Dream and Reality at Istanbul Modern

A Celebration of Woman Artists of Turkey

By: Zeren Earls - Oct 31, 2011

Dream and Reality paints a vibrant picture of modern and contemporary art in Turkey, while providing a chronological history of the country’s women artists since the early 1900s. Held concurrently with the 12th Istanbul Biennial, the exhibition introduces 74 women artists to a global audience through a variety of art forms, from painting and sculpture to video installations.

Located next door to the Biennial exhibitions, Istanbul Modern is a beautifully transformed former warehouse (Antrepo 4) on the shores of the Bosporus in the harbor district. In addition to its respectable permanent collection, the museum presents the latest trends in international contemporary art, as well as exhibitions and retrospectives of prominent Turkish artists. The Dream and Reality show offers a comprehensive anthology from the early years of the Republic to today, focusing on Turkey’s social and cultural transformation through the work of women artists.

Curated by Levent Çalιkoglu of Istanbul Modern, feminist academic and activist Fatmagül Berktay, and art historians Zeynep Ínankur and Burcu Pelvanoglu, the exhibition takes its title from the 1891 novel, Dream and Reality, coauthored by Fatma Aliye Topuz, the first female Turkish novelist, and Ahmet Mithat, a male journalist. The two-part romance features the period’s symbolic characteristics, with the dream part written by Fatma Aliye and the reality part by Ahmet Mithat. Fatma Aliye is featured on the cover of the novel with the pen name “A Woman,” whereas the author of the part on reality is credited by his given name.

The exhibition takes a unique look at the changing identities of women in the arts, culture, and society, revealing the artists’ intellectual bearing and practices. The chronological format reflects the age and society the artists live in, conveying their experiences in the social arena and pointing to layers of reality both visible and invisible. Themes concerning women’s lives — patriarchy, gender roles, family, migration, sexuality, and violence — are central to the works.

Early works by graduates of the School of Fine Arts for Girls, founded in 1914 during Ottoman westernization, consist of portraits and figurative paintings, which released women from a life of domesticity, leading to depictions of modern women of the Republican era after 1923. Hale Asaf’s Self-Portrait exemplifies the differences in the way women were represented in Ottoman and Republican times. It downplays the femininity of women in the former period and emphasizes their elegance and refinement in the latter one, offering a Western and contemporary image.

Fahrelnissa Zeid (1901-1991) expresses her emotional world through color abstraction. In Abstract (Temporality, Water, Sun) 1953, colors and movement relate to chaos and dynamism on the earth, in space, and in humankind. Zeid’s sister, Aliye Berger (1903-1974), breaks away from conventions with her abstract and free-form oil painting, Sun Rising, 1954, marking a turning point in both the political life and the artistic tendencies of the period.

Maide Arel (1907-1997) shows the influence of Anatolian culture in Embroidering Girl, a portrait-style figurative painting with folkloric subject matter. Eren Eyüboglu (1907-1988) also has a folkloric language of her own. Portrait of a Woman in Blue Dress emphasizes the distinguishing traits and spiritual characteristics of the model, combining the artist’s approach to color with cubist stylistic influence.

Semiha Berksoy (1910-2004), Turkey’s first opera singer, intertwines “herself” with the roles she played in operas, expressing momentary feelings, such as in Ariadne auf Naxos and Salome. Frumet Tektas (1912-1961) and Leyla Gamsιz (1921-2010) both reflect the influence of their studies in Paris at different times — late cubism and Art Deco in the case of Tektas’s Portrait, and a sound ordering of colors in the technical composition of Gamsιz’s Untitled 1956, where a figure is surrounded by thick black paint and emphasized by contours.

Naile Akιncι (1923) examines, in Eyüp 1954, the Istanbul neighborhood of the same name, noting its plant cover, architectural fabric, and atmosphere. The artist’s signature Eyüp series deals with geographical, cultural, and sociological developments over a period of 50 years.

