Venice Biennale, Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Part Two

Questions of Value, Art To Go

By: Charles Giuliano - Nov 15, 2007

A curator once described to me what happened when he provided catalogues for free to visitors of his exhibitions. He was dismayed to find them as litter strewn all over the campus. After that he established the rule that there would be a price attached, however minimal, to any publications or printed materials offered to the general public.

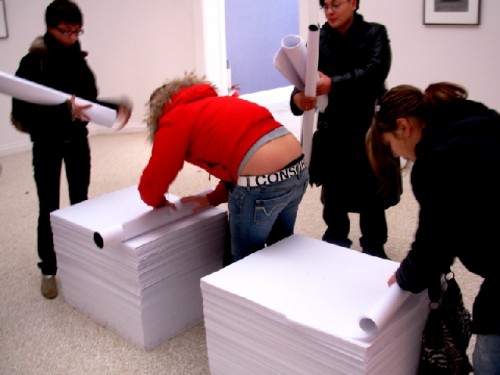

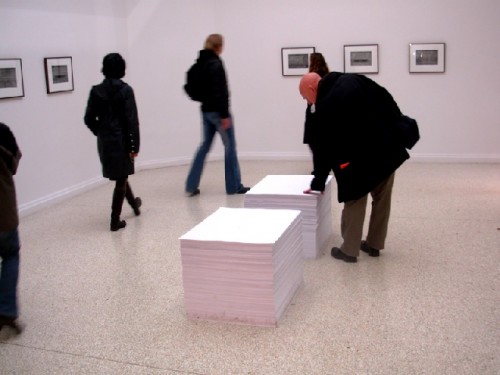

While visiting the United States pavilion of the Venice Biennale I observed a familiar routine as individuals rolled up the free posters stacked in galleries displaying "Felix Gonzalez-Torres: America" curated by Nancy Spector of the Guggenheim Museum in New York. To a lesser extent visitors would reach down for one of the wrapped licorice candies. There was nothing new about all this at least to me. It may have been different to the vast majority of those attending the Biennale; particularly younger visitors who seemed the most enthusiastic about acquiring the "free" art. More than likely the artist and his subversive, politically tinged, conceptual strategies were new to them. Little did they know of or resist the notion that they were responding precisely as the artist, who died in 1996, had intended.

Initially, I was somewhat apathetic in reacquainting myself with an artist and work that I had absorbed with little impulse to revisit. There was a tinge of annoyance that once again the tastemakers had conspired to thrust to the front line work that struck me as politically correct and enervating. My response was along the lines of, yes, I get it, now folks can we move on. Arguably, to more fresh and challenging ideas.

While I acknowledge the significance and contributions of the artist in the context of his moment and generation why are we now lingering over and returning to those issues? Perhaps, I just felt that the work isn't strong enough to be deified to the level of representing the United States in this most prestigious of all contexts. Once again it seemed like an example of the conspiracy theory of a few influential curators, critics and collectors who foist their rarified and politically correct taste and values on the rest us, the day to day grunts, and workers of the art world who rarely, if ever, get to bask in the golden light. Was it yet another example of haves and have nots where I had to exchange worthless Dollars for pricey Euros and travel to one of the most expensive, and beautiful, cities on earth to be handed down yet another lesson? You may argue that getting there is half the fun and that just being in Venice for a week is reward and privilege enough. What the heck more do you want and deserve.? Just shut up, get with the program, and take your medicine.

Surely, those were some of the initial responses that rumbled around in me and I was not alone. The hot line of art world writers, artists and friends shuffling in and out of Venice, swarming onto the crowded vaparettos, conveyed similar responses of being under whelmed by the U.S.A. pavilion.

Then I became gradually more involved in photographing and observing the process of everyone helping themselves to those free posters and candies. Even before we arrived at this pavilion I had been puzzled by a cryptic sign forbidding visitors to enter a particular exhibition with the usual items excluded including back packs but also "posters." That struck me as very odd. But after visiting the Gonzalez-Torres exhibition I came to understand why the artist described his work as "viral." Indeed, the posters were spread all over the grounds of the Bienalle and into the city itself as a kind of infectious disease.

