Legendary Art Dealer Dick Bellamy

Judith E. Stein's Biography Eye of the Sixties

By: Charles Giuliano - Nov 24, 2016

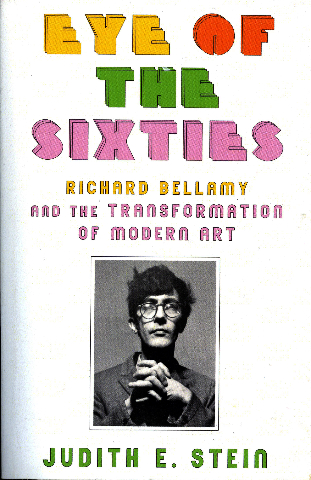

Eye of the Sixties: Richard Bellamy and the Transformation of Modern Art

By Judith E. Stein

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016

384 pages, illustrated

In 2009 Andy Warhol's 1962 silk-screened painting 200 One Hundred Dollar Bills brought $43,762,500 in an auction at Sotheby's in New York. It set the auction record at that time for works by the Pop artist.

200 One Dollar Bills was initially purchased for $1,200 by Robert C. Scull. When Sotheby's posthumously auctioned off his estate in November 1986, the painting was purchased for $383,000 by a private collector.

As the silent partner and backer of art dealer Richard Bellamy (1927-1988) and their Green Gallery (15 W. 57th Street) Scull routinely purchased what later proved to be masterpieces at a 50% discount.

After four years, however, the gallery failed to turn a profit and Scull withdrew support. By then Bellamy, in disarray from decades of self abuse and an indifference to business, let the gallery slide under the management of David Whitney. Other backers expressed interest but Bellamy limped on with other ersatz partners ending as an eccentric private dealer primarily focused on the career of sculptor Mark di Suvero and his rarely visited Oil and Steel gallery.

Ostensibly a collector Scull, was an entrepreneur who from time-to-time deaccessioned and reinvested in emerging artists. That started with a famous auction of works by seminal abstract expressionists. Viewed as arguably unethical and certainly in bad taste it has become common practice in today's art world.

While Scull lamented that he lost interest in the work the conventional wisdom is to buy low and sell high. It is not unusual today that works acquired go straight to warehouses there to age and accrue in value for eventual resale in the secondary market.

Scull, who was colorblind, may have been crude and crass but he was also ruthless, clever and prescient. Particularly when it came to building his fortune through his wife Ethel's family taxi business. With unique acumen for marketing the fleet, the first in NY with two way radios and etiquette seminars for its drivers, it was dubbed "Scull's Angels."

Having missed the boat on buying works by the seminal, post war, abstract expressionists Scull, through Bellamy and gallerist Leo Castelli, got in on the ground floor of emerging artists. He often went along on studio visits where he bought on the spot.

Their marriage ended in a much contested divorce but the Sculls made remarkable acquisitions. They owned other important Warhols such as Ethel Scull 36 Times (June-July 1963) which was created by multiple silk-screened images of her created in a photo booth.

Other major works included James Rosenquist's monumental F-111 (1964-65), in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, Jasper Johns' 0 Through 9 (1961) which sold in November, 2004 for $10.9 million. The Sotheby Parke Bernet sale of fifty works from the Scull collection in October 1973 included Johns' Ballantine ale cans titled Painted Bronze (1960), now in the collection of the Kunstmuseum Basel.

Robert Scull is but one of the many legendary artists, collectors, poets, dancers and bohemians that cavort through the lively and riveting book "Eye of the Sixties: Richard Bellamy and the Transformation of Modern Art" by art historian and raconteur extraordinaire Judith E. Stein.

At the center of a maelstrom of the art of his time was the improbable, enigmatic, playful and self destructive, merry prankster Bellamy. We learn that his parents were doctors but his Chinese born mother never practiced.

Careening through Provincetown in the 1940s, by default, he catapulted to New York where he earned starvation wages running the cooperative Hansa Gallery. An upstairs neighbor proved to be critic and then graduate student Barbara Rose. Running buddy Ivan Karp was, until they were ousted, co-director, whatever that means, of Hansa Gallery.

They shared a passion for discovering talent and mounting ground-breaking group shows that evoked serious reviews and respect in the field but few sales. Artists they discovered prospered by moving on to more commercial dealers like Sidney Janis, Leo Castelli and Arne Glimcher. They changed the field by offering stipends and advances on sales. Green had to match to keep pace but that put the gallery into debt.

When Scull negotiated to back them for a gallery they brainstormed for a suitable name. Not surprisingly Jolly Roger was rejected as was Karp's idea OK Harris and Bellamy's Oil and Steel. Karp instead joined Castelli but they both later founded galleries with those pet names.

