Covert Operations: Investigating the Known Unknowns

Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art to January 15

By: Charles Giuliano - Oct 18, 2014

“[T]here are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don’t know we don't know.” —Donald Rumsfeld, 2002

Through January 15 the entire Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, comprising three large galleries in a former movie theater, have been painted black to present a single stark, compelling and brilliant special exhibition Covert Operations Investigating the Known Unknowns.

Arriving for our first visit to the museum in an attractive complex of performing arts, library and themed mall, Astrid recognized SMoCA director, Tim Rodgers, from a thumbnail on the museum’s website.

Having introduced ourselves we were invited to join him for a tour of the riveting exhibition with three of his friends. Rodgers proved to be an engaging and passionate guide.

Returning post tour with press materials we asked Rodgers how the exhibition had come about. Frankly, it was a pleasant surprise to encounter such an ambitious project in a small rural museum. Particularly in socially and politically conservative Arizona. This is the home state of Barry Goldwater and that legacy continues today with hot button responses to a vulnerable border resulting in security breaches caused by an overwhelming influx of undocumented immigrants.

As Rodgers explained that’s precisely why the project has been supported as one of three, annual exhibition grants from the Tremaine Foundation. The funding allowed for an exhibition that exceeds the budget for the fifteen-year-old museum which gets half of its operating revenue from the city of Scottsdale. The museum is acquiring a permanent collection stored in the vast, adjoining performing arts center.

When asked how the museum had initiated this exhibition Rodgers had a surprising response.

It seems that the former art history professor, who has been with the museum for five years, was asked to speak to a local group. They proved to be now retired members of the CIA. He recalled that the museum’s curator, Claire C. Carter, had revealed to him that as an undergraduate she was approached by CIA recruiters. He invited her to join him for the talk.

After which there was no evident response. Other than polite applause there were no questions. But during the following reception he was approached by individuals anxious to discuss their insights.

He was intrigued by the spy-like behavior. On the drive home he told Carter that they may well have stumbled upon a great theme for an exhibition. It seems that once retired, because of the rapid turnover of intel and technology, many are unrestricted to discuss their time with the Agency. Not just field agents many were formerly involved in developing surveillance technologies much of which is manufactured in Arizona. In the book shop of the museum was a small and fascinating display of surveillance devices, vintage and contemporary, sold by the local spy shop.

In order to acquire a liquor license for the museum Rodgers went to the shop which does fingerprinting, as well as sell guns, ammo and spy stuff.

That says a lot about Arizona and the Wild West where it's OK openly to pack heat.

As part of the programming for the exhibition the museum hosted a Dinner with a Spy benefit. There was one former agent at each table. According to Rodgers the guests got an earful.

After considerable research, development and grant writing Carter selected some 35 works by a diverse group of American and international artists: Ahmed Basiony, Thomas Demand, Hasan Elahi, Electronic Disturbance Theatre 2.0 (a group of artists), Harun Farocki, David Gurman, Jenny Holzer, Trevor Paglen, Anne-Marie Schleiner and Luis Hernandez Gakvan, Taryn Simon, David Taylor and Kerry Tribe.

While inspired by the Kafkaesque, Dr. Strangelove quote from Donald Rumsfeld, only a single work by Holzer refers directly to 9/11. It is a blown up, redacted document obtained through the freedom of information act. It refers to an ignored report of a known suspect receiving flight instruction in Arizona. The report was buried in masses of acquired data. That individual was one of the pilots who brought down the World Trade Center towers.

Entering the exhibition one encounters thirteen “ribs” by Holzer over which scroll autopsy reports on suspected terrorists who died as American captives.

The black box approach of the installation design enhances some works, particularly video displays and a projection booth, but not photographs and graphic displays of varying dimensions. More variety in the separate galleries might better have enhanced the ability to absorb dense and diverse works.

Other than Holzer the artists on view were unfamiliar. Collectively they enforce the notion that great minds think alike. With no direct connections they explored common concerns about surveillance and privacy enacted by the sea change of post 9/11 Homeland Security and erosion both subtle and not of Constitutional guarantees of human rights and freedom.

This Orwellian debate between national security and erosion of privacy is of course nothing new. It is just more pervasive and abundantly evident. Like warning a friend that you don’t want to participate in radical discussions over the phone or by internet.

Indeed Big Brother is watching.

Holzer’s “Phoenix yellow white (detail)” is an example of the glut of raw intel that routinely remains unprocessed through a lack of trained analysts. Just what are the FBI and CIA doing with all of our e mail and cell phone data?

