Émilie La Marquise du Châtelet Defends Her Life Tonight

WAM Production of Lauren Gunderson Play

By: Charles Giuliano - Nov 17, 2013

Émilie La Marquise du Châtelet Defends Her Life Tonight

By Lauren Gunderson

Directed by Kristen van Ginhoven

Scenic Design, Julianna von Haubrich; Costume Design, Govana Lohbauer; Lighting Design, Andi Lyons; Composer, Vincent Olivieri; Strage Manager, Norah Scheinman

Cast: Suzanne Ankrum (Soubrette), Brendan Cataldo (Gentleman), Joan Coombs (Madam), Kim Stauffer (Émilie), Oliver Wadsworth (Voltaire).

WAM Theatre

St. Germain Stage

Barrington Stage Company

Pittsfield, Mass.

November 7-24

Founded in 2009 by Kristen van Ginhoven and Leigh Strimbeck WAM Theatre has a mandate to feature women and designate a share of its box office receipts to charities that benefit women and girls. The target this season is $10,000 for six beneficiaries.

While dedicated to doing good work for women and girls WAM Theatre has endured the financial and aesthetic challenges of establishing an emerging company.

By every measure the production of Émilie La Marquise du Châtelet Defends Her Life Tonight, by Lauren Gunderson, directed by Kristen van Ginhoven, is the best to date.

Last night, a Saturday, was an absorbing evening of theatre for a sold out audience. There is another weekend to go but the play has clearly met all of its fiscal and critical targets.

The St. Germain Stage provides a perfect setting for an intimate play. Our proximity is essential to a rapport with the drawing room drama. The minimalist set designed by Julianna von Haubrch forms a receding, truncated V shaped wedge. The slate grey walls are drawn on with chalk to create on one wall a simulation of a library (from which on occasion an actual book is extracted) and on the other the palimpsests of mathematical calculations.

There were two layers of translucent, white organza curtains drawn across the width of the stage. They were used in a variety of ways during the two acts, two hour play.

From this curtain maze, in fits and starts, emerges a spectral figure seemingly in a state of mental disarray as though awakening from a trance. She is the undead emerging from the grave for just one night to weave the tale of her exotic life. Through the course of the evening she will slip in and out of states of being. At times her words will be echoed through an incarnation of her younger living self.

The play presents the remarkable but largely forgotten mathematical and scientific accomplishments of a great woman of the French enlightenment Gabrielle Émilie Le Tonnelier de Breteuil, marquise du Châtelet (17 December 1706 – 10 September 1749).

For fifteen years she was the mistress and intellectual collaborator of François-Marie Arouet (21 November 1694 – 30 May 1778) best know by the nom de plume of Voltaire.

During much of that time, with a combined library of more than 20,000 books and a laboratory for scientific experiments, they resided in Château de Cirey, on the borders of Champagne and Lorraine. The property was owned by her consenting husband Marquis Florent-Claude du Chatelet. Married at 19 she bore him three children. During his long absences as a General she was free to pursue her scientific interests and affairs. Now and then he would visit the chateau.

As we read vividly in Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, among the aristocracy, adultery was tolerated as long as never openly admitted. Then, as in Anna’s case, the woman was banished with no access to her children, or, the cuckolded husband was required to demand satisfaction on the field of honor.

In that regard Emilie and Voltaire abided by the rules.

As a theatrical séance the play is organized in a series of enacted vignettes. These follow the form of ‘The night when…”

For these episodes from the life of Emilie (compellingly portrayed by Kim Stauffer) she interacts with Voltaire (Oliver Wadsworth) and three other actors Suzanne Ankrum, Brendan Cataldo, and Joan Coombs playing a number of other characters.

In the revisionist trope of this project Emilie is presented as a scientific and mathematical genius whose great accomplishments have not adequately been acknowledged. Her translation and publication of Sir Isaac Newton’s Philosophie Naturalism Principia Mathematica from Latin remains the standard version in French. Her The Foundations of Physics written to instruct her young son was a standard textbook for generations. Her greatest individual contribution, in addition to F=MV2 (a precursor to E=MC2), was the 1737 publication of Dissertation sur la nature et la propagation du feu.

Differing from Newton and Voltaire she argued that fire has no mass and hence does not conform to the laws of gravity. In these and other matters she was influenced by the theories of Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz ((July 1, 1646 – November 14, 1716) the German philosopher and mathematician.

Here she differed from and argued with Voltaire who was a Newtonian and denounced Leibniz, in this drama rather archly, primarily because he was German. They submitted their papers to an academy competition separately. While they shared runner up acknowledgements both of their papers were published. For her, it was the first. While, in his lifetime, the remarkable Voltaire published some 2000 books and pamphlets on an astonishing range of topics. He also wrote novels, Candide, and plays.

The thinly disguised agenda of the Gunderson play is to resurrect Emilie as a saint and martyr. When the relationship with Voltaire ended, he publicly denounced her scientific work, she had an affair with the poet Jean François de Saint-Lambert. At the age of 43 she died several days after the birth of their daughter who also died 18 months later. During the pregnancy she feverishly worked to finish her translation of Newton.

This play and its director present Voltaire as a buffoon, misogynist and scoundrel. We see him as a rather sorry sort.

Trust me. He was not.

As a radical thinker he coined the phrase that “The pen is mightier than the sword.” Voltaire was one of the wittiest and most dangerous of the brilliant cadre of philosophes that comprise the French Enlightenment.

During the fifteen years they spent together one may well imagine that their collaborations as lovers and intellectuals were far more complex, subtle and richly nuanced than the caricatures of good and evil depicted in this revisionist play.

While we applaud efforts to resurrect great women, and to explore the impediments that restrained their genius, those good intentions are undermined by the strategy of knocking down and demeaning a giant like Voltaire.

