Istanbul Biennial

A Vast Platform of Art in a Wondrous City

By: Zeren Earls - Oct 19, 2015

In its 14th edition, the Istanbul Biennial features over eighty artists from every continent in 36 venues throughout the city. Saltwater is the theme for 1500 artworks, comprising paintings, drawings, sculptures, installations, and media art, and spreading from the northern Bosporus at the edge of the Black Sea to the Princes’ Islands south of the city in the Sea of Marmara. Venues include museums and temporary spaces on land and on sea, such as boats, hotel rooms, former banks, garages, gardens, schools, shops, private homes, and even a hamam.

Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, the “draftsperson"– her choice of word for “curator"– of the Biennial, offers a multi-layered metaphor for delving into historic tides and waves of humanity, based on the theme “Saltwater: a theory of Thought Forms". She encourages consideration of the corrosive nature of salt as a material, along with the contrasting image-forms of knots and waves of the seas, underscoring the flow of people across the world. Istanbul’s history and location provides a good setting for an exhibition surrounding saltwater.

My four-day journey began in Büyük Ada, the largest of the four Princes’ Islands, home to horse-drawn carriages and 19th-century mansions for summer residents. After a 40-minute boat ride on a beautiful autumn day, I reached the island, which hosts six of the Biennial venues. Nearest to the boat landing is the sea bus Kaptan Pasha, on which can be found Saltwater Heart, a sculptural installation consisting of a mesh of clear tubes in the shape of a heart. Pinar Yoldas explores the themes of pollution and nature with seawater flowing through the tubes at the rate of a whale’s heartbeat, conveying the message that “when the pump we call the heart stops, life ends.” Covered with felt in the bowels of the ship is a submerged universe by Marcos Lutyens, where a skeletal frame of a vessel in the Sea of Marmara emits light and color.

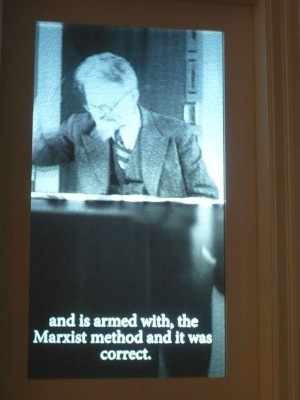

The Splendid Palace hotel, built in 1908 in Art Nouveau style, is the perfect venue for South African artist William Kentridge’s Sentimental Machine, a five-channel video installation. Based on information on Leon Trotsky’s exile on the island from 1929 to 1933, we hear conversations behind closed doors and see Trotsky sending and receiving letters and giving speeches about revolution in black-and-white images projected from behind frosted windows. Eventually Trotsky is submerged by waves, along with his thought that the human is a sentimental but programmable machine; thus ends his utopian thinking.

The Mizzi Mansion, built in the late 19thcentury as a private residence with high ceilings, provides a unique architectural setting for the sounds of underwater recordings and beacons from around Istanbul in Susan Philipsz’s installation Elettra. Inspired by Marconi, who said “Every sound we ever make is still out there. Once generated, it fades but never goes away completely,” the memorable sound installation is enhanced by a display of the artist’s large photographic prints of the remains of Marconi’s ship, the Elettra.

A path winding down to the sea leads to the wrecked shell of Trotsky’s house, where the writer lived for two years at the end of his four-year exile from Russia. The facade, still standing tall amidst a lush garden, bespeaks a bygone era, encouraging further exploration down the uneven path. An iron gate, which opens to the sea, frames an unexpected yet delightful view of two gleaming white giraffes enticing the visitor to enter. Just off the waterfront, a bestiary of animals stands on plinths like chimeras in the sea. The arresting site-specific installation, The Most Beautiful of All Mothers by Adrián Villar Rojas, includes a gorilla with a stone lion perched on its back, a rhino with a heavy load of amphora, a sheep laden with fishnets tangled with seashells, as well as driftwood, an ostrich wearing a coat of brushwood, an elephant, a camel, goats, and horses, all burdened with loads mostly found at sea. The life-size fibreglass animals gaze at the house to haunt or reclaim the land.

