Stephen Hannock Paints a Masterpiece for Sting

Taking Art Not Coal to Newcastle

By: Charles Giuliano - Nov 02, 2008

After four years of research, development, design and execution, Friday, October 17 was finally "varnishing day." It was also the last chance to view the 8 x 12' painting "Northern City Renaissance: Newcastle, England (Mass MoCA #79-E)" by Stephen Hannock. It was laid out flat in the artist's North Adams studio. So Astrid and I returned on Saturday to catch another look. It was being professionally photographed as the final image for a new book.

On Sunday, as Stephen explained, the stretcher would be folded in two and the painting would be placed in a crate and then into a second crate. By now it has cleared Customs and is on its way to Newcastle upon Tyne where it will debut soon and remain on view for an extended period of time.The painting will be on view at the Laing Art Gallery in Newcastle from November 1 through February, 2009. Link to Sting's site on Hannock project

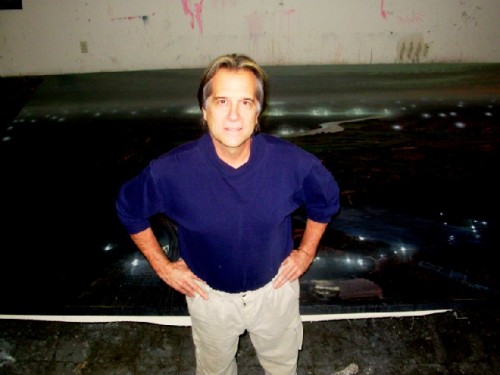

The enormous painting, a bird's eye view of the industrial city in Northern England, was a commission from the musician Sting (Gordon Matthew Thomas Sumner) who was born in Tyneside on October 2, 1951. Hannock and Sting became friends some 25 years ago when he first started to acquire the artist's paintings starting with one of his phosphorescent early works. "Sting and Trudy have the most diverse collection of my work." Hannock said.

Once the painting is shown in Newcastle it is unclear what will occur after that. Originally, there were plans to show it briefly at Mass MoCA before it left for England. But there was not enough time before the deadline for that to happen. It may yet be shown at the Tate. Discussion has involved it being given to a major museum or Sting may keep it. Whatever happens Hannock hopes that it will be widely seen and included in any future, museum level retrospective. There are museums looking for major works by the artist. While the studio is productive, clearly, with four years of development, work on this level is scarce and coveted.

After such an intensive process we asked how he felt? Was there a sense of letdown and post project blues? Perhaps it is too early to say but it will not be any time soon that we see such a large canvas in the studio. There are a couple of others on this scale including a view of the "Oxbow" in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Met also owns the version of the "Oxbow" by the 19th century Hudson River painter, Thomas Cole. Hannock was inspired to paint the Oxbow because of a long time residence in Northampton when he was an apprentice/ student for Leonard Baskin. Stephen explained that because of the technical process of how he works this is about the limit of a stretched canvas. For such a large work there has to be an inspiring subject.

It is not a stretch to say that the view of Newcastle is on the short list of his most important and original works. Arguably, it is his masterpiece. It has set the bar high for the future but, at midcareer, Hannock has lots of fire in his belly. It is ironic that this important painting will be, at least for now, remote from the mainstream of the art world and its critics. Unless, in the next few months, there are pilgrimages to Newcastle. Which may be what Sting had in mind in promoting the cultural Renaissance of a city which was known primarily as a tough town for mining and ship building. Now that industry has long ago shut down, just like North Adams here in the Northern Berkshires, Newcastle is being reborn as a center for art and culture. In the center of Hannock's painting, at the edge of the Tyne River which runs through the city, is a rendering of the Sage Gateshead, a dramatic cultural center designed by Lord Norman Foster.

