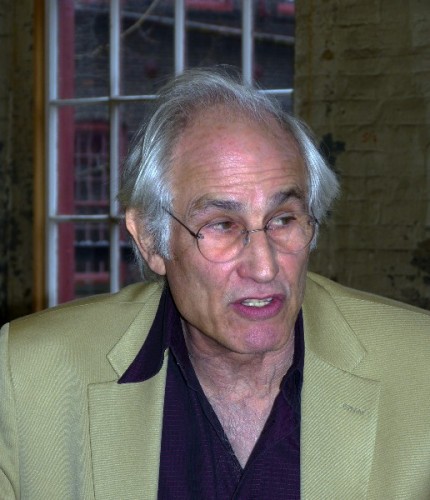

Simeon Bruner on Mass MoCA

Pioneer of Reuse Architecture.

By: Charles Giuliano - Nov 23, 2014

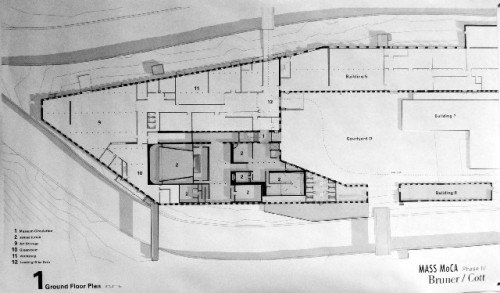

During the recent press conference to announce plans for Phase Three of the development of the Mass MoCA campus we met with the museum’s chief architect Simeon Bruner. In addition to his ideas for the design of building six we discussed the approach of reuse architecture of which he and his firm Bruner/ Cott have been pioneers.

His projects and clients include Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA), Crown & Eagle Mill Housing, Piano Craft Guild housing for artists, Landmark Center, 45 Province Street luxury residential high-rise. Bruner directed the Boston Children's Museum Master Plan and the reuse study for the Wadsworth Atheneum Art Museum in Hartford. He is currently Principal-in-Charge of The Viridian luxury high-rise residential project at 1282 Boylston Street, and the new Lunder Arts Center at Lesley University.

Before founding Bruner/Cott, Mr. Bruner operated his own construction firm. He is the founder of the Rudy Bruner Award for Urban Excellence, a nationally recognized non-profit award for urban architecture and design, and founder of the Bruner/Loeb Forum with the Loeb Fellowship at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. He holds a Master of Architecture from Yale University and a BA in Biology from Brandeis University.

Charles Giuliano You were involved with the original build out of Mass MoCA.

Simeon Bruner Some 27 years now. We were involved with the original plans of Skidmore, Owings and Merrill. We were the mill experts on that one. They envisioned a condominium complex centered around art. In their construct it would become a Club Med of art if you will. Here in North Adams.

CG I don’t recall that.

SB You never heard of that one? You could talk to Joe (Thompson) about that. It’s what got the ball rolling. It was (Tom) Krens’ idea of creating an art complex and finding ways to make it work.

When Krens left (becoming director of the Guggenheim Museum) and Joe took over he really shifted the focus from a box that shows art to a place where things are made and happen. That’s really Thompson’s variant on the original plan.

We did the first plan in 1986-1987.

CG I was one of the first to report on Mass MoCA (for Art News and Art New England). On a Saturday I met with Krens. He had a large ring of keys and took me on a tour of the campus. The buildings were in rough shape with holes in the roof, buckled floors, rodent and pigeon infestation. He spoke with confidence that one day this would all be a museum.

SB Do you remember visiting building five?

CG Exactly. Looking up he said “We’re going to take that floor out and create one large gallery.” Can you recall your first impressions? What shape were the buildings in?

SB There was detritus and dead pigeons everywhere. If you recall it was a rat’s nest. We created open galleries by taking out all those small rooms. It was a mess of rooms with carpets and grass growing out them. They kept moisture in. Windows were broken which helped actually through the removal of moisture. There were rotten beams and you had to watch where you walked. This is the cleaned up version of what used to be. There are still spaces that look like that.

