Art and Empire: Treasures from Assyria in the British Museum

Spectacular Exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston

By: Charles Giuliano - Nov 07, 2008

Art and Empire: Treasures from Assyria in the British Museum

The Museum of Fine Arts Boston

September 21, 2008 through January 4, 2009

Catalogue: Edited by J.E. Curtis and J.E. Reade with contributions by D. Collon, J.E. Curtis, I.L. Finkel, A.R. Green, H. McDonald, J.E. Reade and C.B.F. Walker. Published by the British Museum Press. 224 pages, illustrated, with bibliography. Softcover, $39.95

http://www.mfa.org

A visit to the British Museum in London reveals massive installations of the greatest treasures and masterpieces of the Ancient World. It is a by product of 19th century Imperialism when the European powers competed to loot and pillage the vulnerable heritage of once proud but then politically and militarily weak nations.

Most notably, during the era of Napoleonic wars, Thomas Bruce, the 7th Earl of Elgin, while ambassador to the Ottoman Court, managed to bribe the Turks who occupied Greece at the time. He spent some 75,000 Pounds of his own money, most of his personal fortune, to strip the Parthenon of its relief sculptures. Today, they are the greatest prize of the British Museum where they are known in infamy as the Elgin Marbles.

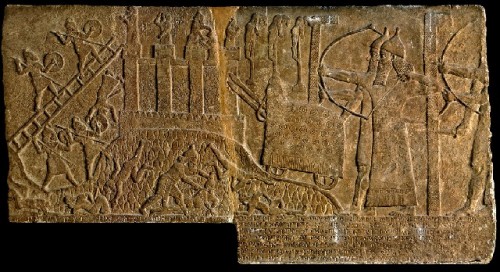

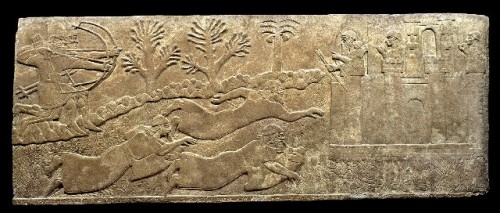

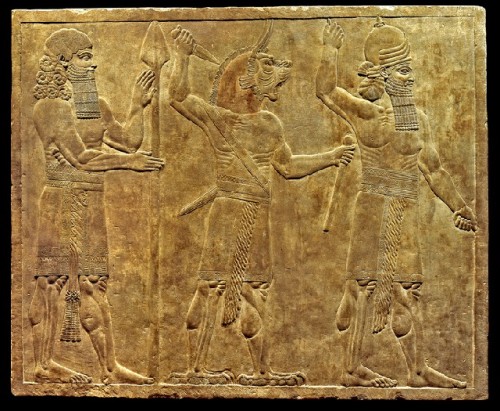

No less spectacular are vast galleries in the British Museum of stone reliefs particularly the magnificent Royal Lion Hunts of the reign of Ashurbanipal, 645-640 B.C. There are also enormous wall reliefs that depict aspects of the brutal art of war. They convey the agit- prop notion of a powerful and ruthless King. These horrific, but poignant, and beautiful images covered the walls of the reception areas of the palaces and were intended to impress and intimidate visiting subjects and ambassadors of distant powers. This was an Imperial art with a specific agenda.

The art and design has helped to perpetuate the reputation of the Ancient Assyrians as brutal, ruthless, and militaristic. While this may have been an accurate assessment they were no worse, one may imagine, than their enemies. There was no Geneva Convention in the ancient world to mandate the proper treatment of prisoners.

The term Assyria is derived from the name of the leading deity Ashur. Originally, a small and landlocked kingdom, located within the confines of the banks of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in modern day Iraq, it expanded to become the largest kingdom of the time. At its peak the territory of Ancient Assyria included all of present day Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon as well as large parts of Israel, Egypt, Turkey and Iran. This came to an end with defeat by the Babylonians in 609 BC. Its great cities were destroyed and abandoned but preserved in Biblical references. The Assyrian Empire became a prototype for the later Babylonian and Persian Empires. These were later conquered and absorbed in the Hellenistic Empire of Alexander the Great which was later taken over by the Roman Empire. In this sense the Ancient Assyrians played an important role in the development of Imperial power, political theory, and administration.

