The Opera Orchestra of New York Returns to Carnegie Hall

Debutant(e)s Abdrazakov, Alagna, Garanca and Guleghina

By: Susan Hall - Oct 27, 2010

Cavalleria Rusticana

by Pietro Mascagni

The Opera Orchestra of New York

Conducted by Alberto Veronesi

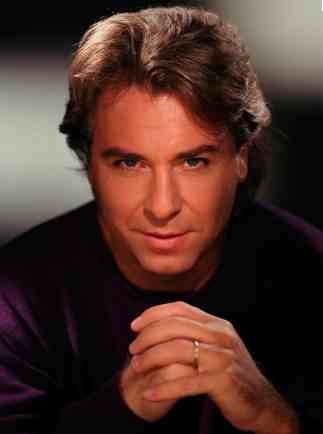

Turiddu, Roberto Alagna

Santuzza, Maria Guleghina

Mamma Lucia, Mignon Dunn

Alfio, Carlos Almaguer

Lola, Krysty Swann

La Navarraise

by Jules Massenet

General, Ildar Abdrazakov

Anita, Elina Garanca

Ramon, Isaachah Savage

Remigio, Brian Kontes

Bustamente, Michael Anthony McGee

The New York Choral Society

John Daly Goodwin, Music Director

Carnegie Hall

October 25, 2010

The Opera Orchestra of New York brought together the New York Choral Society and several great principal singers to perform the often heard, but always fresh, Cavalleria Rusticana and the beautiful but seldom heard La Navarraise. Like Carmen, both are operas propelled by jealousy. Navarraise, a French take on Cavalleria, has been called Cavalleria Espanola.

Roberto Alagna/Turiddu sings offstage to his love Lola, who married another man while he was away at war. We learn that he has seduced a village girl, Maria Guleghina/Santuzza, to avenge Lola’s betrayal.

Guleghina, looking like a princess in her full length, layered black silk dress, was in splendid form, of particularly lush middle range. She is crushed when Turiddu/Alagna returns to Lola. She gets her revenge by provoking Lola’s husband. Guleghina brings a moving emotional take on the role, about which an early critic wrote, "a furious exhaltation of song." That it was.

Jealousy on jealousy on jealousy is always swirling around Alagna, yes, because he sings so beautifully, but also, because he is such a bad boy. He could not resist cupping his hand on Lola’s derriere.

Lola was sung with seductive loveliness, by mezzo Krysty Swann, in a form-fitting bright red dress. This young performer has, understandably, received many prestigious awards.

Mignon Dunn, continuing her long operatic career, sang Turiddou’s mother, who runs a wine shop in town. It is the center of activity in the foreground, while an Easter mass is performed in church.

Although this was a concert production, you got the distinct feeling of verismo – a real town in real time, with townspeople reacting to the drama of the principals. There are no moments when time freezes and a character stops to sing his emotions. Instead, characters like Alfio take no more time than real life people would to express feelings. Carlos Amalguer sings his to particular effect. Turiddu says “Compare Alfio,” stops, and then a cello continues his thoughts.

After the sudden fame that came to Mascagni, the composer took on the mantle of savior of the operatic form. In one stroke, he buried “the anemia in opera” and "brought distinctive musical ideas, shaped clearly…no textbook exercises here.” His wife however remained “the same frugal, domestic woman, washing her Pietro’s socks and handkerchiefs with her own hands, brushing his suits, and polishing his shoes.” Mascagni must have understood Santuzza well.

Gemma Bellincione, about opening night, wrote: “You cannot even have the barest idea of what happened in the hall...At the end of the opera the spectators appeared to go crazy. They screamed…” So it has been ever since as it was at Carnegie.

La Navaraisse was a welcome second half of the program. Early on, pairing Navarraise with Cavalleria was common, but we are more accustomed to Pagliacci. The one act opera by Massenet was a perfect companion piece, set in Spain, and bringing the Latvian soprano, Elina Garanca, straight from her triumphant Carmen at the Met. Her voice has not yet developed the husky, dark quality Carmen demands, but is perfect in the light and melodic Navarraise.

Garanca and Alagna are at it again. His father has insisted that Alagna/Araquil can only marry the woman he loves, Garanca/Anita, who is dirt poor, if she comes with a large dowry. She makes a deal with the General, sung by Ildar Abdrazakov, in his rich and deeply colored bass, agreeing to pay her a vast sum if she can kill the general leading the troops that oppose him. She does, but Araquil, dying from a battle wound, imagines that she has earned this money on her back. He dies cursing her, and she goes mad. Since Garanca is such a consummate actress, the evening's only regret was that she didn’t have a chance to display madness at the opera’s conclusion.

George Bernard Shaw wrote about this simple and powerful drama, “The assumptions, explanations and pretexts on which they are brought about are so simple and convenient that nobody minds their being impossible.”

The orchestra was admirably conducted by Alberto Veronesi, who comes to New York from a brilliant Italian career. He brought verve and attention to nuance, even in what is called the noisiest of all operas, Cavalleria. The New York Choral Society, directed by John Daly Goodwin, provided the liturgical background to Cavalleria, and a smaller group from the Choral performed in Navarraise.

The Opera Orchestra cancelled last season. Its return in these performances of vitality and style suggests a promising future. Their largest contributor is none other than Dr. Agnes Varis. She brings rush tickets daily and in a weekend roulette to Metropolitan Opera fans. She made the donation to the Opera Orchestra in honor of her late husband Karl Leichtman.

Dr. Varis is surely the biggest star of the New York opera world. She creates reasonable access to good seats at the Met, and the survival of an organization like the Opera Orchestra.