Building the Revolution

Soviet Architecture and Art 1915-1935 At Royal Academy

By: Mark Favermann - Oct 30, 2011

BUILDING THE REVOLUTION: SOVIET ART AND ARCHITECTURE 1915–1935

29 October 2011 – 22 January 2012

The Royal Academy of Arts in London just opened an exhibition Building the Revolution: Soviet Art and Architecture 1915–1935. The show focuses on Russian avant-garde architecture made during a short, intense period of design and construction from 1922 to 1935.

Inspired by Constructivist art, Russian and Eastern European architects transformed this radical visual language into three dimensions, conceptualizing and creating structures that incorporated an innovative style that portrayed the energy and optimism of the emerging Soviet Socialist state.

Constructivism was an artistic and architectural philosophy that originated in Russia and emerged after World War I. It was a rejection of the idea of art for art's sake in favour of art as a practice for social purposes. Constructivism had a great influence on modern art and architecture movements of the 20th century.

Constructivist architecture emerged from the wider constructivist art movement. Its roots are in Russian Futurism. Constructivist art had attempted to apply a three-dimensional cubist vision to wholly non-objective abstract 'constructions' with a kinetic element.

After the Russian Revolution (1917), it turned its attentions to the social demands and industrial tasks required of the new regime. Two distinct threads emerged, the first was espoused by Antoine Pevsner and Naum Gabo in their Realist Manifesto: a concern for space and rhythm; the second was argued between two philosophies-one that stressed pure art and and the other that stressed only social utilitarian function.

Led by Alexander Rodchenko and Varvara Stepanova and Vladamir Tatlin, constructivism became a form that was a part of industrial production. By 1922, when Pevsner and Gabo emigrated, the movement developed along socially utitlitarian lines and became the dominant influence on soviet architecture until the early 1930s.

It influenced major schools of thought and aesthetic trends such as the Bauhaus and the De Sjil movements which in turn influenced what became the Modern Movement or as it was called in the US, the International Style. Constructivism's influence was somewhat pervasive, with major impacts upon architecture, graphic and industrial design, theatre, film, dance and even fashion.

There is a heroic hubris to Constructivism. The various artists affiliated with the movement felt that the very nature of their art allowed for an optimistic human outcome. This seems quite naive and Quixotic today. In a way, this is a wonderful utopian premise, even if its potential was never really achieved.

To interpret this creative period, the Royal Academy's exhibition involves large-scale photographs of extant buildings with relevant Constructivist drawings and paintings, vintage photographs and periodicals. Many of the works have never previously been shown outside of Russia and Eastern Europe.

The utopian zeitgeist of a new Socialist society in Russia encouraged a fusion of radical art and architecture. In this hand-drawn era, many architects were artists as well. This creative firmament was reflected in the engagement with architectural ideas and projects by such artists as Kazimir Malevich, Vladimir Tatlin, Liubov Popova, El Lizzitsky, Ivan Kluin and Gustav Klucis.

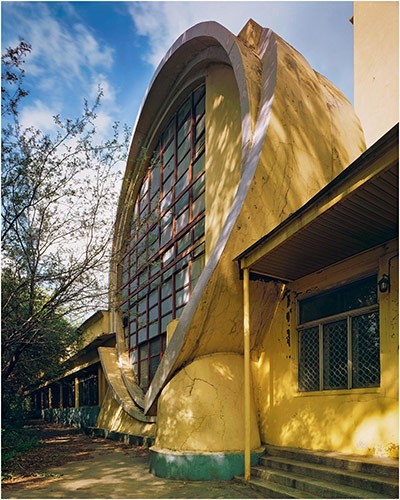

This radical creative philosophy was interpreted into structural designs by such architects as Konstantin Melnikov, Moisei Ginsburg, Ilia Golosov and the Vesnin brothers, as well as non-Russians like Le Corbusier and Erich Mendelsohn. These European architects were enlisted by the new Soviet state to assist in shaping their concept of a new utopia.

