Learning to Take the Triangle Seriously: Liszt at Bard III

The Final Liszt Weekend at Bard College Sums Up a Monumental Career

By: Michael Miller - Nov 07, 2006

Fall Program Two: The War of the Romantics: Weimar and Leipzig

Saturday October 28, 2006

2:30 pm Preconcert Talk: Dana Gooley

3:00 pm Performance: Faculty and students of The Bard College Conservatory of Music: Melvin Chen, piano; Ida Kavafian, violin; Robert Martin, cello; Steven Tenenbom, viola; Peter Wiley, cello; Allegra Chapman, piano; Luosha Fang, violin; Leah Gastler, viola; Liyan Liu, viola; Shuanshuang Liu, viola; Renata Rakova, clarinet; Xin Tong, piano; Tina Zhang, violin

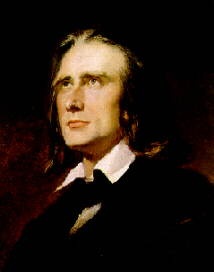

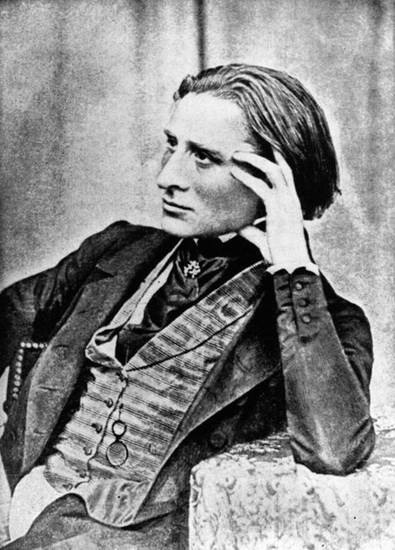

Franz Liszt (1811–86)

Felix Mendelssohn (1809–47), Piano Quartet No. 2 in F Minor, Op. 2

Schlaflos, Frage und Antwort

R.W.—Venezia

Après une Lecture de Dante, from Les Années de pèlerinage

Robert Schumann (1810–56), Märchenerzählungen, for clarinet, viola, and piano, Op. 132

Johannes Brahms (1833–97), String Quintet No. 2 in G Major, Op. 111

Fall Program One: The New German School and Musical Narrative

Saturday October 28, 2006

Fisher Center, Sosnoff Theater

7:00 pm Preconcert Talk: Christopher H. Gibbs

8:00 pm Performance: Simone Dinnerstein, piano; Nardo Poy, viola; American Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Leon Botstein, music director

Franz Liszt (1811–86)