Just about a year ago I visited Hannock's studio on assignment for Art New England. He was finishing a version of the Oxbow in time for the dedication of the expansion of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art. In the studio at the time was a large landscape commissioned for Sundance Institute in Utah. In addition to a short magazine piece I wrote a longer version for Berkshire Fine Arts. This initiated a discussion to document the progress of work on the Newcastle project. Prior BFA article on Hannock

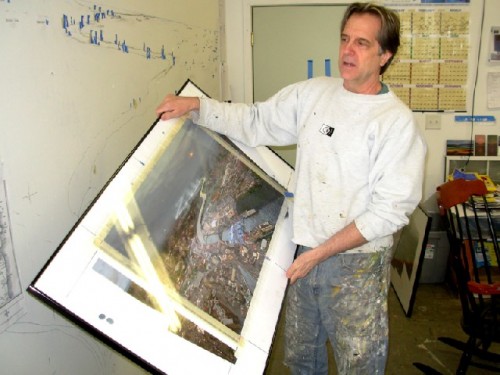

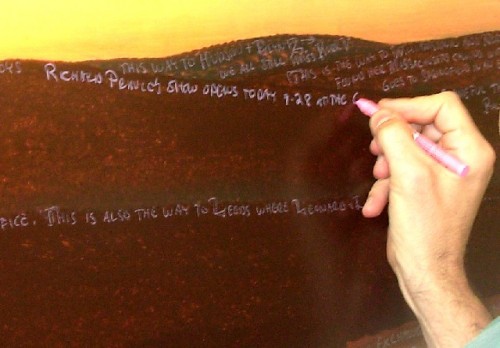

There were studio meetings at intervals lasting on average one to three hours. These were recorded by the video artist, David Lachman, Stephen's assistant. The exchanges were far reaching about the process and sources for the work. It helped to understand how Hannock does not just create an image of a scene. More than a landscape, in the traditional sense, he develops portraits of what is depicted. The paintings are layered with collages of related images fixed to the surface. These are then painted over and sanded down, with a building up of layers of pigment. He also writes stories and thoughts onto the surface. From a distance little of this is visible as the details converge into a total view of the subject. Describing the text he commented that it is applied "free hand like a brush stroke."

As we approach his paintings we observe, discover, and become involved with the rich and dense layering. But there is no commitment to preserving the integrity of any single element. It must merge and come together as a painting. The whole prevails over the sum of the parts.

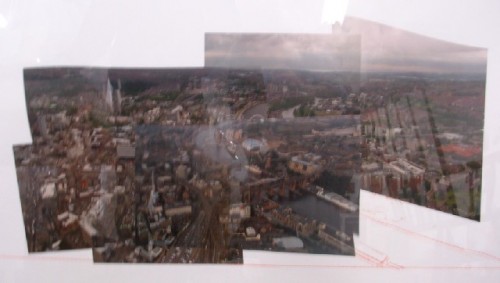

It was a long and intense process to get there; to reach "Varnishing Day" when the work finally gets pushed out the door and into the world. This project started four years ago when Hannock hired a helicopter to fly over the city where he was able to create a series of photographs. With a bit of humor Stephen pointed to a sign for the helicopter service which remains quite visible. "He gave me a break on the price so I wanted to give him a plug" Hannock said. It is typical of his generosity. He also showed me a number of "Prizes" and "Awards" created for charities. Currently there is a study for "Newcastle" included in an auction to benefit Mass MoCA. Another study from the series is in the collection of the Berkshire Museum in Pittsfield which organized an exhibition of the work in progress.

A number of the views of Newcastle were assembled into a collage. This was scanned and printed digitally. Hannock then painted over that. It was rescanned and reprinted which Hannock again over painted. The process was repeated as the artist moved ever closer to what he wanted to put onto the large canvas.

