More on Wagnerism by Alex Ross

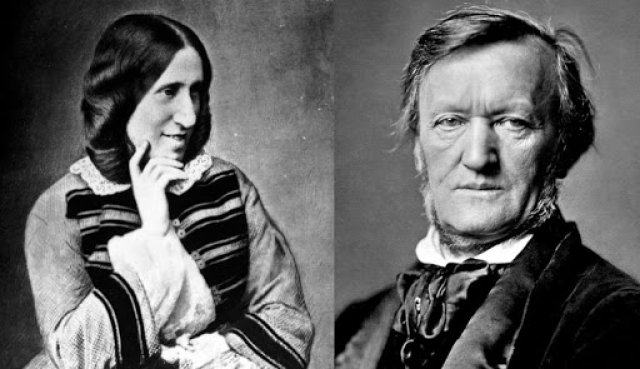

George Eliot Absorbs Wagner

By: Susan Hall - Sep 10, 2020

Wagnerism

By Alex Ross

Published by Farrar, Strauss and Giroux

Wagner’s impact on literature was enormous, and Alex Ross, without a stretch, portrays his influence in vivacious detail.

When Wagner’s music crossed the English Channel, it attracted the attention of novelist and critic, George Eliot, who always took a great interest in music. Early on, she identified Wagner’s achievement as a path to the future, writing “…anyone who finds deficiencies in opera as it has existed hitherto...” must admit that Wagner “…has pointed out the directions in which lyric drama must develop itself, if it is to be developed at all.”

As portrayed by Ross, Eliot did not swallow the Meister whole. She had difficulty with the length of the composer’s works and later with the man himself, although she and her partner, George Henry Lewes, found Wagner’s wife Cosima splendid.

In Wagnerism, Ross brings us into new dimensions of Eliot’s heart and mind. The novelist and her partner left for three months in Weimar, Germany, not long after their first exposure to Wagner. There they visited with Franz Liszt, the composer’s father-in-law. Performances of Wagner’s music were everywhere in town and the Lewes’ enjoyed them.

In her final work, Daniel Deronda, Ross shows how Eliot broke the frame of the domestic novel. Here is a work of huge scope in which leitmotifs bind the structure. Like The Flying Dutchman, endless isolation and the search for home dominate the novel. There is a common pattern of absence and return. Eliot weaves these themes through many characters in the novel, indicating that they are not themes limited to one person, but rather universally human.

Parallel stories in the book are joined by one common theme; opera. Curiously Eliot draws a distinct moral line between characters who love music, most of whom are Jewish, and those who do not.

While Eliot was disturbed by Wagner’s anti-Semitic writing, she did not discuss it in her essays. Deronda, about a man discovering his Jewish origins, may have been her subtle commentary on the subject. She was clearly not an anti-Semite.

After the death of George Henry Lewes, Eliot married their close friend, John Cross. He was twenty years her junior and very handsome. On their honeymoon, Cross leapt from their hotel window into a Venetian canal, escaping Eliot’s yearning and unattainable erotic desires which had been fanned to new heights by the Meister’s extravagant music. Cross survived.

What a dramatic conclusion to Eliot’s torch for Wagner: erotic desire beyond any hope of satisfaction.

For all the British enthusiasm for the Meister’s music, until Glyndebourne was founded, no production on the British Isles came close to the composer’s wishes. While Glyndebourne is associated with Mozart, in fact, John Christie, who transformed his back gardens into an opera production space, loved Wagner first and foremost. It was Bayreuth that inspired his creation.

His son recalls that he was such a Germanophile that he dressed for dinner in lederhosen, wearing braces and a black tie. "He was always hankering to bring Parsifal to Glyndebourne for an Easter Festival" and was only derailed from that enterprise by his wife.

George Bernard Shaw knew the Wagner operas as did Oscar Wilde. The most distinguished inheritor of the flame on the British Isles may be James Joyce. His construction of Ulysses has many Wagnerian elements. Ross wrote his senior thesis at college on Ulysses. A Wagnerite emerged.

Ross in Wagnerism not only satisfies, but leads you back to the music. This giant composer's contribution may be one of the few artifacts of a future world. Response to him was widespread and overwhelming. Reading Ross's engaging and enlightening book makes remembrance of Wagner's work a tormenting and tantalizing pleasure.

Part III of IV on Wagnerism.