Les Préludes, after Lamartine

Piano Concerto No. 1 in E-flat Major

Totentanz

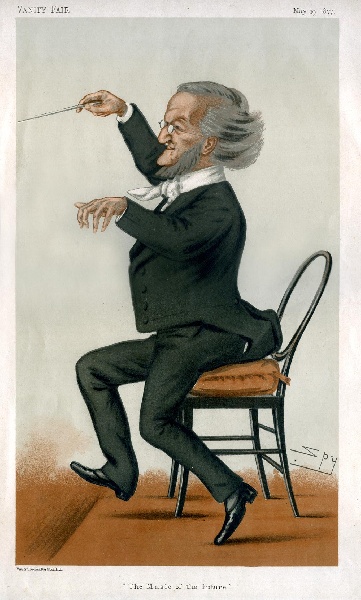

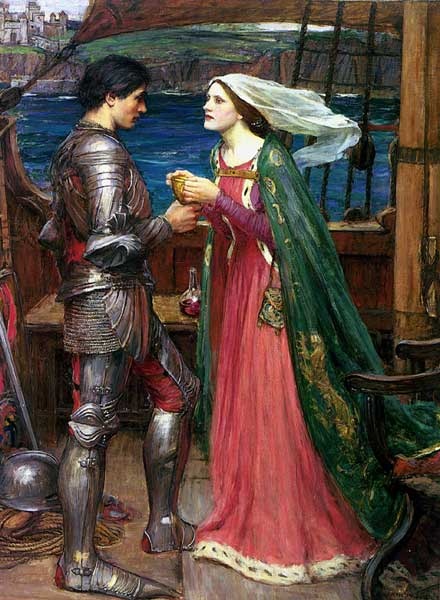

Richard Wagner (1813–83), Prelude and Liebestod, from Tristan und Isolde

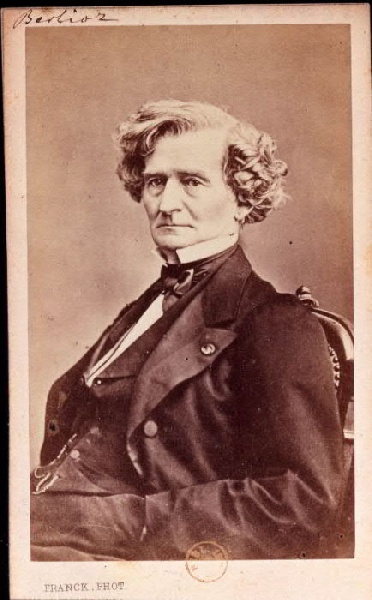

Hector Berlioz (1803–69), Harold en Italie, Op. 16

In recent years the third weekend of the Bard Music Festival has taken place on campus in October. This seems natural enough. For my part I was content to have some time to assimilate the two dense summer weekends. On a typical festival day we heard eight hours of music within the span of eleven hours overall, including a generous selection of aggressive (but certainly not empty) virtuosity like the Paganini Caprices followed by arrangements of them by Schumann and Liszt, both sets of Brahms' Paganini Variations, and a full evening of scenes from Parisian grand operas. Of course this is not like hearing eight hours of Schoenberg, but its sensory demands on the human nervous system are no less intense. Not only was it good to revisit Liszt's music in retrospect, it was pleasant to return to the rolling campus by the Hudson in cool weather, the brown and yellow leaves still on their branches, and to approach Liszt in quite a different atmosphere. School is in session of course, and it's parents' weekend. Although undergraduates were definitely present, the fall audience was considerably thinner than in the summer. As important as these musical programs are at Bard, another event competed with it—a three-day conference on Hannah Arendt, at which Mr. Botstein was also a contributor. For my part, I'd like to believe that the visiting parents couldn't resist the charms of Hannah Arendt. At least there were no football games and taigate parties to distract them. Christopher Gibbs, one of the Artistic Directors of the Festival, told me that the Festival IS the football team.

The Liszt concerts, however, were by no means poorly attended—only in comparison with the packed houses of the summer, and this comparative thinness contributed to a fascinating and most enjoyable phenomenon. In my reviews of the summer events I commented on the excellent acoustics of the Sosnoff Theater in Frank Gehry's Fisher Center. I certainly thought it among the better halls I've heard, but not quite among the very best. I had some reservations about the sound of small string groups and especially the solo piano, as well as a certain glassy hardness in the violins and high choral voices in loud passages. On this occasion those defects vanished. In the afternoon concert (which would have been held in the smaller and equally superb Olin Hall during the summer and was, according to my guess, no more than seventy-five percent full) the various small string groups and the piano were present, clear, and perfectly balanced. In the evening the orchestral sound was also free of any hardness. Dynamic range, presence, balance and fullness were complimented by extraordinary clarity. I will assume that the responsive ensemble playing of the American Symphony Orchestra meant that the musicians could hear each other well. I found myself becoming lost in the beauty of the sonorities, wishing the music wouldn't end. What I heard was truly the quality of a Symphony Hall or a Concertgebouw on a smaller scale. One shouldn't forget that factors like the weather affect the sound of halls and musical instruments, and perhaps our hearing as well. In any case the sound was as impressive as the programming and musicianship which also contributed to this great day of music.