The first European traveler to note the location of ancient Nineveh was Rabbi Benjamin of Tudela in the 12th century. For centuries later travelers commented on the ruins across the River Tigris from Mosul. In 1820-21, Claudius James Rich completed a survey of the ruins. Excavations were begun by Austen Henry Layard who worked in varying locations and campaigns from 1842 to 1851. He made spectacular finds but ran out of funds and made a personal decision to abandon archaeology. In 1851, he was just 34 when he left the field for a mediocre career in politics. Others would follow resulting in vast acquisitions in the British Museum second only to what remains in situ in Iraq or was looted from the Baghdad Museum during the early stages of Shock and Awe.

It is fair to say that, during the era of Imperialism, what did not end up in the British Museum would be looted for the Louvre or by the great German museums. The Pergamum Museum in East Berlin, for example, displays the Ishtar Gate of Babylon. While the greatest depth of Assyrian art is owned by the British Museum, examples of relief sculptures are fairly common in the Louvre, and American museums including the MFA and Met as well as the "study collections" of the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College and the Williams College Museum of Art.

Given the circumstances of the current Iraq War it is particularly poignant and timely to view artifacts of its ancient culture. Such exhibitions are infrequent, expensive, and difficult to negotiate. The current exhibition "Art and Empire: Treasures from Assyria in the British Museum" is the first focused on the art of the Ancient Near East at the MFA since 1965. On every level it is truly spectacular. Short of a visit to the British Museum it is the best possible exposure to this beautiful and often brutal aesthetic.

While detailed depictions of Royal lion hunts are intended to highlight the bravery and skill of the ruler a modern observer will not fail to note that the lion doesn't have much of a chance. It is rather like shooting fish in a barrel. There are also depictions of the king hunting wild bulls with similar results. Some of the most enduring and iconic of these images entail the death throes of wounded lions. In the single greatest masterpiece of this exhibition, a small carving, "The Lioness and the African," Phoenician , 899-700 B.C. the lion has its fangs in the throat of its victim. Perhaps it is significant that the Lion has prevailed over a foreigner, an African.

It is interesting to note the use of dogs, perhaps the ancestors of mastiffs, in the lion hunts. They were used to drive the lions into ever narrowing nets and eventually into pens and cages. There to await being dispatched in a sport of Kings. In the Minoan culture of Ancient Crete a more benign sport, appropriate to that matriarchal culture, was Bull Vaulting. Both men and women participated and the bull survived.

This focus on warfare and death defying blood sports is a signifier of the harsh realities of ancient Mesopotamia. As the catalogue essays point out there were daunting, social, political and even environmental issues. Climate changes and adversity could prevail for centuries. A failure of crops, and loss of game, and shrinking herds of domestic animals caused constant migration, invasion and conquest. The Assyrians practiced systematic Diaspora in which conquered and hostile peoples were relocated to arid and underdeveloped territories. This had an unanticipated impact of interrupting the dominance of Assyrian culture and language (Akkadian) and spreading other traditions, deities and languages such as Aramaic. This resulted in an increasingly heterogeneous Empire with many hostile ethnicities that laid the seeds for eventual collapse and conquest.

Of course, we see exactly that today as the Bush administration tragically approached the conquest and reunification of Iraq as a single national entity. While lopping off the head, literally, of one ruler, Saddam Hussein, it was confounded when dozens of other tribal war lords, terrorists, ethic groups, and religious sects struggled for dominance. It is the very chaos that has prevailed in the region for thousands of years.

So more than an exhibition of stunning and exquisite works this is a history lesson. Assyrian culture prevailed and flourished precisely because of it its brutal repression of enemies. It was expected that the king mount annual campaigns to raid Babylon for its horses or to hold back invasions of nomads looking for better land to feed their people. It was a fragile and complex dynamic which, for a time, created enormous wealth, prosperity and power resulting in superb art and architecture

It took the labor of some 45,000 workers to create the ancient city of Kalhu constructed on 900 acres in Northern Assyria. When it was completed in 860 BC, Ashurnarsirpal II, the self proclaimed "great king, might king, king of the universe" during a ten day house warming entertained 70,000 guests. Today the ancient city is known as Nimrud. Nobody throws parties like that anymore. .