Palimpsests of Stephen Hannock

Oxbow Paintings Featured at Bowdoin College Museum of Art

By: Charles Giuliano - Sep 29, 2007

http://www.bowdoin.edu/art-museum

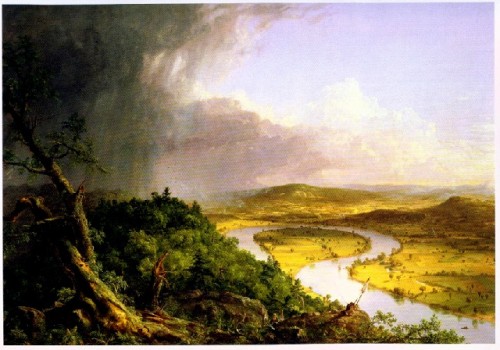

In 1836, the British born Thomas Cole (1801-1848) created a painting "View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm—The Oxbow" which is an icon of American art and a paradigm of the movement called Luminism by art historian Barbara Novak. Initially, it was argued that the group of artists including Cole, Martin Johnson Heade, Frederic Edwin Church, Albert Biersdtadt, and Asher B. Durand among others, comprised an uniquely American movement and phenomenon. That notion of originality and cohesiveness has been eroded by later scholarship which has broken down Novak's simplistic grouping. The artists vary far more in their individual approaches and subjects particularly the other direction of Cole in producing pot boiler narrative series such as "The Course of Empire" and "Voyage of Life." In the catalogue for the landmark "American Light" exhibition in 1980 it was suggested that the movement be renamed "The Glare Aesthetic" and was an approach that found direct parallels in the landscape painters of Russia and Denmark as well as in Northern European painting in general as it evolved from the Romanticism of Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840).

Because he has frequently painted views of the Oxbow, and a large painting by Stephen Hannock (born 1951, Albany, New York) "Oxbow, After Church, After Cole, Green Light," 1999, (eight by twelve feet) also hangs in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art just a few galleries away from Cole's view of the Oxbow, in the shorthand of knee jerk art criticism, it has become the norm to think of Hannock as a born again Luminist. Getting to know him first hand during a recent studio visit where he was putting the finishing touches on "The Oxbow for Leonard Baskin and David Becker (Mass MoCA#49)" a six foot by eight foot canvas with polished oil over acrylic and collage, which is about to be shipped to the Bowdoin College Museum of Art for its gala reopening on October 14, nothing could be further from the truth. Luminism? That was then and Hannock is now.

As the artist himself suggested there is some critical discussion about how his approach is presenting new possibilities for American landscape. When Cole traveled to Europe to paint the European Sublime he was reminded in a letter from Durand to not lose sight of "That Wilder Image." While America lacked classic Greek and Roman ruins, the stuff of Romanticism and inspiration for John Keats', 1884, "Ode on a Grecian Urn" that America's Sublime, based on the definitions of Edmund Burke (1729-1797), include such spectacular phenomena as Niagara Falls, the Grand Canyon, the Rocky Mountains and, here in Western Massachusetts, The Oxbow.

Hannock insists, with all due respect to the American landscape artists of the 19th century, that he comes by his views of the Oxbow, and other epic vistas, quite honestly. That he lived for a time in Northampton and painting the Oxbow became inevitable and a logo of his aesthetic identity. But his unique approach is to treat it as a palimpsest, a complex layering of collaged photo images, with references to people and places he associates with a site, as well as layers of text. They are a stream of consciousness commentary of lines evoked by nature just as Keats was inspired by that Greek pot.

The term palimpsest, which is a big word he tossed out during a lively, fun, and rather long session in the studio, refers to how parchment, which was rare and valuable before the invention of paper making, was recycled by writing and drawing over erased sheets in which ghosts of images were embedded under layers of new text and images. That occurred as a side aspect of recycling where here it is a deliberate aesthetic approach.

This encourages us to view the work both from a distance, absorbing the entire composition, as well as coming up close and intimate with the surface discovering its buried treasures and fragments of discourse. It reminded me of clusters of viewers elbowing each other to study the "Garden of Earthly Delights" by Hieronymus Bosch, ca.1450-1516, at the Prado Museum.

While we were talking about the subject of art criticism he mentioned a review that day of the Richard Prince exhibition at the Guggenheim by Roberta Smith in the New York Times. That inspired him to grab a marker and add a line about that to the painting. Exactly what that has to do with the Oxbow is beyond me. It was just a spontaneous gesture to memorialize a momentary thought. But I commented to him that this is precisely what will drive some future graduate student absolutely mad. It will surely fall to the task of a scholar to record and analyze every buried image or fragment of text. To come up with a cohesive theory of what it all means. Just as scholars pore over and publish the symbolism of Bosch. But in the case of Hannock there is both sincere intentionality as well as a bit of tongue in chic.