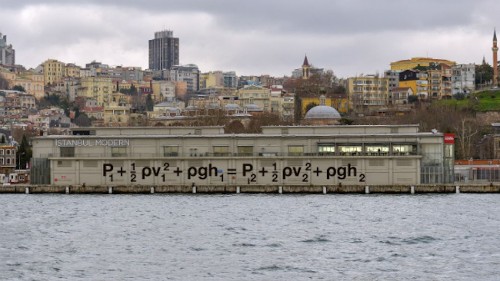

On the second day, another boat ride took me to the Galata Pier, where Istanbul Modern, the city’s contemporary museum is located in a former cargo warehouse on the Bosporus. Seen from the boat, the museum’s facade features Liam Gillick’s wall painting, Hydrodynamica Applied, depicting the Bernoulli equation–as pressure decreases, speed increases.

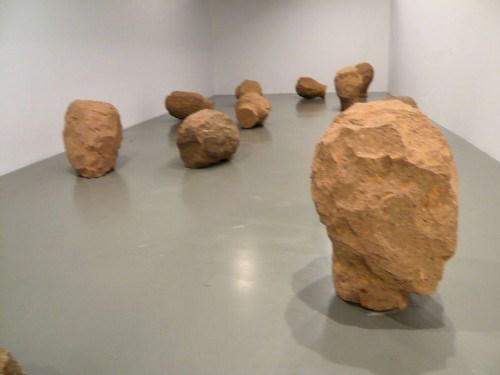

Inside the museum are exhibits by 55 artists responding to various sub-themes. A frequently recurring one is the100th anniversary of the deportation of Armenians during the Ottoman Empire. Silence of Stones by Sonia Balassarian, an Iranian artist of Armenian descent, consists of twelve large heads roughly hewn from tufa stone. Found on the Armenian side of the border with Turkey near the city of Ani, the stones, though silent, speak of memories born in grief.

Another story of loss in the history of Armenia appears in Asli Çavusoglu’s Red/Red, consisting of paintings and notebooks handmade from worn paper. These narrate the story of a red pigment traditionally made by extracting the color from an insect known as the Ararat cochineal, using a formula which has now been forgotten. The artist paints this loss through a transition from a deep carmine pigment to the bright red of the Turkish flag; while the latter endures the former fades.

Sarkis, born in Istanbul of Armenian parents, has 51 photo-collages from the collection of the Museum of Collages in Paris. Truth, image-making, and the function of photography as a political act all fold into a display of images from life. In the modernist abstract paintings of Lebanese Paul Guiragossian (1925-1995), bands of adjacent color and a multiplicity of stripes become a metaphor for a series of individuals or a cohesive group deported.

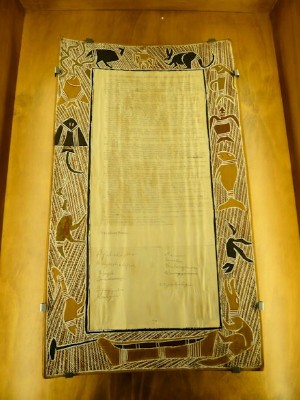

The sub-theme of human struggle extends to the indigenous people of Australia. Among the highlights of the Biennial are bark paintings by aboriginal artists used as maps and as messages for the restoration of land rights. Saltwater paintings refer to struggles to gain sea rights. Yolngu artists used such paintings as evidence to prove their knowledge and rights over waters near their lands. Vernon Ah Kee uses the canvas to reflect his anger about Brutalities and Lynching.

The Pillar series by Marwan Rechmaoui is a strong reminder of our turbulent times. The Lebanese artist has erected concrete pillars embedded with traces of residential buildings, giving the appearance of a bombed-out row of apartments. The towers have crumbled, but are still standing. Nikita Kadari of Ukraine constructs as his surroundings are destroyed. His installation, Shelter, is a two-story unit – taxidermy above, bunks with growing vegetables below.

