Karole Armitage at Mass MoCA

Annual Co Production of a Dance Company with Jacob's Pillow

By: Charles Giuliano - Oct 08, 2007

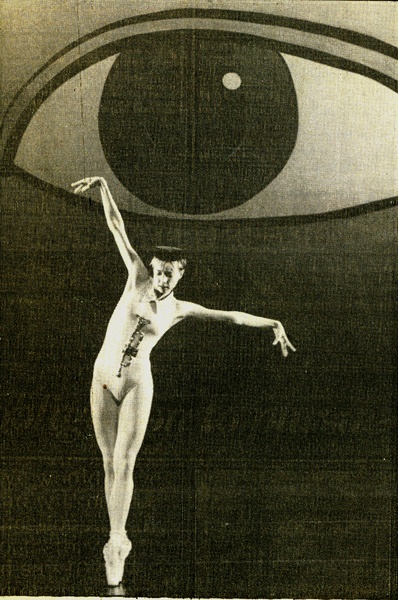

Ligeti Essays (2007)

Music by Gyorgy Ligeti (1923-2006). Choreography: Karole Armitage. Set Design: David Salle. Costume Design: Peter Speliopoulas.

Lighting Design: Clifton Taylor

Time Is the Echo of an Axe Within a Wood (2004-2006)

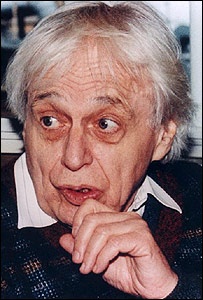

Music: Bela Bartok (1881-1945), Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta. Choreography: Karole Armitage. Set Design: David Salle and Clifton Taylor. Costume Design: Peter Speilopoulos

Dancers: Leonides D. Arpon, Matthew Branham, Frances Chiaverini, Theresa Ruth Howard, William Isaac, Ryan Kelly, Mei-Hua Wang

Armitage Gone ! Dance

Co Presented by Jacobs Pillow at Mass MoCA, Sunday, October 4, at 4 PM.

http://www.armitagegonedance.org/

It has become a wonderful tradition for Jacob's Pillow, which ends its season in late August, to offer an early October collaboration with the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art. There is an appropriate synergy in the two Berkshire based cultural institutions with a common mandate to present new works by leading contemporary artists and choreographers. Ella Baff, the artistic director of Jacob's Pillow, also serves as a board member at Mass MoCA. As a part of the format in these annual events Baff engages in a critical dialogue with the choreographers which delve into the works presented and allows for questions and comments from the audience. These discussions are particularly helpful, as was the case yesterday, in gaining insight to difficult and demanding new works such as the two pieces "Ligeti Essays" and "Time Is the Echo of an Axe Within a Wood."

A considerable time had lapsed since I saw her work on one other occasion, in November, 1986, during an exhibition by the painter, David Salle, at Boston's Institute of Contemporary Art. His show included drawings for sets created for her dances. The ICA sponsored event allowed for presenting that aspect of design for dance. The ICA sponsored the premiere of a three act ballet "The Elizabethan Phrasing of the Late Albert Ayler." At that time Salle's sets, they were then married, were rather literally his paintings in front of which her company danced. The Albert Ayler (1936-1970) piece, inspired by an avant-garde jazz saxophonist who committed suicide, was her second collaboration with Salle. Their first was "Mollino Room" for the American Ballet Theatre. She has also worked with the artist Jeff Koons.

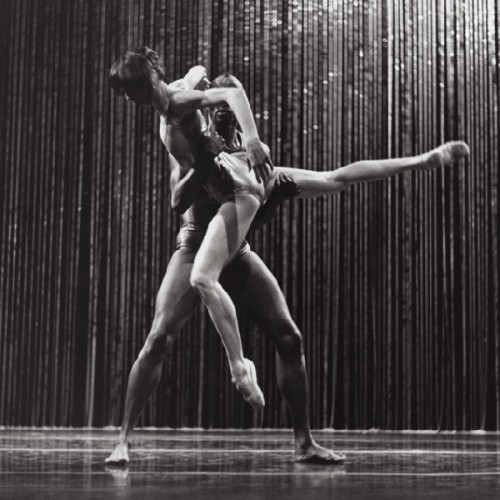

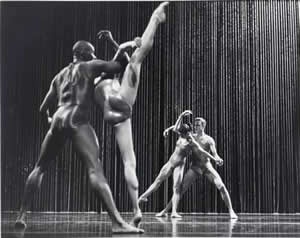

During yesterday's performance it was evident that she, as a choreographer, and Salle, with whom she still works, have come a long way. The program credited him as the "designer" of "Ligeti Essays" but his presence and contribution were somewhat invisible as the dance was presented in what appeared to be a black cube accented by the subtle lighting of Clifton Taylor. There was a thick, white, taped line marking off a square on the stage floor. In "Time Is the Echo of an Axe Within a Wood" Salle's set design appears to be a beaded curtain from edge to edge at the back of the stage, accented by the lighting of Taylor. Initially the beaded curtain reads like a relief because of a sharp angle of the horizontal light. This changed to frontal lighting and it became apparent that it was meant as a curtain through which the dancers at intervals in varying solos, pairs, quartets and ensembles entered and exited. At one point there was a dramatic effect as a rapidly exiting dancer, behind the curtain, extended an arm along it creating a ripple.

