Boston Artist Thad Beal: Beer and Burgers

From Law to Fine Arts

By: Charles Giuliano - Sep 21, 2013

Thad Beal: Beer and Burger

Reposted from Maverick Arts Magazine, February 11, 2006

Honestly, I had every good intention of visiting the first New York, one man show, by Thad Beal, at Robert Steele Gallery, 511 West 25th Street, from November 13 through January 7. At the last minute our trip and reservations at the National Arts Club were cancelled because of a blizzard. As luck would have it that weekend I came down with a brutal and mysterious fever which lasted through an absolutely miserable exam week culminating in a visit to the emergency room and an overnight stay in the hospital. Pretty scary.

But my profuse apology didn’t get me very far as with great restraint and understatement he reminded that he had on two occasions endured blizzards to honor me; first at a sparsely attended one man show at Thayer Academy, and secondly to join me when hosting a stellar dinner for fellow critics and artists at the National Arts Club. So, I owed him, not once but twice over. While Thad does not forget, he does forgive. It is just one of his many remarkable qualities and social assets. He has a great ability to make other people feel good about themselves. While the one on one beer and burger conversation was stunningly brilliant, he always makes you feel just as smart. Given his distinguished Brahmin heritage the words to describe his demeanor might be manners, breeding and noblesse oblige. But he carries this off with a lightness of touch, warmth, and generosity of spirit that finds him at home and comfortable in any setting, from rural India, to wolfing down a sandwich at his desk during a stint working in the West Wing.

The focus of our dialogue was sharing the results, emotions and insights of having his first one man show in a major, street level, large, Chelsea gallery. At the age of 57, by New York standards, he is an emerging artist. Great opportunity but not terrific timing as the opening, attended mostly by his friends, coincided with Miami Basel when most of the New York art world was out of town. There were no reviews and perhaps this is the only media attention although Thad has gotten lots of great press for his extensive exhibition history in the Boston area. I have always regarded him on the shortest list of Best Boston Artists.

“I have a piece of paper in my wallet that states that I am a lawyer,” Thad said with robust humor and irony. “But there is nothing that I can produce in that manner which quickly confirms that I am an artist. However pathetic it may seem, having a solo New York show makes me feel much more self assured as an artist. It was a large show with 14 works in a great space. The paintings ranged from small to up to 6 x 8’. Significantly, when it became known that I was having a New York show an important curator called and came to the studio just before I had to ship the work.”

While he didn’t want to elaborate on the point, or cause any embarrassment to the curator, it is an all too familiar anecdote. Peers and colleagues in your own community are the last to value what is under their own noses. It is only after out of town recognition that you get some respect back home.

Given the importance of the event I asked if he had been nervous. “It’s a lot like what I learned when arguing a case before a jury,” he said evoking an analogy from his years as a trial lawyer. “If you are not adequately prepared, you’re cooked. There is nothing you can do at that point. I feel the same way at an opening. I want people to respond to the work but if they don’t there is nothing that I can do about it.”

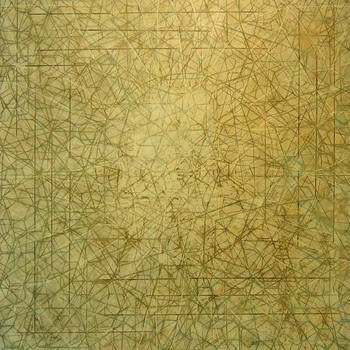

When I visited the gallery website (www.robertsteelegallery.com) the installation and images I viewed were consistent with works I had seen over the past few years. There is a layering to the work that involves beige or cream colored background into which is a dense incising of thin lines forming constellation and maze like patterning on overlapping levels. There is obviously some overlying mathematical equation driving this design but I am not equipped to grasp that meaning. But I allow myself to enjoy and absorb art, to respond emotionally to pleasures for the eye, even if they elude the brain. It is how, for example, I might tour museum galleries of Islamic and non Western art about which I have only basic knowledge. The statement on the gallery website references this Islamic approach and states that the work reflects “The West’s Fear of Infinity.”

While I have learned by now not to ask artists to “explain” their work, particularly if it is “non objective,” as is the case here, I strongly feel it is acceptable to initiate a dialogue about the set of ideas and inspirations that inform a body of work. It is a way of talking about things that can’t be talked about. As one very bright and tough artist has insisted to me repeatedly “If I could explain my work I would be a writer and not a painter.” But we have spent many hours and days debating the meaning of that sentiment. And in an odd way I think I understand differently but perhaps even better than the artist himself because he has made me work so damn hard. Truth is, if you want to be a good critic, it means that you are always playing someone else’s game by their rules. It is both challenging and fun; particularly when you win, which is at least some of the time. Astrid often asks me why I approach everything as combat.

“I am trying to capture the energy of life in a non narrative way,” Thad said. “My work is more like music than story telling and it is not polemical. I go out of my way to give real world references. But if a line comes into work that suggests perhaps the shape of a tea pot or some other recognizable object I will eliminate it. I will dispossess it of narrative content.”