Anti-capitalist sentiments are raised in Grace Schwindt’s Little Birds and a Demon – a Still Life, which features a room furnished with carpets made of coarse sea salt, an antique dining table, and chairs. On the table is a copper cauldron with a ladle to serve used-pointe-ballet-shoe soup, along with bowls and silver spoons. The shoes are cut up for easy consumption. From the speakers, an operatic voice sings of the Northern Sea Route that cuts across the Arctic waters to connect the oceans, questioning the capitalist fantasy of free access and connectedness in moving goods across the globe, without consideration of disastrous economic and social implications.

Venus of the Rags by Michelangelo Pistoletto, puzzling at first, brings on a smile upon contemplation. The work, created in 1967, is a plaster cast of Venus combined with a vibrant pile of rags. We see Venus only from the back. Here high art enters ordinary life, as energies are collectively shared and combined.

The Galata Greek Primary School, a neo-classical building from 1909 constructed for the education of Greek children in Istanbul, has been closed since 1988 due to the decrease in the Greek population. Its spacious exhibition space on the first floor features Salt Traders by Egyptian artist Anna Boghiguian, with sails hanging from the ceiling, exploring the nature, history, and science of salt from scientific formulas and maps of the world, which decorate the draped sails, along with a floor display of piles of salt from Ethiopia, Pakistan, and Turkey. The sculptural space and sound tell the story of the reemergence in the year 2300 of a boat carrying salt that was lost in ancient times in Antarctica and reappears when the ice caps melt. The world rediscovers its past from this boat, at a time when the digital era no longer exists, corroded by salt and oxidation.

In the upstairs galleries, Michael Rakowitz connects the Armenian history of Istanbul to the Turkish saying “The flesh is yours, the bones are ours” in his eponymous project. The saying refers to the influence that a teacher is granted over a student by the student’s family. The city’s Art Nouveau buildings rose at a time when its Armenian population was declining. Artisan Garabet Cezayirliyan crafted the moldings and friezes on the facades of these edifices, many of which are still visible. Rakowitz replicates these molds by using an old tradition of mixing ground bones in plaster, opening up the larger question of the maintenance of tradition as a resistance to cultural erasure. Another component of the project is based on rubbings from the facades – the skins – of buildings, conjuring up “an urban ‘séance’ for the ghosts of forgotten citizens.”

The Open School is a program directed by Hera Büyüktasçiyan. The program notes read: “At the Greek School, there are no more students; yet people gather and read together.”

The following two days were an adventure through the well-worn streets of Istanbul. I began in the Karaköy district, at the Kasa Gallery in Minerva Han, a landmark constructed in 1923 as the Bank of Athens. The vault of the former bank, now part of Sabanci University, is used as an exhibition space. Walid Raad’s installation, Another Letter to the Reader, recalls a time during World War I when famed Iznik tiles were crated and sent to bank vaults for safekeeping and to guard the motifs, but were later found to have been stolen. Raad’s stacked packing boxes and wooden shipping crates laser-cut with Ottoman tile motifs raise the question, “Can you ever hoard and store a motif?”

Another former bank, dating from 1863, is now in its fourth reincarnation as the House Hotel on Bankalar Avenue. Its vault is home to a marionette show, Sad Waltz and the Dancer who couldn’t Dance, staged by Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller. The story is based on an imagined craftsman making puppets in a small room in this hotel. A robotic marionette pianist plays a very sad waltz, while the dancing marionette keeps falling because the puppet maker is no longer there – a beautifully staged four-minute performance.