CG At what point do abandoned mill buildings become beyond repair?

SB When the floors become too rotten and the cost becomes too high. That’s what we faced in Phase One. We actually had a fork lift fall through the floor because the floor was so badly rotten. The way that were able to generate really large galleries was to take out the floors.

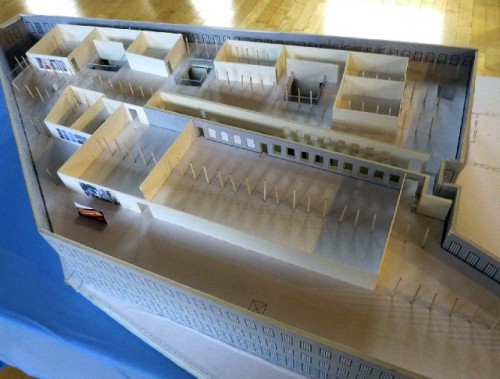

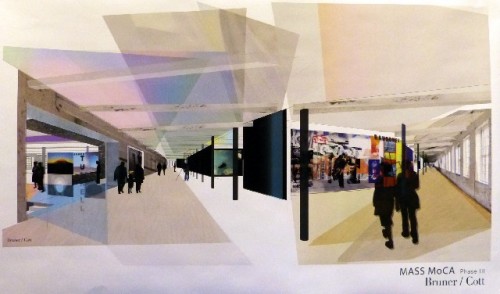

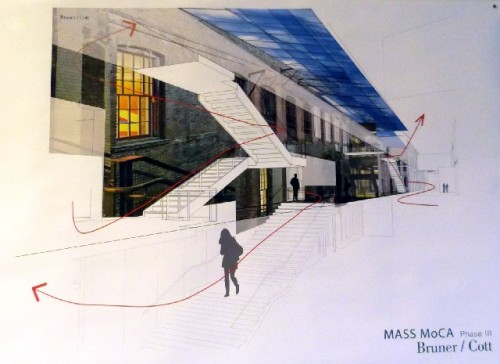

In the new project (Phase Three, Building Six) we have the opposite problem. We have three floors at one acre each. There’s a forest of columns and a thousand windows. Our job is to take these three acres of floors and make them into oases of art. To navigate between oases of (Jenny) Holzer and (James) Turrell becomes an exciting journey.

CG To be the architect of Mass MoCA is almost an oxymoron. The approach is to be non invasive. So much of the texture and flavor of the original mill buildings remains. It’s architecture about what’s not done.

SB If it looks like that then you’ve bought our line. For every one of the spaces we created the original mill didn’t have that. It never had those big spaces. It was just a bunch of small rooms and some work floors. Our job was to make it look like the spaces were there. We created an exciting series of spaces you could walk through and feel good about. And not loose the patina, textures and feeling of history.

It’s the same issues. Space and light. Time and the rhythm of the spaces.

CG It’s often said that reuse architecture is more expensive than tearing down and starting over.

SB It is if you don’t know what you’re doing.

CG The trend of reuse architecture starts in 1976 with Quincy Market by Benjamin Thompson and Associates. From there they went on to Baltimore’s waterfront.

SB We did the first rehab housing in the nation in 1971. It was before Quincy Market and it was before Baltimore. We created apartments in what is called the Piano Craft Building (Boston’s South End).

CG The Piano Craft! That’s yours?

SB We were the architects and developers. I was from a manufacturing family in New Bedford. If you’re careful you can put new in for less. You exploit what you’ve got. You don’t try to make it look new. You make the program for the building not the building for the program.

CG What motivated you to be a pioneer of this approach?

SB Beautiful big spaces. I remember a contractor saying to me about the Piano Craft Building “You can’t put apartments in there. It won’t work.” You can see everything and work with it to make it better.

