Rethink! American Indian Art

Berkshire Museum Through January 6

By: Charles Giuliano - Oct 04, 2012

Rethink! American Indian Art

Berkshire Museum

Pittsfield, Mass.

Through January 6

Co-curated by Margaret Archuleta, Maria Mingalone, and Leanne Hayden

Objects from the permanent collection with contemporary works

Combining numerous objects from its permanent collection augmented by contemporary pieces by six Native American artists- Marcus Amerman, Jeremy Frey, Teri Greeves, Diego Romero, Preston Singletary and Bently Spang, the Berkshire Museum in Pittsfield has mounted the special exhibition Rethink! American Indian Art through January 6.

The museum’s staff members, Maria Mingalone, director of interpretation, and collections manager/ registrar, Leanne Hayden, worked with Margaret L. Archuleta a doctoral candidate in Art History/ Native Art History at the University of New Mexico to organize the current project.

The group of nine, three curators and six artists, met and explored the museum’s Native American collection. They worked together to create a selection, installation, response and interpretation of material augmented by new works that are inspired by tribal and craft traditions.

Particularly during its off-season programming the museum is largely focused on education. School groups and parents with children will be delighted and fascinated by this rare view of an interesting aspect of the permanent collection.

There is a full agenda of related programming including visits and lecture demonstrations by the artists. Three independent films were screened in September.

While there is much to experience and learn from this ambitious project there are complex issues.

Perhaps a way to approach the exhibition might be to take it beyond Rethink to Think Again.

It is a mandate for museums to work with their collections. There is no point in having objects that languish in storage. Projects such as this bring works to light allowing for curatorial creativity and marketing that draws visitors to the museum.

Another key consideration is that in house shows enhance the value of collections through exposure and marketing and are cost effective. Since no loans are involved that eliminates costly shipping, curatorial couriers, and additional insurance. Working with living artists and modestly scaled objects is relatively inexpensive. Particularly when travel costs are factored into programming.

On many levels the Berkshire Museum is a dinosaur. Literally. A replica of one sits outside the museum and permeates its eclectic ambiance and mandate.

The museum reflects the philosophy of its founder Zenas Crane in 1903. He was undoubtedly inspired by the Victorian era, South Kensington Museum, in London. It is known today as the Victoria and Albert Museum. Its agenda was to educate the citizens of London through the display of plaster casts of Greek and Roman sculptures, as well as, arts and crafts reflecting the British Empire. The objects and fine arts were intended to inspire the art and design of the industrial age.

Consider Pittsfield, a century ago, as the epicenter of thriving manufacturing in the many mills in the Berkshires. Other than the very wealthy, few if any middle, and working class citizens would ever see the great museums and monuments of Europe. American museums displayed replicas of European masterpieces through plaster casts and copies of Old Master paintings.

In addition to plaster replicas, still on view in Pittsfield, and some Hudson River landscapes, the mongrel museum houses specimens of natural history, a small aquarium, and collections of artifacts of anthropology and ethnographic objects.

The Native American objects that Crane acquired were often created as trade goods. Little of the material on view in this exhibition predates the mid to late 19th century.

There are issues regarding the intent and authenticity of the collection as the signage in the exhibition conveys.

Today, collections such as these have been upgraded from specimens to works of art. While contemplating baskets, pots, moccasins, war bonnets, and decorated articles of clothing we are encouraged to consider unique materials and workmanship.

An exquisitely fabricated functional object is termed an artifact. It is an object of everyday use that also may be admired for its aesthetic appeal. The artists participating in the exhibition reference those traditions but create objects primarily meant to be looked at rather than used.

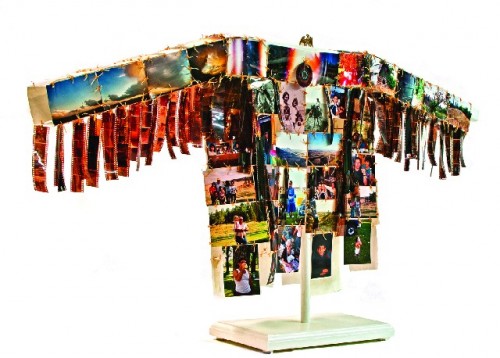

The Modern Warrior Series: War Shirt #1, 1998, by Bently Spang works as an art object. It riffs on, or deconstructs, a traditional, decorated, buckskin shirt. Fringe dangling from the outstretched arms are are fabricated from strips of exposed film rather than buckskin. The decoration of the “shirt” consists of applied snap shots. We are encouraged to compare Spang's witty takeoff to displays of traditonal decorated buckskin shirts.