In the process of research he identified the many mines and their locations. The painting represents them allegorically as points of light reaching into the sky. Along the Tyne are larger pools of glowing light representing the major shipyards next to the river. He also discovered that there had been many works created in the 19th century by artists who went down into the mines some of which extended for miles under the ocean. Among the artists of that time was the Newcastle born master, John Martin. Hannock discovered a relative the Pre-Raphaelite artist Alfred William Hunt. Whose most renowned work was a view of the Tynemouth Pier. Hunt was his great, great, great uncle. He pointed out that detail with evident pride in his heritage.

To develop the historic/ narrative aspects of the works the artist conducts his own research. He does not want to be overwhelmed by detail and the use of text is not intended to provide a history of the subject. There is of course a lot to show and tell about Newcastle. The city still entails elements of Hadrian's Wall built by the Romans to hold back migrations from the North. In later times New Castle (named for its fortifications) held back the Scots until they were subdued. The Stone of Scone of Scotland became symbolically included into the Coronation Chair in Westminster Abbey. It signifies that the monarch rules over the United Kingdom. The Stone was a prize of war caputered by Edward I in 1296.

Over the course of the studio sessions it was fascinating to speculate how all of these elements would come together. For the most part it seemed that progress was incremental and we wondered how the artist would be able to meet the deadline. In the meantime there were other works and projects going on as well as the artist's personal and social life. There are many demands on his time and attention.

Summer was intensely busy as high season for the arts in the Berkshires. Now and then I would connect with Dave Lachman at an opening and get periodic updates. When I returned to the studio, some months ago, the painting was blocked out as a full scale cartoon on a studio wall. This occurred while the stretcher and canvas were being prepared.

Recently, Dave gave me a head's up that it was almost finished. When I called Stephen's response was "Where have you been stranger?" We agreed that I would call at 11. But he suggested coming later in the afternoon as the varnish needed to dry.

Having followed the progress for the work over the past year I knew what to expect. But the scale, beauty, and mystery of the finished painting was overwhelming. I was astonished at how painterly it proved to be. At a smaller scale in the studies I had wondered how he would handle all the detail and rendering. From a distance it is all there.

At close range the buildings are painted with a loose and fluid brush stroke. Here and there under the final glaze you can see drips of the acrylic paint. Surely the artist could correct these "mistakes" but they are a part of the process. I commented that I had expected something more like a Richard Estes. That evoked a good natured laugh indicating that representation and realism was not what the work is about. In the lower right hand corner, over a dark area, were specks of dust. Like a fly in amber now embedded into the work. Again, with a shrug Hannock responded that, hey, it's a part of the work resulting from sanding down the surface which creates dust. You had to wonder, in some future "restoration" whether this "flaw" will be removed when the painting is revarnished. Like the scrubbing off of subtle glazes from a sublime Titian, or destroying the a secco overpainting by Michelangelo under the grime removed during the "cleaning" of the Sistine Chapel Ceiling.

Over time strange things happen to works of art. Turner's "Rockets and Blue Lights" in the Clark Art Institute which was "cleaned" a couple of years ago just doesn't feel right despite the careful study and science that went into it. The "cleaned" condition of Sargent's "Daughters of Edward D. Boit" in the MFA is not the painting I grew up with. Now that the girls are out of the shadow they are entirely different for a viewer. They have lost their former mystery and romance.

It surprised me that Hannock's "Newcastle" is somber and dark. The time of day appears to be near dawn. The subdued light level fuses the elements and makes more evocative those beacons of light signifying the spirit of the generations, if not centuries, of those who scratched a living from the bowels of the earth. To the left and right in the corners of the painting are symbolic figures of miners derived from those historic paintings. I asked Stephen about the cloud that envelops the top of the painting. "That's a fog bank rolling in" he replied. It is a familiar phenomenon in Newcastle and perhaps the ultimate metaphor for how a city and its history have been shrouded by time and tradition. It reminds me of Corregio's sensual "Jupiter and Io."

I regret not having more time to absorb the finished work. Like the "Garden of Earthly Delights" by Bosch in the Prado one could spend hours and days in front of this brand new masterpiece. Thanks Sting for having the passion and vision to make this possible.