Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time

Alex Sharp Brilliant as an Autistic Boy

By: Susan Hall - Oct 06, 2014

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time

By Simon Stephens

Based on the book by Mark Haddon

Directed by Marianne Elliott

Ethel Barrymore Theatre

New York, New York

October 4, 2014 through March 31, 2015

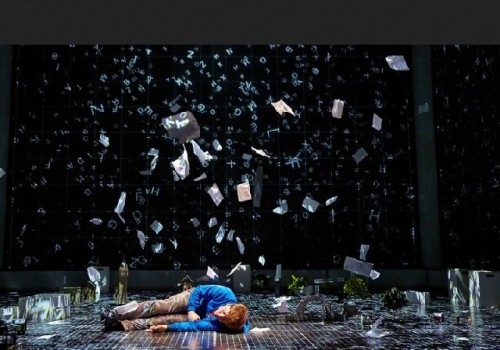

The stage presentation of The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time is smashing. Lights dance and Christopher, a fifteen year old autistic boy, walks at a ninety degree angle on a wall. Later, we will learn that he understands well what creates this angle. He is intellectually curious and appears to be master of more than the Pythagorean fomula. Unfortunately, he does not display a deep knowledge of the Bayes Theorem.

Christopher is played magnificently by a recent graduate of the Julliard school, Alex Sharp. Leaving the presumed comfort zone of his immediate family, he becomes a detective in search of the murderer of his neighbor’s dog.

Visually, the dog plunged with a pitchfork is an arresting image to open the play. Christopher’s mother has ‘died’ and his father is now in charge. He is a kindly man who clearly loves his son and wants to do right by him. Ian Barford gives a solid performance in this role. When, however, he appears in a balcony representing distance from Christopher, the concept does not work.

In the London production, the audience was kept as close to the center of the action and the curious workings of Christopher’s mind as possible. At the Barrymore in New York, the proscenium stage by its nature keeps the audience away. Whether or not a closer embrace would have changed the play’s presentation can’t be answered.

This is because, in the London production, Christopher was at risk the moment he left his home as a detective. In New York, the only moments that create this sense of risk occur in the second act when Christopher dives onto an Underground track to rescue his pet rat Toby and is almost run over by an oncoming train.

The three principals in this story, which begins in “once upon a time” read from the book which underlies the play, are the autistic boy and his parents.

The mother does not appear until the second act, and her role is not as strong or clear as the father’s. What pleases is the fact that she is not blamed for having difficulty caring for an autistic child, a super difficult task at best. Her role is muddled and Enid Graham has difficulty making sense of it. The director does not help.

Marianne Elliott, who won much acclaim for her direction of War Horse, is at the helm. She is a master of effects. No one can blame producers for adopting LePage’s tools in an effort to bring striking visuals to an audience which is daily assaulted by them in every way. But these tools should be in the service of a story and its characters.

The problem here is that we are left feeling that the visuals and characters are empty. The stage is full of glitter and dancing images. In the end the characters are hollow.

The twists and turns of the autistic mind and experience are beautifully expressed in the language of the play. They are delivered by Sharp in a thoroughly engaging style. But they do not transmit to actors carrying boxes all over the set. The father’s love is very real, but the teacher who guides Christopher to his math exam is sketched only in outline.

While this may be an effort to create how characters impact on Christopher’s mind, it would be a misunderstanding of autism to think that he does not feel, even though his expression of emotion is unfamiliar to most of us.

The play is curiously unsatisfying in the end, because it is hollow, in spite of all the glitz.