There was a parting of ways when Castelli took on Dan Flavin over the objections of Karp. In this instance Ivan was dead wrong.

An artist quipped that Oil and Steel meant that Bellamy would oil up collectors and then steal from them.

Stein's book is rich with anecdotal narrative. Bellamy and his circle, friends and lovers (everyone was shagging everyone) come alive. Not just art history this is a book that broadly appeals to anyone interested in an era when making art was not about theory, fame and fortune.

Ultimately, Bellamy emerges as a tragic figure precisely because of his lack of interest in commerce. His indifference to promoting sales, however, infuriated artists who otherwise adored and respected him.

In the immediate Post War era that Irving Sandler dubbed The Triumph of American Art the art world was tiny and insular. Galleries for contemporary art and serious collectors were rare. Museums, for the most part, showed little interest in aquiring works by living artists.

Many of the Abstract Expressionists were middle-aged drunks by the time their work began to sell. Their epic struggles, however, engendered messianic idealism. Fueled by the high priests of criticism, Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg, abstract art achieved iconic and sacrosanct status.

Stein begins her art world narrative in post war Provincetown, the gay and Portuguese fishing town, a summer camp for New York's artists. There Bellamy formed lifelong associations with emerging Figurative Expressionists like Jan Muller and the painstaking, reductivist abstract painter, Myron Stout. This part of the book, including reference to the seminal Forum '49, had me starved for more. Most books about P'Town, particularly that incredibly fertile period, are stiff and stodgy lacking her lilting narrative wit and insight.

After the Third Generation of Abstract Expressionists the artists that interested Bellamy had Oedipal relationships with their paternalist icons. Many of the Figurative Expressionists, Realists and Pop artists started with but rejected gestural abstraction.

Perhaps the sangfroid treatment of the Provincetown era reflects Stein's reliance on research rather than direct involvement. The book jolts alive when she is an embedded player in events that she reports. From the Hansa period on we feel like a fly on the wall of so many incidents, happenings, performances, exhibitions, openings and events. She conveys what artists were thinking and feeling as the art world exploded from Pop to Minimalism and Pluralism in the wacky 1960s. Stein gives us the disco beat and pulse of the zeitgeist with Bellamy, by then, seemingly curled up in a drunk and stoned ball as the party rocked on.

In its seven years, 1952-1959, the cooperative Hansa Gallery represented a number of important artists including: Robert Beauchamp, Miles Forst, Paul Georges, Wolf Kahn, Alan Kaprow, Jan Muller, George Segal, and Myron Stout.

The Green Gallery introduced Claes Oldenburg and Dan Flavin as well as Jo Baer, Ronald Bladen, John Chamberlain, Jean Follett, Ralph Humphrey, Mark di Suvero, Donald Judd, Ellsworth Kelly, Alfred Leslie, Patricia Pasloff, Larry Poons, James Rosenquist, Lucas Samaras, Daniel Spoerri, Richard Stankiewcz, Tom Wesselman, Robert Whitman, Neil Williams and Jane Wilson. Through Green Scull became a major patron of Earth Works including those of Walter De Maria.

In an arrangement with Noah Goldowsky, after Green Gallery closed, they shared a space in which Bellamy dealt out of a tiny room. From there he brokered the first sale for Yoko Ono. He worked with Richard Serra and Bruce Nauman who ended up with Castelli.

While Stein rightly celebrates Bellamy as the "Eye of the Sixties" one might add that he was its heart and soul. Ultimately, he did not survive the tidal wave of commercialism, greed and megalomania that marched down the Odessa steps from the 1970s to the fouled nest that prevails today. The idealism that Bellamy personified is signified by that baby carriage careening into oblivion.

While his personal life was an unholy mess, as conveyed by the author, Stein also detailed his meticulous and pristine installations. The chaos of his persona was mirrored by the refinement and order of the exhibitions. Perhaps it is a trait he inherited from his mother and her exotic collection of precious objects from her native China.

Most of all Bellamy had a gift for sculpture. Not just a dealer he truly became the curator of De Suvero. That culminated in exhibitions and catalogues he organized which went beyond selling the work. He took up photography in order to document the work. Settling a debt with the sculptor it was partly paid by handing over the archive.

There were women in his wife, Shendi his first wife, and their son Miles. Then on an off with Sally Gross. There were numerous affairs and then a May/ September love with a grad student Barbara Flynn. She had a small gallery and for a time they lived and worked together.

Although tormented and complex, particularly as a father to Miles, it is fair to conclude that Bellamy was respected and loved by the artists who knew and worked with him.

It was poignant and sad to put down this fascinating book. She depicts a too brief window when art really mattered. Stein has fleshed out a biography of a remarkable trickster, coyote and shadow catcher.