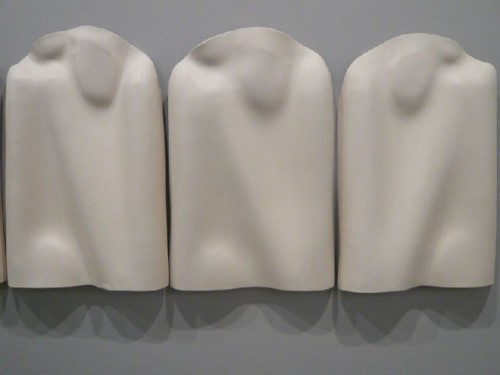

Candeger Furtun (1936) creates a 10-piece ceramic wall installation, The Silent Ones, exploring the past through her memory and experience of the society in which she lives. Anonymous female bodies, created individually with one hand on the opposite shoulder, exist silently, observing their surroundings, but not entering into any discourse.

Füsun Onur (1938) reconsiders the definition of sculpture by using found objects in Untitled (Chair, chain and name tag). The work shows a chain stretched over the chair, where the artist’s name tag sits, implying an attitude of the outside world toward her. “Chaining” the place set aside for the artist may be read as an expression that she has not found the recognition she deserves.

Nur Koçak (1941) is one of the pioneers of photorealism in Turkey. The series Cahide’s Story, made between 1996 and 2003, takes as a starting point the life of Turkey’s first female director, Cahide Sonku, who produced important works in cinema and theater in the 1930s. The portraits are divided into two groups — “before” and “after.” In the “before” group Cahide is a smiling, confident beauty, whereas in the “after” group she is an anxious, fatigued woman, who becomes a prototype for Koçak’s message — an image of woman as an object of consumption in the visual culture, altered and reduced as time passes.

Canan Beykal (1948) pays homage to Mihri Müsfik, one of Turkey’s first female painters, in Mihri’s Column. A revolving porcelain doll sits on a black column in front of a self-portrait of Müsfik, done as a critique of the position of women in 20th-century Ottoman society. As the doll revolves, she invites a metaphorical examination of women of this period from every direction.

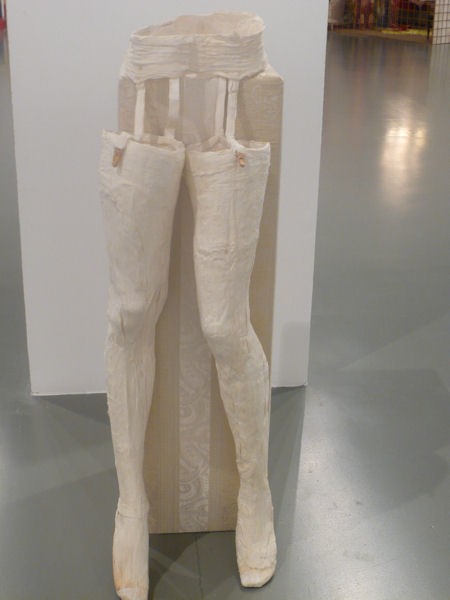

Azade Köker (1949), both in Bridal dress and in Someone not here, a mixed media sculpture of a pair of legs with garter belt, deals with issues of women who are squeezed between tradition and modernity and who are forced to accept urban life as it is offered, growing ever more withdrawn.

Cage Projects 2: Kitsch Room by Kezban Arca Batιbeki (1956) puts women in a beaded Cage, mirroring Turkish society and dominated by tabloids and TV screens. Exploring the theme of Istanbul continually undergoing change because of migration, the installation is a chamber of selected and collected images, ranging from toys to kitschy objects and photographs taken from black and white Turkish films — a male world which women must navigate.