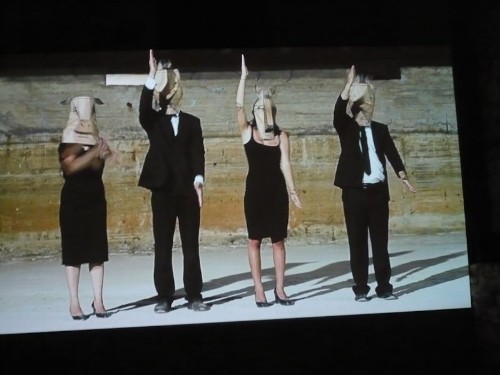

A cistern dating back centuries in the Adahan Hotel is the stage for The Fall of Artists’ Republic, Episode 2 of the 2084 science fiction video by Pelin Tan and Anton Vidokle. Four actors wearing masks discuss their artist-run republic and its subsequent fall due to the relentless endeavor to transform life into art. States are ungovernable; museums are data centers; money is abolished; there is no more work.

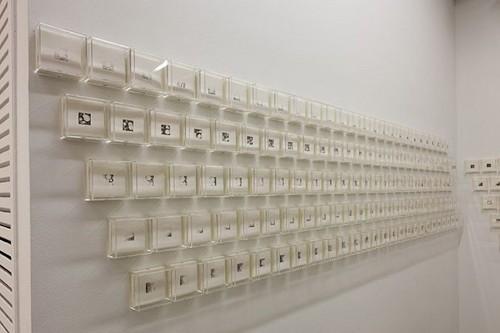

ARTER on Istiklal Avenue is a renovated 1910 building currently run as an art house by a private foundation. Christine Taylor Patten, one of several artists exhibiting in this space, explores the infinite possibilities of the line using crow quill and ink on paper. Micro/Macro 1001 Drawings is part of a larger collection of 2001 1x1-inch works created from 1998 to 2015. The tiny drawings unfold from a single dot and grow into irregular organic wave patterns.

The Italian High School in Beyoglu is in a neo-classical masonry building dating from 1919. The multi-story building is home to works by six artists, including Cheng Ran from Inner Mongolia, who has a 9-hour Film shot in Tibet, the East China Sea, and the Netherlands about missing people.

Theaster Gates has a street-level pottery shop, which is part of a larger complex built in the early 1940s in Tophane. His project, Three or Four Shades of Blues, is about art, daily life, and the importance of transmitting skilled artistic crafts. People come and go, making pottery together while listening to albums from Atlantic Records, founded by Turkish musician Ahmet Ertegun. A rare Iznik bowl is on display in the shop as a reminder of high craft.

Deniz Gül’s installation, Stone (Manuscripts Don’t Burn), occupies a room in a derelict house dating from 1915. The old ceiling is covered with an interior sky carved of linden wood and marked with signs conveying the hope and loss of Anatolian civilizations. Floor mats encourage the visitor to lie down and look upwards to dream.

Such Prophecies We Write on Banana Skins, by Kristina Buch, is a two-channel video installation in a garage. Moved by bombed-out churches seen during her travels in Anatolia, the artist has taken inspiration from the last scene in Antonioni’s film The Passenger, blowing up nature and culture by pairing the Guggenheim Museum in New York and Mount Everest.

Another beautifully realized work with sad content is Silence of Ani, a black-and-white film by Francis Alÿs, set in the ruins of a medieval town on the banks of the Akhurian River, which separates eastern Turkey from Armenia. Children make bird calls by blowing on a variety of whistles as they play in the rubble. Their collective call yearns for the return of the birds. The film is shown at Depo, a cultural center in a building with floral casts on its facade, dating from the 1920s.

Füsun Onur’s installation, Sea, is an old fishing boat journeying up and down the Bosporus– a 31-km strait between Europe and Asia which connects the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara. The small white boat with sound sings of Ulysses and can be seen at various venues.

Istanbul’s magical charge, due to its history and location, has set free the artistic imagination of the participants in this year’s Istanbul Biennial. The variety of responses to the given theme captures the mood of the time, while highlighting the city’s architectural wealth in unique ways. Considering the time, effort, and organization that must have gone into an event of this magnitude in this sprawling city, I say “bravo” to Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, the artists, the organizers, and the volunteers involved in making it happen!

The Biennial, which opened on September 5, continues until November 1, 2015.