CG Of course the 1960s approach was to tear it all down. Urban Renewal ruined cities and none more so than here in North Adams. Half of the city is gone and the highway runs through it. There is no incentive to stop and shop. Even now some 120,000 annual visitors to MoCA leave and have no reason to explore the city.

SB Preserving architecture is a much better way to do it and that’s where our heads are now. The building is already there. The history is built in. The scale of the buildings are such that you can’t replicate them.

CG Can you compare Mass MoCA to the Chinati Foundation (Marfa, Texas) or Dia Beacon?

SB At Mass MoCA we’re more interested in preserving the buildings. The scale and texture of the buildings. Dia is more interested in neutering the building.

CG Neutering is a strong term. Can you expand on that?

SB Most of the art that we see here was built in a studio. In spaces very similar to what you see here and does not require whiteout to show the art in the space. The texture of the building enhances the art and works with it. In the way that a white building, an idea that came out of the 1960s, doesn’t work.

CG Marfa?

SB I think I’ll leave it at that.

CG Come on you can’t get away with that. You’re smiling and gesturing. Clearly you have strong opinions.

SB I don’t think architecture has to be white to support art. If you have enough space the work will stand on its own even in a space with texture and (natural) light. It can work in that space.

CG Dia, Marfa and Mass MoCA are most often talked about as paradigms of museums showing contemporary art. As opposed to LA MoCA or ICA Boston.

SB As we put these galleries in it will be interesting to see how they work in the context of what people begin to think about museums. Dia Beacon wouldn’t have happened without Mass MoCA. But maybe Mass MoCA wouldn’t have happened without Dia New York. One of the lessons we learned from Dia New York was that we didn’t have to paint it white to make it work. Maybe Dia Beacon, looking at Mass MoCA, learned that big spaces work also. They (Dia Beacon) carry forward with a 70’s attitude that you have to paint it white to make it happen.

CG Let’s talk in terms of the European kunsthalles like Hamburger Banhof in Berlin or Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid. Like Mass MoCA they are examples of reuse architecture.

SB Or Venice. We went there a couple of years ago and they were showing work in buildings that were falling down.

CG The Arsenale. (Arsenale del Comune di Venezia a complex of former shipyards and armories near the official pavilions of the Venice Biennale.) We saw an interesting Chinese exhibition installed in an industrial building with abandoned boilers. There was a dramatic play between the work and its rough, decrepit setting.

SB We’re doing the same thing. We’re showing art in old buildings. The building is a base to transform into something new. You were here before. You know what Building Four looked like. It’s the same building but a totally different experience.

CG Are you the go to firm when people think of these kinds of projects?

SB I would like to think so.

CG Are you working on other museum projects?

SB We’re working on an art school for Lesley University.

(Lesley University / Art Institute of Boston, New Arts Campus, Cambridge MA

Est. construction cost: tbd

Est. completion: 2012, Size: 100,000 sf

The Arts Campus at Lesley is the new heart of the Art Institute of Boston. A center for art teaching and making, the campus is a crossroads for academic, artistic, and neighborhood communities. The terra-cotta and glass design centerpieces the site's important historic church, initiating a dialog between 19th century religious and 21st century educational icons. An art gallery in the new glass building and a library in the historic church anchor the building at both ends; both are open to the public.

The complex is a transition from Porter Square's large-scale industrial buildings to the smaller, finer-scaled residences and stores along the avenue. The scale and detail of the historic church inform the new building; terra cotta reflects back neighboring brick and clapboard. A glass entry links the church and the new building. Respecting the 19th century building, leaving it intact, and connecting it with the Arts Commons, the entry activates the shared space between the two structures — a dynamic window into the arts community at Lesley.

Designed to LEED Gold standards, the complex exceeds Cambridge's strict new Stretch Energy Code. Building orientation, exterior envelope design, and efficient heat exchange and mechanical systems were priorities.)

This is a gutsy undertaking because there is no other Mass MoCA. Nobody has had the guts to try another one.

