Orchestra dell' Accademia Nationale at Carnegie

Barbara Hannigan Sings Sciarrino

By: Susan Hall - Oct 22, 2017

Sir Antonio Pappano has made his mark at Royal Covent Garden over the past decade and a half. He is also the music director of the Orchestra dell' Accademia Nationale di Santa Cecilia (Rome). They return to Carnegie Hall after an almost half century absence. Pappano presented a work composer Salvatore Sciarrino wrote especially for the great and adventuresome soprano (and conductor) Barbara Hannigan. Mahler's Sixth Symphony followed.

Sciarrino has written: “ Music is emotional; it touches you intimately. Not everyone enjoys intimate contact. We live in a time of great diffidence, frigidity, and lack of joie de vivre, so music can become embarrassing. It embarrasses because it touches you, and being touched is erotic. It is music’s most beautiful trait.”

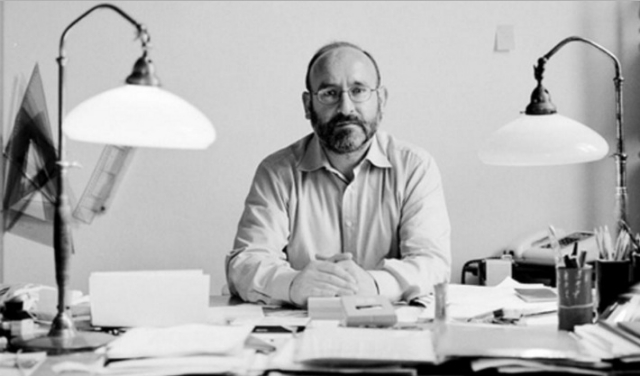

Pappano spoke to the audience before La Nuovo Euridice secondo Rilke was performed, discussing the composer's place in the current musical pantheon. Perhaps because Sciarrino is not a self-promoter, his work is less well known in England and the US than it is on the European continent. There he is one of the most frequently performed contemporary composers.

In taking on the Rilke version of the classic Orfeo myth, we hear the confusion of Orfeo and the failure of his music to penetrate the underworld of the dead, including his beloved Euridice. The life of any fable travels and settles, takes root and effervesces. At its heart is the struggle for a truth. It is hydra-headed here, Euridice, Orfeo and God impacted and never connecting. Could it all have been otherwise? No. Music is the unifier.

As Hannigan swirled onto the stage in a gown draped like an upside down group of calla lillies, her sure-footedness belied the emotionally wrought singing that was about to begin. Flowers is a theme in the Rilke poem. Patiens not impatiens are soft and full in the meadows. Rilke's sex is closed like a young flower at sunset. Hannigan is ready to root.

Familiar in this country as the lead soprano in George Benjamin's Written on the Skin, Hannigan is the go to performer for contemporary composers. Her selection of a work on which to collaborate is a form of endorsement. Her apt choice of Sciarrino was demonstrated note by deliberately stumbling note.

To tie music to the human experience and its expression, Sciarrino composes to match mood. This brings us to awkward and uncomfortable places. Curiously, Hannigan's lovely and pure basic tones unify stammerings and gutterals. Sometimes she will sit on a note endlessly, and give great auditory pleasure.

New sonic palettes are presented. They often have a warmth in the breath, even as they murmur and pulse. The interspersed quiverings and stammers are held together by both the singer and the orchestra.

In Hannigan's voice, you hear sound as a living creature. Vital signs abound. Sometimes the breathing is audible, indicating a body pulse. She is a miracle worker as she turns hushed tones into a bold declaration.

Pappano tied the Gustav Mahler Sixth Symphony to the first piece, explaining that both address man's feeling of horror and confusion.

It is true that the Mahler, conventionally composed in four movements including the sonata form and a gorgeous adagio, expressed angst. In this performance, the stammerings and stutters drawn by incomplete phrases that are endlessly repeated in various instrumental groups, were smoothed over as though they were being sung. This created an unlikely sense of unity. It is difficult to appreciate the symphony when it is not abrupt, yearning and fearful.

The orchestra performed superbly under Pappano, to whom they gave a full bow tapping appreciation at the end of the concert. The audience at Carnegie Hall was also thrilled by the evening's fare.