I asked if he ever saw people "reading" his paintings. The response was absolutely. It is precisely why his Oxbow painting in the Met has remained on view for the past six years and continues to hook and absorb viewers. Surely he is not the first or last to embed image and text in the work. One thinks of the collage and text of Picasso and Cubism, for example, but he represents a fresh and contemporary approach to a modernist conflation. What seems to work for him is a savvy combination of traditional approaches and techniques as well as hip twists and turns.

But he didn't learn how to do this in a grad program like Yale, Cal Arts, or Columbia. It is not what one is taught in school and like so many interesting and compelling artists, particularly those pursuing aspects of representational painting, he is largely a drop out and autodidact. With a big chunk of Leonard Baskin. Who taught him more about how to be an artist than to evolve as a Baskin clone. Unless you are told it would be difficult to intuit a direct connection between what Hannock is producing and the mentoring of Baskin a now very dated looking, illustrative, print maker, book designer and sculptor. When I was in school in the 60s, my professors, recycled Social Realists, were in awe of Baskin, Ben Shahn, Jack Levine, Rico Lebrun, Philip Evergood, Jacob Lawrence and other artists who are now seen and discussed only by scholars. Baskin fell off the map.

But he was still an art star and attraction in the fine arts program of Smith College when Hannock stumbled in for a semester in the 1970s. At the time he was a gym rat with pro aspirations as a goalie for Bowdoin College. He didn't do well in studio classes and dropped Baskin's class although he later worked for and lived with the artist. While he acknowledges that Baskin taught him how to draw there was a parting of ways when Hannock tried something new and got a lousy crit from the master. He realized that Baskin just missed the point of what he was attempting and it was the moment where he decided to break off and follow his own instinct. This is precisely when one becomes an artist in that ancient Oedipal struggle for originality and identity. Like Jackson Pollock as a student of Thomas Hart Benton.

He was also influenced by the sisters Bette and Agnes Mongan. Pulling out a photo collage he showed me a panorama with the sisters seated in the middle. The space to the right reveals the courtyard of the Fogg Art Museum where Agnes was curator of prints and drawing and to the left, the National Gallery, where Bette was curator of prints and drawings. He got to know Bette at Smith where she was a curator and she in turn introduced him to Agnes whom he visited frequently. When he showed her some drawings she compared them to Ingres and put out some examples for him to study. "I could have sneezed on them" he recalled. But when he later showed her a collage there was a cool reception. She called in several conservators who explained precisely how his work would fall apart because of the poor selection of materials. "See dear," she said making a point about trying to create works that will last.

But when he worked on the 1998 film "What Dreams May Come" directed by Vincent Ward and starring Robin Williams, Cuba Gooding Jr. and Annabella Sciorra, he was shocked to find that nobody took any interest in whether the many sketches, studies and paintings used in the film had any archival quality. The pros he worked with had no interest in such matters providing images with materials meant to last only through the shooting of the film. He pissed them off by insisting on using legitimate artist materials which only increased costs. They were also hostile to the fact that he leaped over them in rank and had unlimited access to the sets and production meetings. He approached it as an opportunity to learn first hand about filmmaking. He created a twelve foot triptych for the film which is a centerpiece in which Williams dies and goes to heaven through the painting. "For every camera position I show a beginning, middle and end." He was hired for the project, rather than a professional set painter and designer, because the director liked that he could produce a unique and unified view. For his efforts he earned an Oscar for Visual Effects.

He was impressed by the cinematic artists he worked with. "They could draw a complicated group of figures, anatomically perfect, like a cluster of bodies in Gericault's Raft of the Medusa, from memory. But they had no interest in creating their own original art." He managed to hold onto some of the studies but does not own the copyright and cannot sell them. He discussed giving some away to people who would appreciate them. While there was back biting and even sabotage on the set he earned respect when he solved an enormous rodent problem picking them off by tossing a deadly accurate Frisbee. Huh?

Yeah, that's right. "I threw Frisbees for a living," he recalled humorously. That occurred during his time at Smith when he didn't qualify for the Field Hockey Team and missed playing goalie for Bowdoin. It seems that nearby Hampshire College, which didn't have an athletic program, started a team that played competitive Ultimate Frisbee. "We went on to the National Finals," he recalled. "It was like football or lacrosse but a rule is that you can't advance when you possess the Frisbee. You have to toss it to another player. The object is to get it to a player at the moment when he lunges into the goal. A couple of us got real good at Freestyle Frisbee." Which is what endeared him to his peers on that rat infested movie set.