It began with a master class intended to demonstrate Liszt's achievement as a teacher—the focus of his later years. Unfortunately I could not attend it. The two concerts focussed on two closely interrelated problems which served well to sum up Liszt's position in mid-nineteenth century musical life and his relation to his colleagues and his audience. In approaching Romantic music, much of which is so over-familiar we take it for granted, it is essential to remember that most of the major figures knew each other well. In some cases composers were unreserved friends and mutual admirers, like Schumann and Mendelssohn, in other cases the relationships were more complex, as in the convolutions between the insecure and touchy Schumann and the occasionally overbearing Liszt, and later between a generous and helpful Liszt and Schumann's unrelievedly censorious widow, Clara. Then there were Brahms and Wagner...The afternoon of chamber music, titled "The War of the Romantics: Weimar and Leipzig," according to Dana Gooley's lively explanation in his program essay, centered on the debate whether music should purely reflect the traditions contained in harmony and counterpoint, or whether ideas and narratives should be introduced to allow music a broader range, that is, programmatic music. Liszt's prestigious position in Weimar, where he settled in 1848 brought the conflict to a head. Liszt, together with his friend Richard Wagner and Berlioz, led the progressives, with Mendelssohn, Schumann, and Brahms as the leading conservatives. It was the critic Franz Brendel, editor of the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, of which Schumann had been a founder, who defined the situation, calling the progressive group the "New German School," a title which brings together Liszt the Austro-Hungarian, Wagner the Saxon, and Berlioz the Frenchman. This should remind us to forget what we learned in music appreciation class about independent national schools. Berlioz' approach to the symphony sums it up as well as anything. Beginning with the "Symphonie Fantastique" he wrote multi-movement symphonies like Beethoven, the universal model, but he gave the works and their individual movements titles, and the underlying stories played something more than a loose and superficial role in the unfolding of the music. Liszt took up Berlioz' method and developed a somewhat free, single movement form, which he called the symphonic poem. Before I jump ahead to the orchestral concert of the eveining, which included famous and excellent examples of the programmatic efforts of all three "Germans," I should discus the afternoon's chamber music recital, which juxtaposed the programmatic and the pure.

The recital, which was musically on the highest level throughout, began with a rarely-played piano quartet in F minor which Mendelssohn composed at the age of fourteen. The thing to marvel at here is not so much the composer's precocious skill a composer as the fact that he already had some sense of his direction as a composer—evident, I think, in the song-like Intermezzo between the more formal slow movement and final Allegro molto vivace. If not as rich or fully formed as the best of his later work, it is a very attractive piece, in which pensive minor sections preponderate over the quick, energetic rather more than in the more familiar Mendelssohn. The musicians, three students at the newly formed Bard Conservatory of Music and cellist Robert Martin, professor of philosophy and music and Director of the conservatory, brought out the very best in it. The style was set by the refined, pleasingly subdued playing of the violinist, Luosha Fang, a conservatory student from Shanghai, violist Leah Gastler's full, dark tone and expressive phrasing, Mr. Martin's sensitive but solid musicianship, and the truly wonderful pianist Xin Tong of Ziantang, China. Mr. Tong plays with an extraordinary flexibility of dynamics, phrasing, and tempo, as well as a moody spontaneity which is emotionally mature and perfectly suited to Mendelssohn's piece.

Before the intermission, Mr. Tong's teacher at Bard, Melvin Chen, played two of Liszt's strange and wonderful late piano pieces, "Schlaflos, Frage und Antwort" and "R. W.—Venezia" followed by one of his greatest programmatic pieces for piano, "Après une lecture de Dante," which Liszt, turning Beethoven's description of his Moonlight Sonata on its head, called "una fantasia quasi una sonata." This means that Liszt heuristically produced an organic structure from the programmatic content of his work, a reflection on a reading of L'Inferno. An introductory section full of dramatic chords and atmospheric passagework leads up to a musical narration of Dante's meeting with Francesca da Rimini. Here Liszt's melodic line evokes Francesca's pathetic relation of her unhappy illicit love so vividly that we can hear her voice. Only the absence of text separates this music from an operatic scene or one of Liszt's more elaborate songs. When he composed this piece, Liszt was not only deeply engaged in Italian poetry and art, he was in the final throes of his adulterous relationship with Marie d'Agoult, with whom he read the Divine Comedy. Melvin's Chen's performance was technically formidable and keenly alert to the nuances of Liszt's composition. Within the massive sound he produced, Mr. Chen wrought wonders with Liszt's textures, rhythms, rests, and rhetorical pauses. On the other hand he seemed to have little interest in the dramatic aspects of this complex work. Francesca did not lament in a human voice, as she does, say, in Alfred Brendel's quite complete realization of the music. Nonetheless, on a musical level Mr. Chen's interpretation was full of his own grand, severe kind of poetry.

