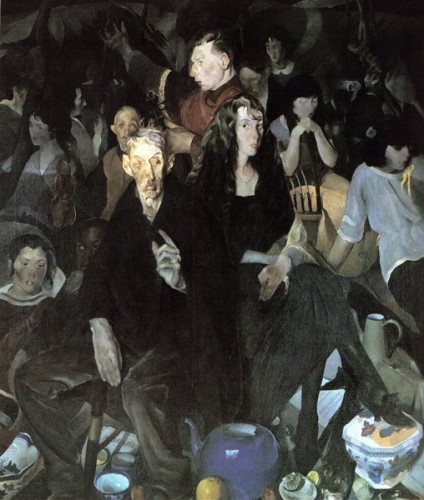

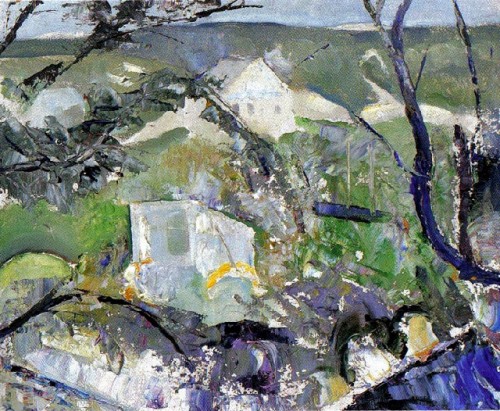

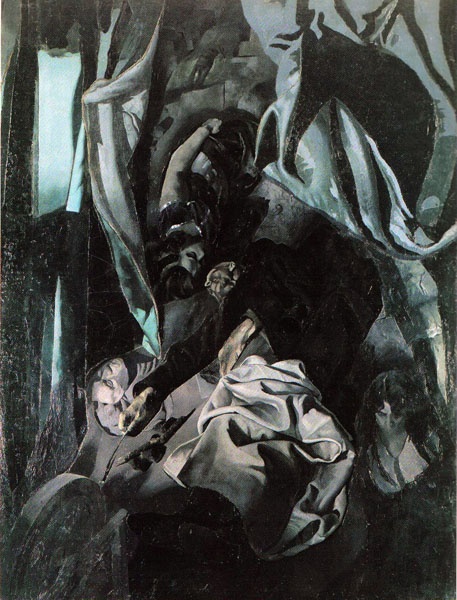

Yes, that seems fair. There are indeed many conundrums to encountering Dickinson and finding the right place to consign his accomplishments. It is more daunting when an artist opts to be multi valent producing very different kinds of work simultaneously as was the case for Dickinson. He made the remarkably abstract "first strike" or "premier coup" pictures, meant to be completed in a single burst of energy, as well as the large, complex, dark, somewhat labored and academic pieces that deliberately defy precise interpretation. The quick pieces often inspired by atmospheric views of nature put him on the cutting edge of international abstraction during the era of World War One. He was inspired in this direction by his mentor Hawthorne and they seem closer to J.M.W. Turner than the Synthetic Cubism that Knaths learned through Weinrich who had studied abroad with Albert Gleizes. In the large, dark, ambitious works which took in the hundreds of sessions, compared to the one shot sketches, Dickinson appears to be influenced more by the mannerism of El Greco than the avant-garde. Hawthorne is viewed today as an academic artist who produced landscapes, still life paintings and portraits of fishermen and young boys. Hawthorne was a great teacher and proved to be a magnet drawing students and artists to Provincetown. In his informal works, including a series of works on paper shown some years back in the Hudson Walker Gallery of the Fine Arts Works Center, we saw his fresh and experimental approach. Dickinson appears to have picked up on both aspects of Hawthorne's work.

