Benno Friedman on Painterly Photography

Berkshire Artist Overcomes Adversity

By: Charles Giuliano - Oct 01, 2014

When we were fine arts undergraduates at Brandeis University there were no courses in photography. For Benno Friedman that came later. He developed intuitively including mentoring through the late experimental photographer, Don Snyder. Early on they showed together.

Through frequent visits to his home, particuarly during holidays with an extended family of friends, I followed the remarkably consistent developmen of his fine arts work. On many levels, for me, he was a quintessential creator, role model and inspiration.

It was my great pleasure to work with him as curator of an exhibition for the gallery of the New England School of Art and Design at Suffolk University. It was his first Boston show in some time. Previously, he had been represented by the infuential Parker 470 and later Portia Harcus Gallery. In New York he was shown by the legendary former Light Gallery. It was, at the time, the foremost gallery of new photography. His work was shown in the prestigious Whitney Annual.

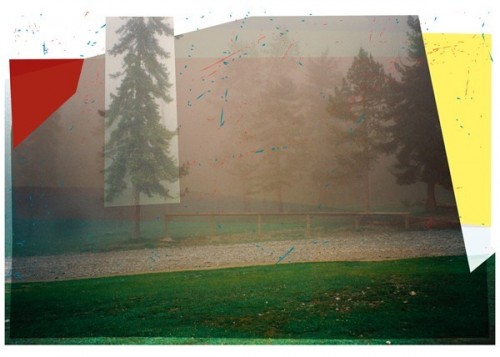

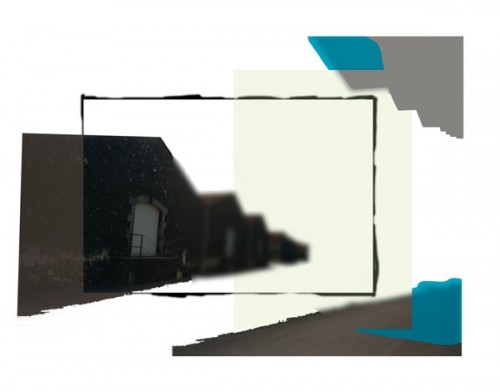

His painterly, experimental techniques of creating prints, however, fell through the cracks of the often conservative photography world. Traditionalist adhered to fixed notions of straight photography. He brought a sensibility of training in painting and sculpture to the notion of altered, painterly prints.

In that approach, arguably, he related back to the pioneering practitioners of Pictorialism who experimented with darkroom process and hand perpared papers striving to move photography closer to a fine arts aesthetic.

For Friedman, other than in his commerical work, taking a photograph was just the first step toward creating a satisfying image. That mandate has prevailed through the work from its inception to the latest digital practice.

Charles Giuliano You operated from a studio in New York but also built a darkroom in your Berkshire home. From visits during holidays it seems that you only emerged for dinner. Particularly when Don Snyder was in residence it seemed that your practice largely entailed the alchemy of the darkroom. There was a lot of experimentation with dyes and chemicals. Taking the image was the initial step of the ultimate process. As a fine arts photographer you were never a documentarian or straight photographer. Is that a fair assessment?

Benno Friedman That is. I wasn’t interested in the equivalent of going on Safari with a camera. For me there were two kinds of photography: Taking a photograph or making a photograph. I was clearly in the camp of making the photograph.

Originally I had been trained as a painter. I was learning about making sculpture and had a strong association with the abstract expressionists. The artists that came after them like Rauschenberg and Johns the various painters in that era whose interests extended into photography.

I wasn’t interested in the mechanical quality of photography. I was interested in the way it could capture something. That something for me was equivalent to stretching a canvas. What you captured in the camera, for lack of a better term, was the first step in making a photograph.

A number of philosophical questions came out of that for me. Originally, photographs were made with devices with lenses that put images onto papers with silver salts. After you made a print there were always dust specks. Foreign matter took away from the image you were interested in presenting. You retouched those spots with a variety of paints. I considered what would happen if you made a print and you spot toned out everything but the scratches.

