Jackson Pollock Inspired Tennessee Williams

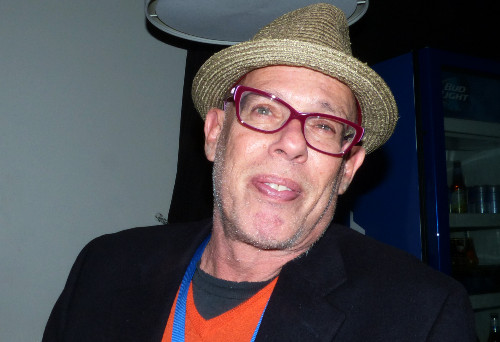

David Kaplan Discusses The Day On Which a Man Dies

By: Charles Giuliano - Sep 26, 2015

As a part of our coverage of the 10th annual Provincetown Tennessee Williams Festival we reviewed a play directed by David Kaplan who is the artistic director of the festival.

Knowing more about the art of Jackson Pollock than the writing of Tennessee Williams I questioned some of the assumptions of the playwright about the artist. The role in the play feeds the populist assumptions about mad artists. The Clark Art Institute, for example, attracted a record attendance for its exhibition of the landscapes of Vincent van Gogh. Many attended, we speculate, because of curiosity about an artist who cut off his ear, was confined to asylums and later shot himself. No doubt visitors studied the works intent on clues to his mental state. Ultimately, while emotionally charged, they were, well, landscapes.

The challenge of art is to look at the work and not think about the ear.

The Williams play, as directed by Kaplan, for my money, focuses on “the ear.”

I wrote. “During the afternoon we saw The Day On Which a Man Dies. It presents an ersatz Jackson Pollock, nude but for a thong, covered in paint, and using a sprayer as a tool and weapon. The artist has gone over the top in abandoning the brush in a bid to jump start a faltering career. If Williams is evoking Pollock his art history is off base. By abandoning the brush the artist created the most dynamic work of his generation. As his friend and rival William de Kooning said at the funeral (an accident/suicide) “Pollock broke the ice.”

“…While his behavior is out of control and a study in creative madness, arguably a caricature as films of Pollock at work show that he was in complete control…

Not long after the review was posted Kaplan responded ""arguably a caricature as films of Pollock at work show that he was in complete control" The beautiful rhythmic dance we see in the films of Pollock painting are true, but a partial truth. Direct from Tony Smith (father of Kiki) who had seen it with his own eyes, Williams knew that Pollock was drunk, stumbling, unwashed - in short a mess - at various points in his process -- and especially towards the end of Pollock's life. Ruth Kligman's book and, especially, "To a Violent Grave: An Oral Biography of Jackson Pollock" make it very clear Williams is presenting no caricature in Day on Which a Man Dies, but a variation on a reality (Williams' reality and Pollock's)..Pretty they weren't: Pollock, in particular could be monstrous in public and in private life, too. Of, course, it's not a portrait of Pollock that DAY ON WHICH is after -- but the seed of the monstrous in Flora Goforth and the painter can be sourced to Williams seeing himself in Pollock's self-destruction, alcohol abuse, and in particular, the suicidal car joy ride. Williams, as drunk as Pollock, tried to kill him self in Italy that way."

I replied by e mail that the major works of Pollock- Lavender Mist, Number One, and Autumn Rhythm,-were executed when he was sober. Studio photos of the artist at work show him in complete control dancing about the canvas spread out on the floor. Also I questioned some of his sources including the Pollock mistress, Ruth Klingman, who survived the crash that killed Pollock and her female friend, as well as remarks attributed to the sculptor Tony Smith.

Even when he resumed drinking, which led to a separation with Lee Krasner, the artist although in a troubled, terminal phase of alcoholism, continued to work in a stylistic shift and return to the figure which has come to be greatly valued by art historians, curators, collectors and museums. While on the brink of suicide his career was not "washed up" as represented by the over the top character in the Williams play.

Late last night following a performance during the Festival Kaplan and I interacted with a friendly, cordial and scholarly discussion. There was no time to delve deeply into details but he cited sources for his understanding of the play and the intention of Williams.

As he put it he never debates critical opinions of his work but does challenge factual errors.

This morning he followed up chapter and verse with what appears below. Some of this material is truly intriguing.

Hopefully at some point we will be able to sit over a beer and further discuss this and other topics related to the work of Williams and its unique relationship to Provincetown.

[1940] Toward the end of August, a girl entered the scene. I did not

regard her as a threat. And then one day I was on the dunes with a

group that included the yet-unknown, or uncelebrated abstract painter,

Jackson Pollock. Later on he was to become a "dark" man, outside his

work, but that summer I remember him for his boisterous, just slightly

drunk behavior. He was a sturdy, well-built young man, then, just a

little bit heavier from beer-drinking than was attractive to me, and

he used to carry me out into the water on his shoulders and to sport

about innocently.

[late in the Memoirs] The work of a fine painter, committed only to

vision, abstract and allusive as he pleases, is better able to create

for you his moments of intensely perceptive being. Jackson Pollock

could paint ecstasy as it could not be written. Van Gogh could capture

for you moments of beauty, indescribable as descent into madness.

AND, most telling:

Tennessee’s letter to columnist Max Lerner during [and about] the

creation of SWEET BIRD OF YOUTH (1959, around the same time as DAY ON WHICH:

“ As an artist grows older he is almost always inclined to work in broader strokes. The delicate

brush-work of his early canvasses no longer satisfies his demands of

himself. He starts using the heavy brush, the scalpel and finally even

his fingers, his thumbs, and even, finally, a spray gun of primary

colours. Act Two is written with that heavy brush, scalpel and

spray-gun. Delicacy, allusiveness are thrown to the winds in writing,

staging and performance.”

--