Their novel buildings were often streamlined, flat-roofed, white-walled, utilizing industrial materials and with experimental fenestration. They appeared to be quite alien among the surrounding traditional low wooden structures in densely compacted nineteenth century commercial and residential blocks. They were to be structural beacons of a new era.

Most prominent in what was then the USSR cities of Moscow and St. Petersburg, they also impacted other urban cities such as Kiev, Ekaterinburg, Baku, Sochi and Nishni Novogorod.

As part of a campaign to preserve these iconic buildings, many of which have either fallen into disrepair, undergone inappropriate transformations, or been threatened with demolition, the architectural photographer Richard Pare has documented as many of them as possible in a series of sympathetic and timely images made over the past two decades.

The historical, political, social and cultural context in which these modernist structures were created is presented through vintage archival photographs from the Schusev State Museum of Architecture, Moscow (MUAR), often showing the buildings under construction or soon after their completion.

Many of these photographs have never been exhibited before either, in or outside Russia. They are complemented with paintings and works on paper from the George Costakis Collection of Constructivist Art, currently housed at the State Museum of Contemporary Art in Thessaloniki.

The inclusion of these pieces will demonstrate the vital experimentation of Russian avant-garde artists from 1915 to 1935, as well as the intense dialogue that developed between them and radical architects, contributing to a new, revolutionary language of architecture.

Although Russian modernist architecture has long been recognized as a distinctive and significant moment in the history of architecture, it has been rarely published in recent years and therefore remains little known. There is a sadness to this. The creative fires lasted a mere 20 years and were rather violently doused by the Soviet bureacracy.

Since the 1990s important material relating to the Contructivist movement has surfaced in Russia. It has become easier to access the buildings if they still exist. Together these factors have encouraged new research into and a greater understanding of this unique if doomed period.

The exhibit is arranged thematically, with sections focusing on residential buildings, factories, health facilities, communications and transport. Each section explores particular advancements and nuances within the different building types. The architecture is illustrated and brought to life with a mixture of contemporary and vintage photographs.

An intriguing find in the exhibit is the creative brilliance of the work of Konstatin Melnikov. His buildings, especially his workers' centers, embodied the notion of optimistic form and function in graceful and surprising ways. Apparently his briliance could not be embraced by the Soviet bureaucracy. The structural monstrosities that followed in the Soviet block countries underscored an demonstrably unheroic and even pesimistic aesthetic quality to the dictatorship of the proletariate.

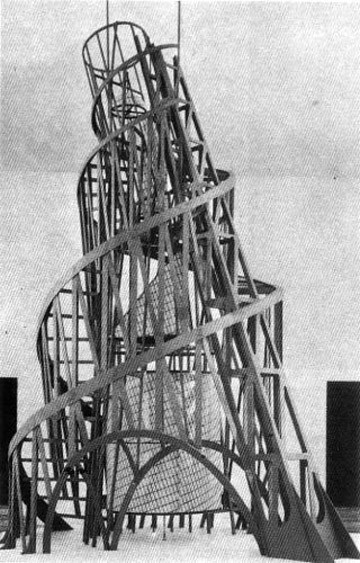

In conjunction with the exhibition, a reconstruction of a large model of the never actually built Vladimir Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International, also known as Tatlin’s Tower, is installed in the Royal Academy’s Annenberg Courtyard. This "heroic" unbuilt structure has been the visual symbol of the Constructivism movement.

A wonderful surprise of this exhibit is the great, no brilliant work of Konstatin Melnikov. His various workers centers demonstrate the potential greatness of what could have been if creative architects would have been allowed to flourish in the Soviet Union. Somehow, his work got done. His buildings were the wonderful exception versus the terribly inhuman Soviet architectural rule.

This exhibit share's a sad but sometimes beautiful short period of aesthetic optimism based in philosophical utopianism. Alas, there is never a utopia. The Soviet system demonstrated that. This is an exhibition that suggests human creative potential and speaks to the sadness of unfilled dreams.

Royal Academy of Arts, Burlington House, Piccadilly, London W1J OBD