Yankee Stadium A Fan's Farewell

A Final Visit to The House That Ruth Built

By: Steve Nelson - Sep 12, 2008

BABE RUTH IS DEAD. That's the banner headline on the New York Post. It's August 17, 1948. I'm seven, old enough to read it. My family is on vacation in Connecticut, but we're from the Bronx, a couple of miles up the Grand Concourse from Yankee Stadium.

I'd already been to a game there. My father got us tickets in the right field stands, down front. We were a little late, arriving with the game just underway in the top of the first inning. As we walked down the aisle to take our seats, there was a loud bang as bat hit ball, followed by the roar of the crowd. We stopped and looked toward the field, as New York Yankees center fielder Joe DiMaggio came gliding back toward the wall, in his effortless-looking way, and made a nice running catch. The hometown fans cheered, and thrilled at the sight of Joe D and the Stadium, I was hooked as a true-blue Yankee fan.

Not that my loyalty wasn't tested. One of my young friends in the Bronx was a New York Giants fan, another a Brooklyn Dodgers fan. And in an effort to show me the error of my Yankee ways, each of their fathers took me and his son to a game, the Giants at the Polo Grounds, and the Dodgers at Ebbets Field, a night game no less. I wasn't swayed, but at least I got to see all three classic New York ballparks.

In 1950 my parents followed the post-war exodus to the suburbs of Long Island, where I played Little League. A lefty and a good hitter for average, I was too small to have much power, although I did once hit a walk-off grand slam to win a game. Well, truth be told, it was a single to right which skipped past the outfielder and kept going while I circled the bases and slid home head first with the winning run. One Saturday morning all the local teams assembled at a high school athletic field, where a movie was being shot about Little League with Yankee pitching star Whitey Ford. As a relatively small guy for a major leaguer, and a lefty, he was one of my heroes. No, I never got to take a swing against Whitey, but at least I can say that I was on the same field with him.

In the 1960s I moved to Massachusetts. Living in the home turf of the arch rival Red Sox, I maintained my steadfast loyalty to the team from the Bronx, but from afar, with an occasional TV game (there was no cable, of course) and in the sports pages. Then about ten years ago, through a friend in the cable business, I got a couple of free tickets to a game at the Stadium. My Dad had passed away years before, so I took my younger brother Rich, who still lived on the Island. It became a ritual for the two of us to attend a game together every year, mostly thanks to tickets I scored on eBay.

This spring, we knew it would be our last game at the old Stadium, which was to be torn down after the season and replaced by the most expensive stadium ever built in the U.S., with a price tag of $1.3 billion. Rich was going to be on vacation in August, so I watched eBay for tickets during the week he was off. Prices were starting to skyrocket, as fans snatched up seats for the few remaining games. I managed to find some in my favorite place, in the upper deck behind home plate, with a panoramic view of the field and the Bronx beyond it. With a face value of $25 for the season ticket holder who sold them to me, they went for $75. Similar seats might fetch $1000 or more for the very last home contest in late September against the Orioles of Baltimore, Ruth's home town.

It's August 17, 2008, exactly 60 years since that headline about the Babe. I'm on the road early Sunday morning for the three-hour ride from the Berkshires to meet my brother for the game. As usual, I take the less-traveled route to the Stadium by driving through the Bronx, rather than approaching by highway. This means heading south down the Grand Concourse, a wide boulevard which in its better days in the '40s was lined with deco apartment buildings home to an upwardly mobile working class. I find a free parking spot on the street several blocks north of the Stadium and walk toward the Bronx County Courthouse through Joyce Kilmer Park. Yes, that Joyce Kilmer. It is said that a tree grows in Brooklyn, but the man who thought it more lovely than a poem is memorialized in the borough hated by Dodger fans.

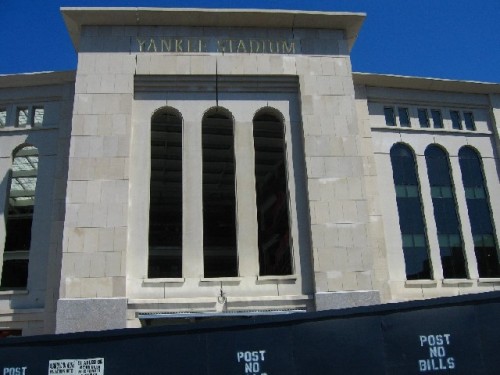

From the park across the street from the Courthouse I first spot the Stadium, its left field stands looming above the Bronx. I take a right down 161st Street, walk past the delis and bars and souvenir shops catering to fans, then under the elevated subway tracks to join the crowd milling outside before the game, getting a bite to eat and taking souvenir photos. The new Stadium is rising across the street, but I only give it a glance and take a snapshot. Because I'm here again, for the last time, at "The House That Ruth Built." The Babe was the star of the team when the field opened in 1923, constructed at a cost of $2.5 million. He was a hard living outsized celebrity who commanded the unheard-of salary of $80,000 a year. Today, Alex Rodriguez makes twice that for a single game.

In 1927 Ruth hit 60 home runs, a record which stood until 1961, when Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris spent the season chasing each other in a quest to break it. At the time I was living in an Indian village called Vicos high in the Peruvian Andes, a college student in an anthropology program which was the inspiration for the Peace Corps. Teddy Kennedy visited us there on behalf of his newly-elected brother. But my big excitement was getting the Sunday New York Times sports section in the mail, which my parents sent me every week so that I could follow the exploits of the M&M boys. When I returned to the States in the fall, Mick went down with an injury after reaching number 54, still the home run record for switch-hitters. Maris got number 61 in the Stadium in the last game of the year.

It's those countless legendary players and plays and moments and games which give the Stadium an unmatched mystique and place in baseball history. But watching the backs of the souvenir t-shirts worn by the fans, it's obvious that four numbers are the ones that really count. 7, worn by Mantle. 5, worn by DiMaggio. 4, by Lou Gehrig. And of course the Babe's 3. Of the current crop of players, Derek Jeter's 2 is the big one with the crowd, easily topping A-Rod's 13.

When my brother arrives on the el, we hike up to the upper deck. It's a beautiful day, and the field glows in the summer sun. Rich and I have a winning streak on the line, because the Yanks have never lost a game we attended together. Things get off to a bad start when the lowly Kansas City Royals score three runs in the top of the first. But in classic Yankee style, they come roaring back with four home runs to win 15-6. Jason Giambi hits a grand slam to right, not far from where my Dad and I sat, and A-Rod sends a solo shot over the left-center fence which lands among the monuments honoring late Yankee greats. Our streak intact, my brother and I high-five. And as Frank Sinatra's "New York, New York" plays over the P.A., we leave the old Yankee Stadium for the final time.

Next year I'll be back on eBay looking for two tickets to a game at the new Stadium. But one thing I won't be able to buy is a ticket back in time to the place where so many legendary players left their mark. Not long after Joe DiMaggio died in 1999, Rich and I attended a day in his honor. Everyone in the park was watching the ceremonies at home plate when Bob Sheppard, the Yankees' public address announcer since 1951, asked us to "please direct your attention toward center field." Standing there, seemingly having appeared from nowhere, was a small figure with an acoustic guitar. When he began to sing, everyone immediately recognized that it was Paul Simon. His words carried over the P.A. system across the field: "Where have you gone, Joe DiMaggio?"