That reminded me of an important Kandinski “Improvisation” an “abstract” painting owned by the Art Institute of Chicago which is commonly known as “Cannons.” It has forms in a corner that “read” as those objects. The painting was executed just prior to WW1 so the interpretation, rightly or wrongly, that the artist had a subliminal embedded response to the notion of imminent war which just was séanced into the work. Or so we have come to regard the painting in hindsight. It is a common tendency to want to find hidden meaning in the seemingly random. People see images of Jesus and Mary embedded in a frosted window or a sandwich which goes for mega bucks on E Bay. God in your oatmeal. There was a controversy during the Vietnam War era when the former nun, Corita Kent, was commissioned to paint a huge tank for the Boston Gas Company. Bostonians quickly identified the profile of Ho Chi Minh embedded in a blue stripe. It is interesting that Kent is dead, and the painting has since been restored, but the former Vietnamese revolutionary, true or false, remains, although people today don’t much care.

“The work is more like a gerund than a noun,” Beal continued. “It is a state of being. I am fascinated by mathematical dialectics and philosophical conundrums. But my work is not an illustration of those interests. I am involved with devices that animate and express states of the mind and processes. There is a scientist who has analyzed the patterns in Pollock drip painting and he concludes that Pollock was different from other random pattern makers because he was inherently fractal. That come out of Chaos Theory and is derived from fractional dimensions. It means a lot of things at once.”

This past week in the New York Times there was an article about just such an analysis of known samples of the work of Pollock and a group of recently unearthed paintings that are alleged to be by the artist. By applying the technical analysis of the patterns in known Pollocks, in comparison to the patterns in the new works, a scientist has stated that they are probably not authentic based on his research. This leads to the suggestion that the seemingly random and improvisational gestures of Pollock were likely much more precise and controlled. Which has always been evident by empirical observation. Science is only confirming what has long been obvious to the trained eye. But it is a bit mind boggling to contemplate such technical analysis of a Pollock. That his spontaneous work conforms to theoretical mathematics. Here Beal seems to reverse the process from fractals back to “spontaneous” art. So Pollock is a bookmark for his work.

Like Kandinsky and Matisse, Beal arrived at art after abandoning law. While they were disgruntled law students Beal was a senior partner in the old Yankee firm of Nixon Peabody in Boston when he began to question his life and career in 1985. Perhaps until then his life had made too much predictable sense. From Yale, class of 1969, yes he remembers George W. Bush staggering around the campus, he went onto law school, Stanford class of 1973, because at the time “Everyone wanted to go to law school. It was the logical and obvious thing to do. I wanted to get to the west coast and as far away as possible from my roots in New England.” He spent five years at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts (1985-1989) where he states that “I needed every minute of it to decompress.”

There was a lot of bad karma to overcome. It started during his senior year at Yale when he became quite ill. There was an initial misdiagnosis and he recalls being “pumped full of antibiotics which didn’t work.” He was languishing without much hope in the infirmary next to a celebrity athlete, Calvin Hill, a football player, and later father of Grant Hill, a basketball player. “They called in a lot of specialists for Calvin and during a consultation one of the doctors looked at my chart and stated that ‘This guy has Reiter Syndrome.’ It took another four or five painful months to recover and the symptoms slowly went away. I went home to Washington D.C. where my father was then the Undersecretary of the Army. I ended up working for Jean Meyer who was later the President of Tufts University. I worked for the Conference on Food and Nutrition and I had a desk in the Nixon White House for three months. It was pre Watergate. Looking back it was the perfect job because it ended after the Conference was held.”

When the Washington job ended he took off with a plan to circumnavigate the globe. Some nine and a half months later “I panicked in India. I had left with a letter of credit for $5,000, the world was a lot cheaper then, and I intended to travel for a couple of years. I got back just two weeks before starting law school.”

Just where did the art come from I wondered? He recalled visiting the World Fair and the only pavilion with no line was showing American Art. There he encountered with work of two great uncles; Reynolds Beal, and Gifford Beal. “I never met either one of them,” he said. “They were from my father’s side of the family with whom we had little contact. Gifford was the President of the Art Student’s League.”

But art was not a significant part of his own family background. He was more likely to be exposed to politicians and jurists. At the dinner table one was expected to be informed and brilliant. He recalls it as being terrifying. “McGeorge Bundy (one of David Halberstram’s ‘Best and Brightest,’ National Security Adviser to Kennedy and later Johnson) was my mother’s cousin.” Thad knew him well and added that his mother was from the venerable Lowell family. He recalls hearing Bundy describe himself as “A rapidly descending member of the ruling class.”

Given all that complexity and tradition it is remarkable that like those distant relative, Reynolds and Gifford, he is the third Beal to pursue a life in the arts. Of course, the ultimate irony is that his son now is considering a graduate degree in the arts. Working on my second pint I boldly asked if he is happy today. The answer is an unqualified yes but there is a bit of back story. It started when the woman he married, a poet, made the condition of moving from California back to Boston. Although now divorced they continue to have much in common beyond two wonderful children in their 20s.

So what does “happy” mean to a middle aged painter who came to his true calling after a long and winding road? Well, it means going to the studio every day and working long and hard. Doing terrific paintings that are only beginning to be appreciated. Spending weekends with a woman who also has an intensive life in the arts. Perhaps the meeting was devolving into beery sentiment. This is the point when I tend to burst into tears pricked by the slightest clues of memory. Perhaps to pull me out of a free fall into bathos Thad suddenly interjected saying “I only use one eye. Probably I see the world very differently than you do.” Perhaps that explains a certain flatness and schematic planar quality of the work. But I surprised him by saying, “Don’t be so sure of that. My right eye is shot and I will have cataract surgery on it this summer. I had the left eye, which is fine, fixed a few years ago.” But that seemed like a good exit line. Next time we will talk about something else. Like Pollock and Fractals. Unless there’s a blizzard.