The afternoon continued with Schumann's eccentric and fascinating late work, Märchenerzählungen ("Fairy Tales") for clarinet, viola, and piano, most effectively performed by Renata Rakova, Steven Tenenbom, and Allegra Chapman. Here, without embarking on any specific story, Schumann evoked the flow and atmosphere of folk narrative in each of its four short, contrasting movements. While Schumann apparently tamed his folk-tales for the bourgeois salon, I heard a few wisps of something more primitive. It occurred to me that a performance on period instruments might bring out interesting völkisch aspects of this music. This late work gives the lie to the conservative reputation bestowed on him by Franz Brendel.

The final work was Brahms' great Quintet for Strings in G Major of 1890, beautifully played by faculty members, Ida Kavafian, violin and Peter Wiley, cello, and three more of the Conservatory's gifted and musically mature students from China, Tia Zhuang, violin, Shuangshunag Liu and Liyuan Liu, viola. Kavafian can be quite intense, when the music calls for it, but here she tempered her expressiveness to join in a rather mellow reading, which suits this elegiac piece extremely well. Dynamics were not extreme, and there were some ghostly pianissimi, which came across in the superb acoustics with all the clarity and delicacy they required.

Clearly the Bard Conservatory of Music, which offers "an integrated double-degree program in music and the liberal arts and sciences" is not only an excellent concept, but it has shown impressive results, and so is the exchange program which has brought these students to Bard from China. They give as much as they receive. I invite reader to learn more about this program at its website:

http://www.bard.edu/conservatory

The orchestral concert in the evening had been played once before on Friday. In it Leon Botstein and the ASO brought together the three leading members of the New German School. The concert opened, like so many over the past 140 years, with Wagner's "Prelude and Liebestod" from Tristan und Isolde. Wagner first gave performances of the Prelude in 1860 with his own concert ending, as he was trying to drum up interest in a performance of his new music drama. He first combined it with the Liebestod, which he called "Isolde's Transfiguration," in 1863, when a performance of the complete work on stage was still three years off. It is interesting to note that Liszt transcribed the Liebestod for piano in 1867, but never the Prelude. In the splendid acoustics of Sosnoff, the ASO achieved a Bayreuth-like clarity, as Mr. Botstein led them in a flowing, even rather brisk performance, which was entirely appropriate for this grafted beginning and end. Without five hours of theater ahead, it would be unwise for a conductor to attempt any longueurs. In any case the performance was exquisite in timbre and phrasing, and really quite moving.

There followed a prime example of Berlioz' programmatic symphony, Harold en Italie, which Liszt performed in Weimar and discussed in an essay. First conceived as a viola concerto commissioned by Paganini, who wanted to show off his new Stradivarius, it developed into a symphonic work with obbligato viola evoking the Italian experiences of Byron's Childe Harold. Berlioz transplanted Harold's famous recurring motif into an Italian context from a Scottish one, his own unsuccessful and forgotten Rob Roy Overture. The substantial hybrid work that emerged did double duty following Harold's adventures and moods, while satisfying one's structural expectations of a symphony. Again the hall acoustics, conductor, orchestra did justice to Berlioz' mercurial phrases, sudden changes of dynamics, and complex but transparent textures. Nardo Poy, principal violist with the ASO, played with great finesse and discretion, clearly reluctant to step too far beyond the bounds of the ensemble, an approach which worked well with Mr. Botstein's many-sided view of the music.