This compare and contrast approach is key to appreciating the tradition-based baskets of Jeremy Frey, or the ceramics of Diego Romero.

The blown glass work Eagle Warrior by Preston Singletary conflates state of the art technology with imagery and design based on North West Coast traditions. Using molten glass it fuses old and new concepts.

Teri Greeves has fast forwarded the tradition of decorating moccasins in My Family’s Tennis Shoes Series by applying intricate bead work to sneakers. We don't know whether the elaborately decorated foot wear is meant to be seen and not worn. How utterly cool if her kids actually got to wear them to school.

When looking at the objects created by the six artists it makes us wonder whether many of the vintage objects on display were actually used. Were they functional, everyday objects, or just trade goods sold to Crane and other collectors of the period?

In the late 19th century and early 20th century the aboriginal way of life was disappearing. It needed to be documented, collected and preserved. That might be in the photographs of Edward S. Curtis (1868-1952), some are displayed here, or the dime novels of the German author Karl May (1842-1912). Fantasies of Cowboys and Indians were the pap of the silent movies and later talkies. In 1888, Albert Bierstadt painted his iconic “Last of the Buffalo.”

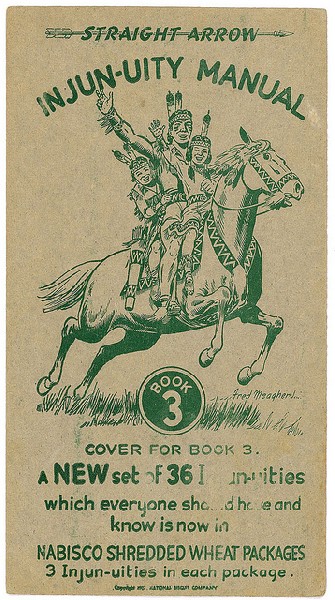

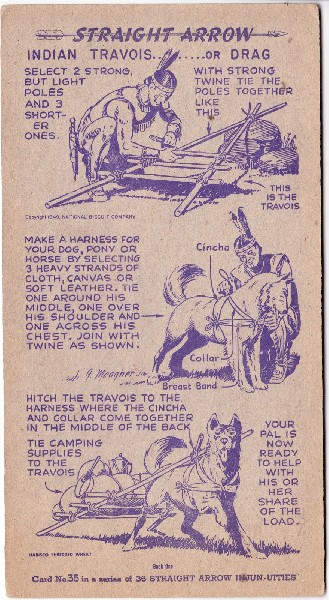

During the 1940s, I grew up listening to The Lone Ranger and Straight Arrow on the radio and reading the novels of James Fennimore Cooper (1789-1851). I collected the Straight Arrow Injun-uity cards (three to a box) that came with Nabisco Shredded Wheat.

I was more interested in the cards and their tips for survival in the wilderness than in the cereal. In fact, I hated Shredded Wheat. Still do.

A problem with the objects at the Berkshire Museum is the conundrum of extracting them from the romanticism of the era during which they were collected. Even today, the mega rich, like William I. Koch, pay fortunes to own the gun that shot Jesse James or something worn by Sitting Bull during the Battle of the Little Big Horn.

While it is productive to see the material unearthed from storage, and contextualized by contemporary, Native American artists, this Rethinking backtracks over familiar terrain.

It is a matter of proportions.

The too few examples of contemporary work are overwhelmed by the historical material of uneven interest and quality.

The six artists have been included because of their close adherence to established traditions. They contextualize the artifacts but barely hint at the scope of contemporary Native American art.

This was an occasion to provide an overview of contemporary artists, many of whom, are pushing the envelope. There are numerous example of compelling works by artists who are embedded within their cultures but embrace the mainstream of progressive art practice.

This project was initiated by the museum's former director, Stuart Chase, who has considerable experience working with contemporary Native American artists. One may only imagine how his initial vision might have taken this project in a different and more satisfactory direction.

Particularly among younger artists many strive first to be viewed as artists and secondarily as Native Americans. Being included in a show focused on traditional artifacts perpetuates reactionary thinking.

As we exit the galleries devoted to Rethink there is an adjoining gallery which leads to the permanent collection. It is often used to extend the theme of a special exhibition. In this case it was not. With a little more critical thinking and imagination this space might have provided a thumbnail of exciting developments in contemporary Native American art.

The six artists included in Rethink help us to look back on craft and traditions. A well curated sidebar would have us leaving the museum thinking about where to go from here.