The posters were spotted everywhere and as my own conceptual art piece, so to speak, I became committed to photographing and recording the phenomenon. Astrid became a helpful "spotter" including reminding me to be sure to shoot the poster children while we were in a space that entailed black light which gave the mostly white posters an eerie glow. I later learned that there were billboard scaled reproductions of his generic sky and bird mural, on one wall of the pavilion, in various locations around the city. We failed to encounter any. But folks hauling around the posters were seen everywhere.

So while initially apathetic I kind of flipped over and became a great enthusiast of the work and the means by which it disseminated itself. I came to appreciate that perhaps it was the most successful of all the national pavilions because the work got out into the city and had a life of its own. However ephemeral that leads to another aspect of this critical discussion: Questions of value.

Just what is one of those posters, hauled off by the countless thousands during the run of this exhibition worth, say on E Bay? Can you get a buck for one? How many of them got saved and still survive perhaps pinned to the wall of a dorm room? Of course, this all fits so nicely into the endless art school discussions of the Walter Benjamin essay "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction." This was an essay that I assigned and discussed with students in my former, annual, Avant-Garde seminar at Boston University. Back in 1936, Benjamin initiated a dialogue based on the prevailing technologies of the time primarily film, photography and forms of offset printing. That critical discussion has only accelerated with the plethora of new technologies and even conflates with the very current writer's strike and issues of intellectual property and royalties.

What is the equation between originality and value when you get something mass produced for nothing? At what point do the thousands who rolled up those endlessly supplied free posters conclude that they are worthless? How fast do they become trashed as we saw while visiting the dumpsters next to the outdoor rent-a-potties? I became intrigued and chased after some kids who folded their posters to make paper hats and were exploring other possible applications for these free materials.

It became a kind of game and great fun to continue photographing visitors and their posters. Perhaps the coup of this activity was catching a lady in a mink coat with one rolled up under her arm on the vaparetto. Just what was Her motive for scoffing up a freebie?

Sure. I took a poster. Hey, why not. But I selected the one which is a static, generic, black and white detail of an ocean. This seemed to have more "value" than the ones with just a line of text or a black "funereal" border around an otherwise blank, poster scaled sheet. There was a deliberate decision to limit myself to a single example of the work which I folded and placed in my back pack. It is still there even though we have been home for a week. There are also a few of the licorice candies which I intend to just leave in the backpack forever as a kind of ongoing Feng Shui. I consumed one candy on the spot so the art passed through me rather quickly and may have given me a bit of a sugar rush. More importantly the art got into and invaded me. Which is symbolic and stuff I suppose. A kind of surrender to its subversion even though it was a very conscious and even dramatic conceptual gesture on my part of which I was totally aware,

The notion of attaching value to objects of no value fascinates me. Just what gives a found object or mass produced readymade a monetary equivalent or not? Let us imagine that, as I discussed in the beginning of this text, the curator had assigned a price to those posters and candies. That there was a little store or gift shop where you could buy a poster for, let us say, one Euro. In that case how many would be sold? Arguably, far fewer and in more likelihood they would have a better survival rate. If you pay for something you are more likely to keep it. I plan to frame mine. Not right this minute but eventually. And, as is, in the condition it emerges from my back pack. It will not be mounted or pressed in any way. I hope to preserve its history. And this is not the first time I have taken such an action.

During the last documenta, five years ago, there were "popsicles" by Cildo Miriles for a Euro. It was really hot and they were selling well. We sucked on them and I rubbed my forehead and neck with the sticks of frozen water. But the difference is that I saved the wrappers and sticks and later framed an arrangement of them. My framer used to love my projects. It was always fun to work out the details and often something "free" might in fact cost some serious money to preserve. Like that poster of the wrapping of the Reichstag by Christo. I ripped it off a wall in Berlin and hauled it around to Prague and Vienna. It cost a fortune to frame as the object was thick with layers of posters under the surface and curled up. I wanted to display it as is, not dry mounted flat, and that required an expensive, deep set container.

Today I am proud of that object with its unique, personal history. In the case of the Miriles popsicles I wonder how many have survived and been creatively framed? So the "value" derives from a decision to preserve an object with seemingly no tangible worth. Maybe a dollar or so on E Bay. Eventually auctioned for six figures at Sotherby's as coming from my estate. Or maybe not.