The concert and the festival closed with series of old war horses. The First Piano Concerto, Totentanz and Les Préludes, which has perhaps seen better days, but which still remains the most familiar of Liszt's orchestral works. My impression is that it is not played as frequently as it once was. Like elements of Harold, Les Préludes went through a a process of practical adaptation, like others of Liszt's twelve symphonic poems. Originally intended as an introduction to a set of choral settings from his friend Joseph Autran's poem, Les quatre éléments, it appeared in its final version with the indication d'après Lamartine, that is the fifteenth of his Nouvelles méditations. It has been thought that this change was a marketing decision imposed by Liszt's second long-term mistress, the Princess Sayn-Wittgenstein, who thought it expedient to attach the work to a more illustrious poetical name. However, connections with Lamartine's long ode have been demonstrated, and it appears likely that this change of literary inspiration had some connection at least with Liszt's creative process. Liszt, like Schumann, Schubert, Wagner, and others, had a deep connection with letters, as he had for the visual arts, and both are manifest in his compositions. However, his involvement with literature was so complete that his designation of his new musical form, the symphonic poem, shows how much he identified his creative process with that of the poet. If Liszt could conjure up the work of Michelangelo and Raphael in sound, he went so far as to identify himself with Dante, Goethe, and Lamartine, among others, in his musical interpretation of their poetry. Hence the significance of "symphonische Dichtung" is not purely formal by any means.

The piano concerto is often taken as a pure display piece, an example of Liszt's very worst tendencies. Often played as a vehicle for virtuoso pianists with cursory attention to an orchestral score (which does indeed show how much Liszt would learn about orchestration as his work developed) it appears shallow and even gimmicky—above all with that silly triangle in the finale! I won't say that it is an unrecognized masterpiece, but Simone Dinnerstein and Mr. Botstein did it all the justice they could. In this performance the orchestral parts were immaculate and well balanced with the piano. The interchanges between soloist and orchestra could not have been more lively, exploring subtle variations in tone colors as they were batted about between them. As the dreaded triangle introduced the last movement, its master and Mrs. Dinnerstein played in the wispiests of ppp's, producing a truly amazing sound, which they continued to develop as the movement progressed through a range of interesting sonorities. I shouldn't slight Totentanz, which is a fascinating piece in itself. As in the concerto, Mrs Dinnerstein brought just the right balance of supreme virtuosity and musical understanding to bear, and the result was triumphant.

The best thing I can ever say about a musical performance is that it changed my perception of a work I had underestimated, and I doubt I am the only person to have underestimated Les Préludes. In this performance the ASO's lines were lean and alert. Their skill and the hall acoustic made possible an impressive dynamic range, and, as in Harold, extremely delicate pianissimi came through as they should. There was little trace of inflation or pomposity in Mr. Botstein's reading. For the first time, I found it persuasive as music, and the historical connection which emerged from Mr. Botstein's insights were fascinating. Looking backwards—or rather laterally, over Richard Wagner's shoulder—I could see the extent to which his friend's music was present in his mind, above the Tannhaüser Overture, which Liszt had so impressively transcribed for piano. And then there is Berlioz, from whom Liszt learned such an incalculable amount. Looking forwards, it was clear that Mahler had studied Les Préludes in considerable depth. Traces of it appear throughout his works, but nowhere more obviously than in his First Symphony, before he had learned to treat his borrowings more subtly.

The theme which held Saturday's concerts together cut right to the essence of Liszt's position in the musical world of the nineteenth century, and it proved an ideal vantage point to look back over the Festival, not only intellectually, but emotionally, even spiritually, above all in Mr. Chen's piano offerings. Totentanz and Les Préludes may not be among Liszt's greatest works, but these profoundly insightful performances, not lacking in good old-fashioned virtuosic fun, expressed the heart of his stature among his contemporaries and in the process of musical history.