Big, Bold, and Undeniably Ambitious

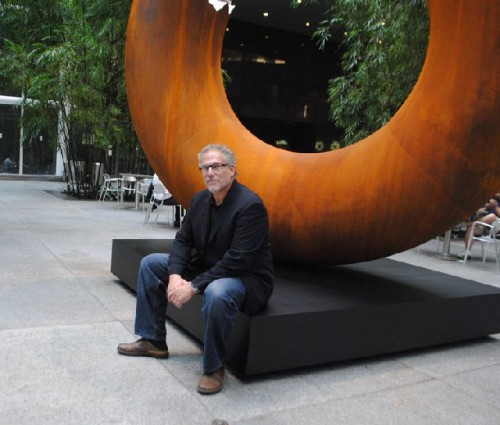

Jonathan Prince at the Sculpture Garden in New York City

By: Edward Rubin - Oct 18, 2011

The work of Massachusetts based artist Jonathan Prince, currently on view till November 18 at the Sculpture Garden in the atrium of the old IBM building in New York City under the title Torn Steel, like the artist himself who resembles Julian Schnabel, is big, bold and undeniably ambitious. But underneath the swagger of the man and his work – this based on an in-depth studio visit, a couple of wide-ranging conversations of the inquiring kind, and of course the four, eye to mind-grabbing, sculptures on view – lives a sensitive soul, albeit it on top of a simmering volcano, whose innards house an acute and restless intellect that appears to know no bounds.

Though relatively new to the art world, that is, as a full time practitioner – Prince has only been sculpting 24/7 for the past eight years, a somewhat unbelievable fact given the sure footedness of his work – as a young boy he was drafted into the world of art through a series of visits with his father to the studio of artist Jacques Lipchitz. It was here that he was first exposed to contemporary art, to Lipchitz’s extensive collection of pre-Columbian sculpture, and experienced first hand – with a few demonstrations by the master himself – of what it means to be an artist.

As a teenager, still smitten with the lesson of Lipchitz, Prince turned both hands to sculpting in stone, clay, as well as plaster. As fate would have it – following in his father’s footsteps like a good son – his trajectory led him to the art of dentistry and maxillofacial surgery. After three years in this highly precisioned eye to hand occupation, Prince turned to directing and producing films and computer animated special effects projects. After successfully embracing the art and science of filmmaking for a number of decades, he returned – an argument could be made that he never left it –to his first love, that of sculpting.

In Torn Steel, his newest series, Prince, known primarily for his work in black granite, stone, and marble, each harboring traces of Noguchi, Brancusi and Arp, uses steel, oxidized and stainless, to implement his vision. “Steel is less tight than stone. It gives me the opportunity to cut something or to weld it back,” he told one interviewer. “What I’m hoping to create is the intersection between chaos theory and refined geometry.” True to his word, the artist’s four geometrically shaped works, set down among the atrium’s elegant stand of bamboo trees – the cellular softness of nature embraces our industrial civilization – does just that.

At first glance, Prince’s monumental sculptures appear to be nothing more than simple geometric forms, a square with a broken edge, a column with its top gouged, and couple of circular sculptural riffs, one resembling a large distressed pill set on edge, the other a partially eaten donut doing a clever balancing act. On closer examination the lively quartette begins to take on an otherworldly, if not quasi-religious cast. We ask ourselves, refraining from the act of praying, are these objects relics of worship from a lost civilization, artifacts left behind by a race that died off, a Hollywood studio props leftover from some Roman epic, or are they really post-modern sculptures waiting to be transported to some city plaza.

Though each sculpture, massive in appearance but deceptively hollow in actuality is simply dressed in its mostly oxidized appearance the labor intensive process to get them there is anything but. It all begins with Prince sketching out a concept. After refining it on the computer, he creates a urethane foam model, along with a series of engineering drawings which enable him to order the necessary materials for fabrication. Once the full geometrically shaped work is constructed the artist marks the sections to be “torn” out from the sculpture with a plasma cutter. Then the stainless steel plates are shaped, welded into the form, the patterns are overlaid onto the plates with a MIG welder in stainless steel, and all areas smoothed and blended with a TIG welder. Finally, the stainless steel areas are smoothed and polished with various abrasives.

The most satisfying and easily digestible of the four sculptures on view – also the most challenging in its simplicity – is Vestigial Block, Prince’s six foot square cube. It is here at the 6 x 6 x 6 foot cube, unfettered and uncomplicated by the distracting jagged cuts and molten steel plating found at the top of Totem, at the two ends of Torus, and the decoratively placed distressed cuts on the sides of Disc Fragment – though inevitable given Prince’s concept – that Prince’s technique of exposing the soft molten innards buried within the sculpture’s hard outer shell appears at its least forced and most natural. It is also at this stop, while basking gently in light of this daringly modest sculpture, that our mind is gently seduced into conjuring up images of the earth’s fiery center, overflowing lava, and thoughts the human body housing an active soul.

Note: The Torn Steel exhibition at the Sculpture Garden at 590 Madison Avenue and 57th Street, New York City, runs through November 18, 2011. For those unable to make it to the exhibition a beautiful video filmed during the exhibition’s installation with Ghostland Observatory singing Sad Sad City from their 2006 Paparazzi Lightning Album in the background, will put you front and center. http://youtu.be/JtFQnQc-b0g