The entrances and exits of the dancers was a key element of both works which had similarities in their evocation of time, rhythm and percussion, changing tempi and the sense of dream and reverie. There was a lot of play with the physical differences of the company in terms of the gender, race, height and physical mass of the individuals, their characters and personas. The most commanding presence is the enormously powerful and smoldering William Isaac a native of Antigua. For contrast he often paired with the small and slender Mei-Hua Wang a native of Taiwan. The most riveting female dancer was the tall and plastic Frances Chiaverini who was occasionally featured solo and created angular, complex and precise configurations, often quite contortionist. Chiaverini of all of the dancers most seems to be a surrogate, physically and emotionally, for Armitage who was not present on stage.

As has become a norm in contemporary dance there was same sex partnering as well as an emphasis on racial disparity. Leonides D. Arpon, a diminutive and compact Filipino man was coupled with other male dancers seeming to take on feminine roles in the quasi traditional lifts. Theresa Ruth Howard is a large and muscular African American dancer who in body type and style contrasted dramatically with the other two women. There was a daunting physical presence and concentrated grace to her movement. Having such off kilter partnering it was almost a surprise when we saw a "traditional" same race pairing of Howard and Isaac or Wang with Arpon.

One felt in a way that Armitage was tweaking us by combining aspects of traditional dance and ballet with her own inventive amalgam of modernism. One style and tradition seemed effortlessly to elide with another. While there was difficulty identifying the canon of her movements there was little doubt that its discipline and precision are rooted in her training, first with the more classical Balanchine company, and then with the avant-garde master, Merce Cunningham.

During the dialogue with Baff she was asked if the movements had specific names and how they were conveyed and taught to the company? She responded with some whimsy that yes she had names they made up to convey specific steps often are given the names of the dancers who best execute them or for a bird or some other reference. She described traditional dance moves as exploring vertical and horizontal vectors but that she was seeking to explore the diagonals as well as imagined circles around the dancers. There is definitely a signature look to her choreography but it is difficult to articulate its exact elements as she is inventing a new vocabulary of movement which has both absorbed all that has preceded her while seeking new possibilities.

Asked about how the pieces evolve Armitage described how it always starts with the music. When the choreography is evolved to the point where it is presented to the company there are adjustments in how the dancers react to and interpret what is presented to them. The company in the studio may take several months to refine and learn the piece. But once a dance is developed it requires just several days of rehearsal to put it back into the performance repertoire. Part of that process is allowing time for the dancers to develop the conditioning and stamina to execute the physically demanding movement.

The question was posed as to whether she commissions music from living composers. With humor she stated that she preferred "dead ones." And that she does not have the financial resources to commission composers on the level of the great masters and inspiring pieces such as the Ligeti and Bartok works in the current program. She also stated that there is too little understanding of dance and that a commissioned composer might make music that is too literally adapted to their notion of what dance might entail or require. It is better to select the music and work from there.

Mostly I sense an austerity in the work particularly the demanding music and choreography of the "Ligeti Essays." The music combined voice, solo and ensemble, and a range of percussion. Some passages evoke traditional Hungarian dances while there was a moment that sounded like Kabuki. Although there was song none of the text was recognizable and though inspired by the poetry of Sandor Weores there was no way to understand the meaning of the words. So the voice became an abstract instrument like the vocalese or scat of a jazz singer. For me, the voice was just a sound and there was a struggle to understand how the text and poetry related to the movement. I asked her about that and she responded that the lyrics are sung in Hungarian and that she had studied the texts, in order to understand and interpret them, in the process of framing the dance. One wondered if the experience would be different for an audience fluent in Hungarian or familiar with the poetry. It would have helped to have program notes on the poetry or perhaps a translation.

Armitage discussed how the two works are related and that she is working on a third piece to form a kind of trilogy of dreams. She discussed that there are incidents and attitudes in the interactions of the dancers but no attempt at a narrative in the usual sense. The Bartok piece is moody and evocative and the dance seemed quite specific in interpreting its power, dynamic shifts, and dramatic use of percussion. At times the ensemble work was so frenetic that it must be exhausting to execute.

One wants to use the term minimalist to describe her choreography and staging but perhaps a better work is sparing. The music and mood is not minimalist as one would apply the term to Steve Reich, Lamont Young, or Philip Glass. The music of Ligeti, who composed for the films "2001: A Space Odyssey" "The Shining" and "Eyes Wide Shut" was surely avant-garde but not minimalist. Ligeti shared an interest in rhythm, time signatures, and percussion with the minimalists.

With some humor and a bit of apology Armitage compared her style and approach to dining in Tuscany. She lived and worked for several years in Florence and has only recently returned to New York and been able to sustain her own company. "It's like eating in Tuscany," she explained. "The food involves few ingredients but very precisely selected and prepared. I hate to keep using that analogy but it's true."

Her dance involves just a few elements but, like those Tuscan chefs, combined with superb restraint. It is difficult, demanding and complex work that has an audience working hard to keep up. Nothing is simplified or broken down. She really wants us to feel and understand the music but the dance is never overly literal or descriptive. It is best to say that the dance is performed in parallel to the music as a separate but related entity. Well, perhaps, it is an acquired taste but if you have a sensitive palate, quite delicious. Truly a feast of movement for the eye.