Another work about immigration is Bring yourself to me by Handan Börüteçene, who places African masks and suitcases of Turkish migrants to France on old chairs belonging to the National Museum of the History of Migration in Paris. To complete the piece, viewers are asked to discover the marks on the suitcases with the aid of magnifiers and to recall their own memories. The installation of 19 suitcases, 19 chairs, and 30 magnifiers on wheels has an arresting presence in the lower lobby of the museum.

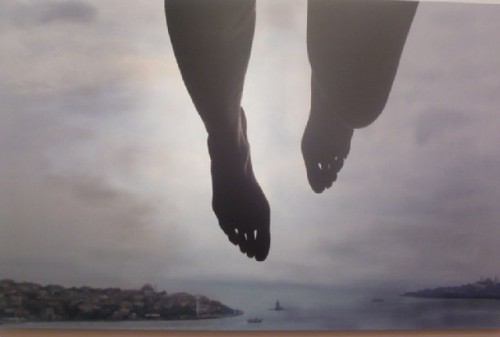

In Falling, Gül Ilgaz (1962) displays her power to stand in the middle of the cultural and political divide believed to exist between East and West, represented by the Bosporus. In the photograph we see a courageous body plunging into the dark waters of the strait, reflecting the relationship ridden with contradictions that the body establishes with Istanbul. The image conveys the ups and downs of life itself and of Istanbul, the need for alleviation under the weight of the loads we bear, and an effort to find one’s balance.

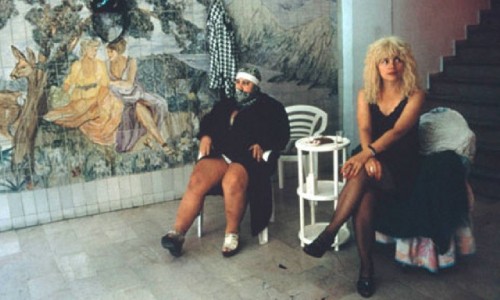

In her video Bordello, Sükran Moral (1962) transforms a brothel on Yüksek Kaldιrιm in Istanbul into a platform for performance. In the role of a blonde hooker in stilettos, the artist walks up the broken steps of the notorious district and places herself at the door of one brothel holding a “For Sale” sign, then another sign for an Art Museum. Men gather round; one begins to sing to her, and another one dances for her, banging on an ashtray like a tambourine, while restless others lurk in the crowd. Using her body and identity, Moral aims to deal with entrenched social concepts of power and sexuality with humor.

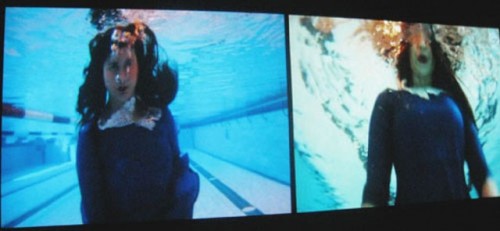

Nezaket Ekici (1970) also uses her body as a means of expression. Her video Discipulus 2011 shows her in school uniform, submerged in water, struggling for air — a comment both on the issue of discipline and the difficulty younger artists encounter in surviving and being heard.

Aslι Sungu (1975) deals ironically and humorously with the rituals of daily life, questioning how right and wrong are defined by power. In her two-channel video, Just like Mother and Just like Father, she gets her parents to dress her.

Nilbar Güres (1977) explores areas of freedom and resistance created by women in a male-dominated society when they migrate to the city and are squeezed in by different lifestyles. She shows us women who ignore and deny pressure, in order to live as they please. In her video Undressing, the artist is wrapped like a mummy in swirls of cloth. She peels layer after layer of scarves from her head, feeling for the clasp and the edging of each to name whose it is. While waiting for her face to be revealed by the flesh-colored cloth, we feel the intense inner lives of family members as each headscarf is appropriated.

Overall, the exhibition is an impressive historical overview of Turkish woman artists, who provide us with a subtext of what it is to be a woman in Turkey. Engaging the viewer with wit, humor, and accomplished esthetics, the artists establish their pioneering and critical position in a rapidly changing country.