The production also leaves off the stage the context in which the 18th century in France may be regarded as a great age of women. Through their brilliant salons, and in remarkable letters and diaries, one gets a larger picture of how they manipulated and dominated the men who wielded power.

The greatest example of this is Madame de Pompadour (29 December 1721 – 15 April 1764) who as mistress of Louis XV poorly advised him on affairs of state and spent his money so lavishly that she bankrupted France. As such she was a cause of the French Revolution. She died young of total exhaustion.

This play provides no context for Emilie as a courtly woman of her period and what that entailed.

In addition to mastering Latin, Italian, Greek and German she liked to dance, was a passable performer on the harpsichord, sang opera, and was an amateur actress. As a teenager, short of money for books, she used her mathematical skills to devise strategies for gambling. That backfired when, during an evening with card sharps and cheaters, she lost the equivalent of $ I million. With her skill in mathematics she was likely counting cards which today gets one banned from casinos.

To settle the gambling debt she devised a financing arrangement similar to modern derivatives. She paid tax collectors a low sum for the right to their future earnings, and promised to pay the gamblers part of these future earnings

We would like to know more of how Emilie functioned in the famous salons of her era. There is a hint that she cross dressed to attend salons restricted to men.

It was expected of ambitious women that they were well read and versed in the social and political agendas of their time. During salons the brightest women engaged in lively and witty conversation. It was seen as an asset to her husband and a setting for informal diplomacy with guests from church and state. Voltaire was a prize catch for a popular hostess. Nobody wanted to attend a dull evening with boring guests.

In Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence she revealed the crucial significance of launching a successful salon to establish Countess Ellen Olenska in New York society.

During the era of The Enlightenment there was the absurd conceit that it was possible to know a lot about everything.

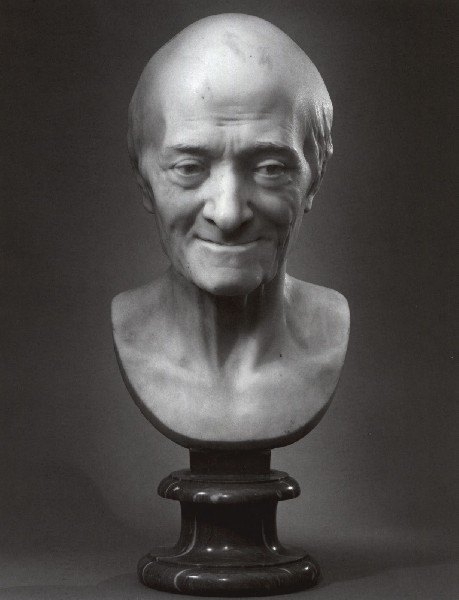

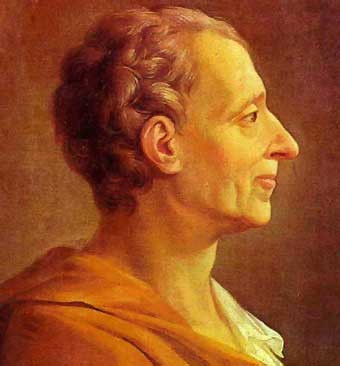

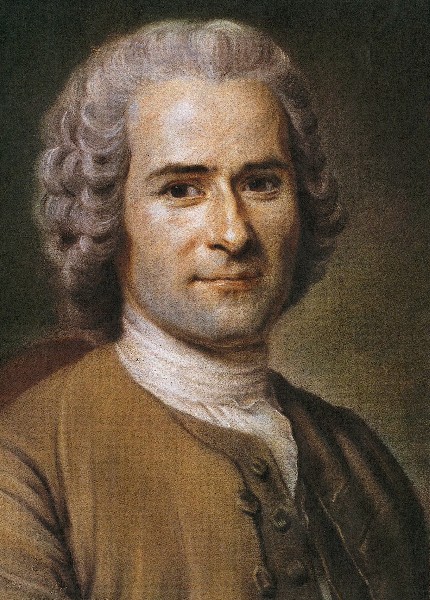

When Denis Diderot (5 October 1713 – 31 July 1784) edited and published his Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers passages were read and discussed during salons. There was also lively discussion of works by Charles-Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (18 January 1689 – 10 February 1755), the naturalist, mathematician and cosmologist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (7 September 1707 – 16 April 1788) and, of course, Jean-Jacques Rousseau (28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) the author of The Social Contract. Camille Paglia argues that it is essential that we read Donatien Alphonse François, Marquis de Sade ( 2 June 1740 – 2 December 1814).

The era of Emilie and Voltaire was a dangerous one for France. They both died before the French Revolution of 1789. The revolutionaries of the Jacobin Club were also inspired by the free thinking of Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677), John Locke (1632–1704), Pierre Bayle (1647–1706) and Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury (5 April 1588 – 4 December 1679).

She criticized Locke’s empiricism insisting that we assume universal principles and innate laws. Without which there is no chain of knowledge, no truth and no numbers. Without principles and laws two and two could just as well add up to four or six.

It’s perfectly fine to approach Gunderson’s play as a work of art weaving together research of historical materials. It is not intended as a documentary. It works well as a drama. Arguably, it is no closer to truth than say last year’s film Lincoln by Steven Spielberg.

For a deep and true understanding of complex issues we can’t rely on an evening of theatre. That’s just entertainment, or propaganda, and not enlightenment. For more on that I direct you to the recent Frank Rich New York Magazine essay on approaches to 12 Years a Slave and Liberal Feel-Bad Movies.

Voltaire described his remarkable lover as "a great man whose only fault was being a woman".

Was that a compliment or a putdown?

This successful but biased WAM production leaves us with a lot to chew on.