That was my mindset. Metaphorically it went far beyond that particular idea. It was an open playing field. The subject matter in part dictated what it was asking me to do. So yes, I was entrenched in what people might call formalistic conceits about the actual materials and how they responded to light and other chemicals. I was much less interested in the specificity of the photographic image.

To be fair I found that the more that the image was specific, a face, a recognizable face, or an event, something already filled with pre made relationships and responses to a visual recording of an event. It was difficult to use those images. I tended to go to the very common place. Pictures of parking lots or the side of a house. Things that had nothing specific about them to pull you in. There is always a tension about the photograph and what the photograph is. In terms of its materials, shading and lighting. Various painterly concerns and then what the photograph is about.

Who is that in the picture? What’s going on? What is the picture about? Those elements fought against each other.

CG Of course those were the precise elements that were essential to your commercial work.

BF Exactly. I had very little conflict about my commercial and non commercial work. The two look absolutely different. There was no confusing them. Aside for one assignment that I absolutely loved. So it was very easy to feel that I wasn’t selling myself out. Or using things I really cared about in a way that other people had control of them.

CG Are you still using a dark room?

BF No.

CG When did that stop and you went digital?

BF Early to mid 1990s.

CG I recall you telling me that papers you had used were no longer available. A factor in the change was about availability of darkroom materials. You had papers that you drew on. You developed a part of the image and then, using the enlarger, drew or sketched out the remainder of the image. That relates to what you are doing now in terms of image sequences in which elements are removed.

BF You’re right. The more specialized and interesting the paper was away from the standard glossy and matte. There was a whole variety of papers. There was an incredible variety of papers but the more exotic they were the smaller their markets were. Before digital came into play there were a considerable number of amateur photographers.

Kodak and others decided why make this range of papers, many of them money losers, when we can make money catering to this large amateur market. We can keep one or two papers of photographic quality that fine art photographers could still use. The fine art photographers were of the least interest to those looking to make the most money from their products.

As you were talking about, the shift in journalism when subjects came to have first right of editing, when it was important to have that celebrity in your magazine. In a similar manner, all of the arts became the province of the accountants and lawyers. And not the people who had the original passions. The people who started record companies loved music and they loved the musicians. Often times they released records that they knew would never make them money.

The same is true of filmmaking. But that has changed now because of the less expensive way of making films digitally. It has attracted a whole new group of filmmakers who can make great films for very little money.

In literature the money is spent on the big money makers. There’s very little attempt if the book doesn’t catch on within the first two weeks of publication. If that doesn't happen there is little effort to promote the book and believe in that author.

The same thing is true of exhibitions. If the artist can’t carry the gallery in their first exhibition they get axed from the stable very quickly. Because the rents are so high and there is so much money to be made with the artists that are collectable. There are very few gallerists today that have the belief in their artists that Leo Castelli and gallery owners of his generation did. Early on it was a mixed bag of gallery owners and dealers who all loved art.

CG Take to me about your transition to digital. You talked about the papers being phased out. The reality is that with digital printing you can use just about any paper. Are you finding it satisfying? What are the current challenges and incentives for your work?

BF The only incentive is that for one reason or another I need to do this. The incentive is internal. There are certainly no external incentives in my life right now. I don’t have a gallery and show my work to very few gallery owners these days. For the most part it’s an unrewarding kind of experience.

The work I am doing now is far from marketable. I was never a big seller. It was very difficult for dealers to figure out what pigeon hole to put me in.

That’s exemplified by the exchange I had at MoMA. I started in the photography department and showed my work to (John) Szarkowski (1962 to 1991 curator of photography). He quickly thumbed through my work, 200 pieces in 13 seconds, and said “Why are you here? You clearly belong in the print and drawing department.” I went to the print and drawing department and they quickly went through a dozen works and said “Why are you here? You belong in the photography department.”

That’s the conundrum I’ve been dealing with for a long time now.