The challenge of confronting Dickinson (as well as Knaths and Moffett) was that in some aspects they were remarkably inspired, progressive and inventive, as avant-garde as Georgia O'Keeffe and Marsden Hartley, and in other ways they were traditional and conservative particularly as later generations of Provincetown painters (particularly Hofmann and his students) passed them by on the fast track of modernism. The best approach is to view them as simultaneously experimental and conservative. But after Hartley's German Military series during World War One, and O'Keeffe's works of the same period, might not the same be said of these artists who are now comfortably ensconced in the first tier of American art of the 20th century? Isn't that ambivalence really a characteristic of American modernism? So why come down so hard on Knaths and Dickinson who were fighting the good fight of the avant-garde in a sleepy little fishing village at the tip of Cape Cod? Had they lived in Manhattan would their position be different today? And consider that both Hartley and O'Keeffe were represented by Alfred Stieglitz the only American art dealer of his generation who mattered. The early monotypes by Knaths from 1913-1914, some signed Otto Knaths, are as abstract and experimental as any global work of its time. One might compare his early abstractions to the simultaneous efforts of Vasily Kandinsky and Frantisec Kupka. Or the American Arthur Dove.

While this exhibition is a great accomplishment for the PAAM, particularly in securing loans of so many representative works, the scholarship of the curator Mary Ellen Abell, and essays by Helen Dickinson, the artist's daughter, leave too many important issues and questions unchallenged. There is too much attention given to what has previously been reported and little effort to advance our understanding of the work of the artist, his peer relationships, singular accomplishments, or provide an adequate critical analysis of his style and subject matter. Too often when attempting to deal with large, complex, narrative works, Abell quotes from the writing of other scholars. We don't sense that she has significantly added to critical thinking about the work. And there are many lapses. The catalogue does not provide the dates of the exhibition. It is stated that when Dickson spent his first winter in 1913 there were two other artists living there at the time. These individuals are never identified. One of these artists may have been Knaths. The chronology is helpful but ends abruptly in 1937 when the family left for Europe. We are informed that they wintered in Buffalo in 1938-39 and bought a home in Wellfleet in 1939. And wintered in New York after 1944. The last entry, after 1937, informs us that Dickinson died in 1978. A more complete chronology, beyond the time frame of the exhibition "The Provincetown Years," would have provided a more useful scholarly publication. The rather thorough list of exhibitions ends in 2002 with "Edwin Dickinson: Dreams and Realities" at the Albright Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York. What would it have taken to bring us up to date on the exhibition activities of the past five years? In the bibliography there are articles cited by Jean Bergantini Brillo as well as Jean Bergantini Grillo. Both in (The Cambridge) Phoenix, which was later acquired by Boston After Dark and is know today as the Boston Phoenix. The critic's correct name is Grillo.

The greatest disappointment of this exhibition is that when there is a major project such as this, and there are scholarly and technical lapses, they tend to go uncorrected. When a curator or critic fails to make a compelling argument on behalf of the artist, or makes mistakes, they undermine the long term evaluation of the artist. As Ken Johnson implies it may a generation before we wonder why we never heard of this guy.

In a conversation with a colleague who has seen the Dickinson show, and whose opinion I greatly respect, he was too ready to consign Dickinson to the second tier of artists of his generation. I responded "No, you are wrong. Dickinson was an artist of the first rank." There are works in this exhibition that are absolutely brilliant, galvanic and stunning. They match up with the best work of his generation. But, with time, and perhaps worn down by melancholy which is hinted at in these essays, and surviving America's daunting indifference to artists and their work, Dickinson may have cut back on his drive and ambition. There are a number of safe and less challenging works in this exhibition, landscapes which might have been done by any number of artists, or, arguably, his Provincetown followers. Unfortunately, one such work graces the cover of the catalogue and coveys the wrong message. The painting is an all too familiar and romantic view of P'Town in subdued washes of color.

The catalogue once again tells us the charming tales of artists getting mackerels from the fishermen on the dock. Or carousing with their mates. There are the family anecdotes and references to his extensive diaries and journals. The artist, apparently, declined to explain the symbolism of his work. So his writing is mined for clues but provides few answers. What we really want to know, for example, is what he learned from Hawthorne. What did he and the other early modernist artists talk about during quite winter months in the drafty, cold studios of Day's Lumber Yard? Just how did Dickinson relate to that remarkable community of artists? How was he similar to but different from his peers? Where would you properly place him in the community of artists? For the answers to those and other scholarly questions we may have to wait for another generation. Arguably, Dickinson will remain one of those great American artists you never heard of.