But this indicates Hannock's originality, experimentation and eccentricity. One of his earliest series of very large scale landscapes involved using phosphorescent paint which glows under black light. This work was shown at the Smith College Museum of Art and he was the youngest artist ever to be given a one man show by that institution. Teaming with a musician he showed them at Boston's Hatch Shell as well as Don Law's rock venues.

Somewhere along the way Hannock became a successful artist with impressive friends and clients in Hollywood and a best friend, Sting, who is godfather to his seven year old daughter. After 20 years in New York, where he still maintains a studio mostly as a pied a terre, four years ago, he moved to the Berkshires. He was largely attracted by Mass MoCA which is planning a large show of his work. Initially he arrived as a visiting artist at Williams during the same year that he was a visiting artist at Harvard. He found Williams far more dynamic and truly committed to art. Tom Krens, then the director of the Williams College Museum of Art, before moving on to the Guggenheim, gave him a show. Tom told him of plans to turn the campus of the former Sprague Electric company into an art museum in North Adams. Hannock became close to the late art historian, Lane Faison, who was an enormous influence of what has come to be known as the Williams Mafia of museum directors and curators.

Mass MoCA is so important to him that Hannock has started to catalogue his works by numbering them Mass MoCA 1, 2, 3, 4, etc. The area seems ideal as he got out of the hectic New York art world and is able to maintain a low profile while doing his work. When his wife passed on a couple of years ago he assumed the difficult task of being a single parent and answering his daughter's tough questions. Part of that experience is embedded in the work and in the Oxbow he pointed out some images, a snap shot of the daguerreotypes that he and his wife posed for by Chuck Close, and texts that are now largely invisible. There is a darkness of mood to the painting and subject of which he has created a number of versions. The precise time of day is twilight and the sun has just slipped down behind the horizon. Commenting on that I quoted from Longfellow "Between the dark and the daylight, when the night is beginning to lower, comes a pause in the day's occupation, that is known as theÂ…" I paused for him to fill in the line. Then continued "The children's hour."

The studio is busy and he is assisted by the artist David Lachman. When I arrived I was surprised that there is only one chair. The point is that they don't sit down. The studio is more like a gym or sports arena as they are in perpetual motion. Hanging in with them I found myself wearing down from being so long on my feet and keeping up with the artist's enormous physical presence and energy. There was always one more anecdote or insight which leads to another and another. Pity that poor grad student who eventually writes a dissertation on the work. What a subject.

At one end of the studio they were getting ready to push the Oxbow out the door while at the opposite end work was almost complete on a large work commemorating the 25th Anniversary of the Sundance Institute in Utah. The commissioned piece is a view of the valley that Robert Redford purchased with money earned from the successful film "Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid." Hannock discussed the many functions of the Institute which combines a for profit resort which pays for the activities of the institute of which the nearby film festival is a spin-off. Typically, the painting contains imagery and memorabilia as well as relevant text embedded in the surface.

In addition to the two works nearing completion another promised work for the Grand Rapids Museum of Art had just been shipped from the studio. He was able to show me a study of a view of Western Michigan. Grand Rapids was his wife's home town. Pressure came from the fact that the two promised paintings, for two museum expansions, came virtually simultaneously in addition to the Sundance commission.

Now at mid career and enjoying success and the company of famous friends I wondered if an artist gets boxed in by the pressure to produce? He expressed that it is not so surprising that he would have well known running buddies. It is the result of a natural process that by mid career the only artists left standing are those who have managed to establish solid careers. The rest have either dropped out or teach. "You get beat up by what life throws at you," he explained adding that there are always new projects and interesting subjects to paint.

Now that the studio is about to be cleared out he is excited about starting a panoramic aerial view of Newcastle, England, the home town of Sting, which he has commissioned. He showed me a study for the work from one of numerous views taken from a helicopter. "After awhile you can only do so many benefit concerts before people get a bit bored with you," he said. "Sting came up with another idea. The city is really changing and becoming a lively cultural center. It also has a rich history for its mining and industry." The photo study has so much detail that I suggested it would be a real challenge to render but Hannock stated that there would be a lot of editing and changes including adding allegorical figures. "If it comes out all right and they want it Sting plans to donate the painting to Tate Modern in London." Perhaps sometime down the line I will get a chance to drop by and see the work in progress. After all, Hannock is a local artist. Ain't that a hoot?