CG Some time ago you sent me a disc of your work. What I found most intriguing is that I’ve known your work since the 1960s. You have been kind enough to make Christmas editions from which I have some pieces.

Looking at the new works they were absolutely Benno to me. Aspects were different but their was an absolutely identifiable Benno factor. It threads through all of your work and its thinking process.

BF We don’t have to discuss how much I offered for you to make that statement. I don’t think there’s any higher complement you could have given me. Whatever I might think it states that you believe that I have been true to myself.

CG Absolutely. In a stubborn, dissident, uncanny manner. You’ve never wavered.

BF That’s the high water mark that I’ve been shooting for. That tells me that the work is mine. Which is an important issue because it’s easy, especially today for younger artists, to be seduced by the moment. Whatever is hot there seems to be a number of artists emerging who are incorporating at least a component of what that hot is. They may briefly flourish but only till five years later the heat moves on.

CG You have been very competitive as an athlete. For a time you raced motorcycles and have also been an avid skier. That has resulted in accidents and injuries. Some years ago your leg was mangled in a motorcycle accident. Then you had a severe accident while skiing from which you have had a slow and difficult recovery. Can you reflect on that aspect of your persona?

BF I’m going to have to shatter the myth and set the record straight. The leg injury occurred as the result of a photo assignment. It was for Motorcycle Magazine and the road test of a bike. It was coming toward me and veering away to get a certain shot.

I was kneeling on one knee. The rider raced in the expert class. He was the editor-in-chief of the magazine and a highly proficient rider. He was so good he thought he could get as close to me as possible and not hit me. It was the break lever or the clutch which was hanging out the side. It caught me in the hip and opened me up. I was on the pavement looking at my bone. So it wasn’t a riding accident.

The skiing accident had nothing to do with skiing although it happened while I was skiing. It could have happened slipping on the ice or any other kind of accident. I didn’t know it, but found out later, that my neck had completely calcified. It was rigid and immobile. I did know that I couldn’t use my neck very well. There was only one spot in my neck that was opened. So any force to my head would be transferred exclusively and entirely to this one spot that was still able to move between C3 and C4.

So that took the blow. It was a slow motion fall. I didn’t hit a tree. There was no blood. Nothing to show that I had even fallen. Other than the fact that I couldn’t move anything other than my eyes and mouth.

CG Give me a date.

BF February 27, 2010. I’m still and probably for the rest of my life am in recovery. Any changes and improvements now are on the nano level as anyone would perceive them. If I look back two months ago I might sense having a little more feeling in a finger.

CG Initially you were given a poor prognosis.

BF Yeah. That was because the person giving the prognosis wasn’t wise enough not to give a prognosis. The spinal cord wasn’t broken. If it were I would be Christopher Reeve part two. There’s tens of thousands of people in that situation. I was lucky only to have broken my neck and bent my spinal cord. I injured it badly but nobody really knew how much I would recover. I still take it every day at a time.

CG How are your spirits?

BF My spirits have always been pretty good. I don’t know why. There’s no reason for it. But it took a while to realize that the effect on my wife was as profound as it was on me. In a different way. I was pretty much dealing with survival for quite awhile. I couldn’t see outside myself. Not that it wasn’t there. I wasn’t even thinking about it. I was thinking about what I needed. I learned how profound the accident was in completely rocking Stephanie’s boat. Creating a protectiveness about me and a fearfulness about anything happening to me.

In fact I reinjured myself. I was reaching for something and had been doing it with a physical therapist. I shouldn’t have been doing this in my own kitchen but I was reaching for something and fell over. Trying to prevent that I fell back and hit my neck on a counter top. I broke another couple of vertebrae.

I think I finally got some sense knocked into me.

CG What is the impact of that?

BF Not much. I’m riding a bike more carefully now.

CG Come on. A motorcycle?

BF No no. A bicycle.

CG Is that a good idea?

BF Come on Charles. Reality is what you make it. Come on Charley. We’ve been there. We’ve learned something about the nature of reality. Whose reality is it? When you say ‘Is it a wise thing to do?’ Who’s talking?