CG Economic failures have played in interesting role in American architecture. Because of the British blockade of 1812 Salem, until then a thriving port of the China Trade, collapsed. It is a time capsule for the Federal style of Samuel McIntire. The demise of the whaling industry turned Nantucket, New Bedford, and Martha’s Vineyard into ghost towns. Newburyport thrived during the triangle trade of slavery. The real estate market collapsed but the buildings were preserved. More recently the fishing industry is all but extinct in Gloucester leaving an abandoned waterfront to be developed.

SB Becoming the raw material for rebirth.

CG When Virginia's House of Burgesses moved to Jefferson’s state house in Richmond that saw the decay of colonial Williamsburg. Most of the city was leveled over time before it was rebuilt as a theme park by the Rockefellers.

SB That’s not my field of expertise.

CG Can you respond to the paradigm shift of how what was formerly viewed as old and outdated is now treasured?

SB When we developed the Piano Craft building in 1974 nobody had figured out that it could be used for housing. The idea quickly caught on and now these buildings can’t be found because they’ve been converted.

I remember going to an AIA meeting and at that time restoration was little old ladies in tennis shoes converting train stations into restaurants. Nobody thought that you could take these buildings and find really good uses for them. They’re flexible, grids, and you can do lots of things with them. You just have to adjust your thinking that it’s the building that governs and not the program. All of a sudden you’re doing something, new, unique, exciting with wonderful scale.

CG How much of an uphill fight was it back in the 70’s?

SB People still wanted to tear them down. We did the first mill conversion in the country. We did the first mill conversion in Rhode Island. The first mill conversion in Michigan. People are slow to understand what they’ve got in their own back yard. They would rather have something shiny and new. My kid wanted a motorcycle. He had to go and buy a new one rather than fix up the one in his own back yard.

CG I’m old enough to remember the old Scollay Square in Boston. It was a colorful mix of vaudeville houses, bars, tattoo parlors, flop houses and used book stores. It was leveled to create the new city hall plaza. Did you ever see it?

SB I did.

CG Did you grow up in Boston.

SB No. New York. I went to school in Boston.

CG Where?

SB Brandeis.

CG So did I. Class of 1963.

SB You were in my class.

CG Do you remember me?

SB No.

CG I don’t remember you.

SB I was on the fencing team.

CG Wow. They were good.

SB We went to the Nationals.

CG What was you event?

SB Épée.

CG I was on the wrestling team.

As I was saying they leveled Scollay Square to create the City Hall by Kallmann, McKinnell, and Knowles (1969). It is now considered a brutalist monstrosity. It’s so ugly.

SB It makes a statement. I rail against things that scream ‘look at me.’ But we need these places. It’s a monument. That’s what a city hall should be. I think it’s a fantastic building.

CG We were recently in LA and visited the Getty. It’s huge and monumental but for me the architecture of Richard Meier has become a cliché. What was fresh when he designed the High Museum in Atlanta (1983) now seems formulaic other than grand scale and a dramatic site. But I thought thank God it wasn’t built by Frank Gehry. These trendy hip buildings won’t be in a generation whereas a Mass MoCA will be timeless.

SB These spaces which were built for industrial use are so human scaled.

CG There is an A list of architects that are currently dominant for museum projects. As taste inevitable changes their designs will be less fashionable and even dated as we move forward. That is less true of reuse architecture which retains the look of our industrial past. They are based on a legacy of preserving our heritage.

SB And it works. Speaking of Brandeis we have just worked on the Rose Art Museum. We are hoping to hear from Brandeis in a concept for combining the Rose, the Spingold Theatre and the fine arts/ studio building with a new complex and building. We hope to be among the architects chosen to present on that.

You’ve seen the drawings (for MoCA). This is going to be a great project. It’s going to stand on its own and resonate with what’s been done before. We will be making beautiful spaces. That’s what it’s about.