The Bangladesh born, American artist Hasan Elahi, turned the tables when caught up by misguided profiling. Returning from a trip abroad he was nabbed by the FBI in June, 2002. He had been observed and reported for leaving “explosives,” actually artist’s materials, in a Florida locker.

That landed him on a terrorists watchlist. It resulted in several days of interrogation as well as multiple lie detector tests. Even though he is clearly not a bad guy he continues on the no fly list. He remains under surveillance and must request permission every time he boards an airplane.

Clearly artists, as demonstrated by this probing exhibition, are a real threat to national security.

In the ongoing now twelve years of his active “Tracking Transience” on line Elahi invites us to view his live GPS location. He takes thousands of posted images of his daily meals, bathroom visits, travel and other mundane gluts of information. It is a metaphor for the notion that this overload of data, without interpretation, reveals nothing about him or his all important thought process. The bottom line of the work evokes a numbing and chilling impact.

The work of David Taylor has a particular relevance to an Arizona audience. He had sustained access to patrols along the Mexican border. Because of inadequate budgets outdated technology assures misinformation. That infamous fence has an end which he photographed. It is absurdly obvious by tire tracks that smugglers toss contraband around the fence which is then picked up and driven off.

It enforces the truism of show me a 12’ fence and I’ll show you a 13’ ladder.

The initially benign photographs of Taryn Simon raise the issue of access to seemingly secure places. One is a corridor at Langley showing abstract art “protected” by a stanchion. Another reveals exposed and easily corrupted trans Atlantic cables. If an artist can get that close to sensitive locations what does that say about the access of bad guys?

The generic photograph of a compact kitchen by Thomas Demand evokes no initial response. We learn that he reproduced and photographed what proves to be a replica of Saddam Hussein’s last bunker where he prepared a final meal before being captured. There were sensational images of the bearded fugitive dragged from his lair. To highlight that event Demand has focused on a thought provoking view of the mundane daily life of an on the run former dictator.

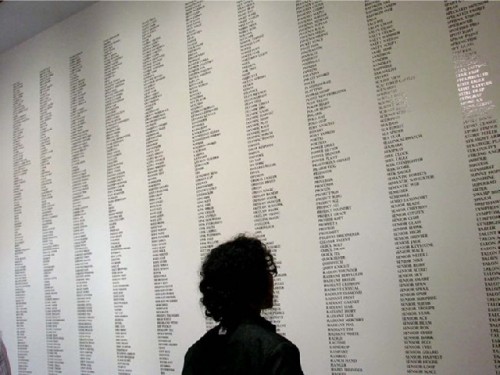

Along a wide expanse of walls are columns of what prove to be endless code names for covert operations. Trevor Paglen is playing a name game with viewers. What you see is not what you get. He also displays several decorative shoulder patches for these covert organizations.

Memorial for the New American Century by David Gurman entails a loud bell that on the hour strikes for each recorded death that day in Afghanistan. The work, which is being acquired by the museum, is powerful but overwhelming. Its cycle of rings makes it difficult to focus on other works. While noting the metaphor it was a relief to again enjoy silence. It tended to put a visitor on the clock to finish viewing the exhibition before it started again. It is a response we have had in group exhibitions where the volume of one artist’s work drowns out the response to the efforts of other artists.

Perhaps the curator might have considered another location for the piece.

For Untitled (Potential Terrorist) a 30 minute, looped, black and white film Kerry Tribe put out a casting call. Watching in a small booth it is uncanny that the silent actors convincingly convey the look, gestures and persona of bad guys. All too readily it conveys how racial profiling configures innocent individuals into potential evil doers. It signifies the dark side of America where anyone of Middle Eastern or Islamic heritage falls under suspicion.

The split screen videos of Harun Farocki present an army training video in the form of an interactive game flanked by young soldiers learning how to respond to threats in the field. There is the spooky realization that kids growing up on violent video games are eliding unique skills into combat situations. Arguably, for these young warriors it conveys the notion that war is just another game. But a far more dangerous one with life threatening situations.

Ahmed Basiony was a participant in the Egyptian protests during the Arab Spring. He was struck in the face and neck by rubber bullets in Tahrir Square. His cell phone with intense and frenzied live footage was posthumously intercut and edited with his conceptual work. With elaborate gear he recorded daily body responses to intensive, hour long sessions of running in place. The combined work is a metaphor for the futility of what, at the moment, seemed like a movement of hope and change.

We left the exhibition full of riveting and provocative insights. In today's art world that's saying a lot. Interesting that you have to get off the main drag to find such original and compelling work.

This feisty show rightly puts Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art on the map.