Marsden Hartley: The German Paintings 1913 to 1915

LA County Museum of Art to November 30

By: Charles Giuliano - Nov 05, 2014

Marsden Hartley: The German Paintings 1913 to 1915

LA County Museum of Art

Organized with Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin

Curated by Dieter Scholz

LA August 3, 2014–November 30, 2014

With just 28 works roughly of the same scale installed in three galleries Marsden Hartley: The German Paintings 1913 to 1915, on view at the LA County Museum of Art through November 30, manages to capture lightning in a bottle.

In a tiny window of just three years Hartley (January 4, 1877 – September 2, 1943) embraced Cubism and European modernism in a brilliant manner that identifies him as America’s most advanced artist of his generation. This remarkable body of work ranks him shoulder to shoulder with the greatest European artists of that remarkable era.

Prior to sailing for Europe in 1912, with the not surprising destination of Paris, he had shown with Alfred Stieglitz, who with Lillie Bliss, sponsored his travel.

In the City of Lights he was soon adopted into the circle of Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas. Through their weekly salon he met leading artists including Picasso and Braque among others. He adopted their experiments in synthetic cubism filtered through an American tradition of narrative.

The brilliance of Hartley’s work was the manner in which he conflated the flattened space and collage like compositions of cubism with his own story telling obsessions.

Indeed, what a tale he had to convey.

A gay man attracted to virile men he was entranced upon meeting two German officers Arnold Rönnebeck, who was also a sculptor, and Karl von Freyburg, Rönnebeck’s tall, blond cousin. He soon joined them in Berlin.

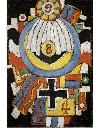

His lover, Karl von Freyburg, was an early casualty of the ensuing war. Hartley expressed his grief in the seminal German Military Series with assemblages of abstracted uniforms and references to his lover in the initials K. v. F. and the numerals 24, his age when killed, as well as other indicators of his regiment.

These works range from literal mounted cavalry on parade to boldly designed, starkly contrasted, abstracted patterns with a mordant bond of prevailing black ground.

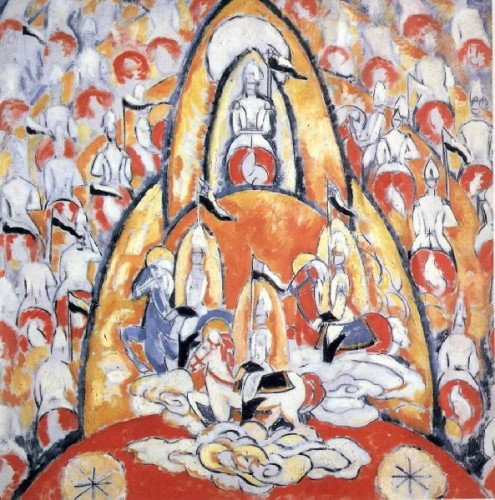

While obsessed with expressing grief the artist pursued other interests. He explored Eastern philosophy and religions. There is a strong current of symbolism in the work in a manner more evident than Kandinsky’s explorations in Über das Geistige in der Kunst. The leading Russian artist was an influence on his work after they met in Munich.

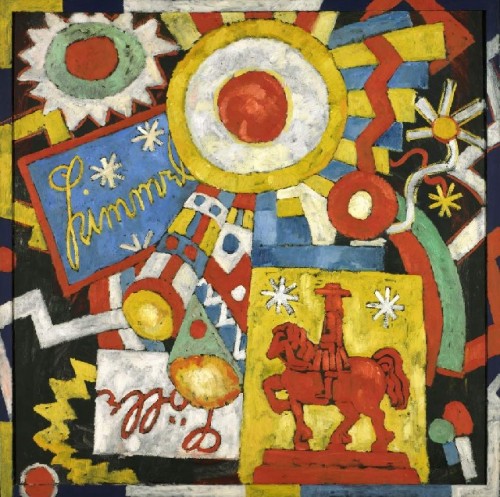

In another body of work on display in LA it is tantalizing that Hartley was a progenitor of Pop Art. In his Amerikan Series he created confounding pastiches of Indian themed kitsch. It is speculated that the painting were created to appeal to German collectors.

Several years ago the art historian, Wanda Corn, then a Clark Fellow, delivered an intriguing lecture on these works. She discussed the popularity of dime novels of Karl Friedrich May (25 February 1842 – 30 March 1912). They celebrated frontier tales of the American West. That interest in cowboys and Indians continues today with Germans attending powwows in buckskin and feathers.

This stunning exhibition was the icing on the cake of an interest in Hartley starting as an undergraduate encountering Hartley’s “Musical Theme Oriental Symphony” (1913) in the collection of the Rose Art Museum of Brandeis University. It would take decades for the thinly painted, symbolist/ cubist work to reveal its mysteries.

While less celebrated than its depth in Pop the Hartley work is among the greatest holdings of the Rose. When not installing shows, under former director Carl Belz, the artist/ preparator Roger Kizik created unique frames for special works. His carving for the Hartley wonderfully echoed the patterns in the painting. His treatment so richly enhanced the experience and understanding of the work.

It was so sad in LA to encounter the painting stripped of that loving tribute. Now it looks stark and plain in a generic frame.

The conventional story is that upon returning to America in 1915 Stieglitz emphatically refused to show or sell the German Military Paintings. The artist was told to paint America. It is also usual to say that the artist never again reached the thin air he breathed in Berlin. That is and isn’t true. He continued to create remarkable works that more comfortably fit into the canon of A list American modernism.

In the essay for the 1980 Hartley exhibition at the Whitney Museum Barbara Haskell related the poignant saga of his personal and professional travails. A shocking passage relates how, when he couldn’t afford the storage fees for his work, the artist was compelled to destroy paintings to fit into a smaller space. It is remarkable that the German paintings survived and agonizing to consider what was likely lost.

Upon returning to America Hartley was in perpetual motion; Cleveland, New York, Boston, Gloucester, New Mexico, California, Mexico, Bermuda, Maine and Nova Scotia.

As one might say looking for love in all the wrong places.