Le Corbusier's Carpenter Center at Harvard

Master Architect's Only North American Building

By: Mark Favermann - Nov 29, 2008

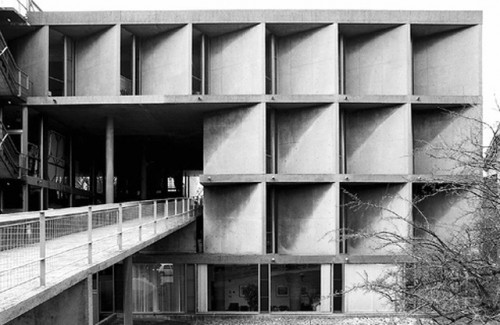

Walking down Quincy Street away from Massachusetts Avenue on the south side of Harvard Yard, one is struck by a distinctive cast in place concrete building that has none of the old Cambridge red brick or shingled traditional detailing.

This is a work of singular 20th Century Modernism glaringly intersecting with traditional, 19th Century Harvard architecture. This structure is the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts designed by Modernism's high priest, architect. and design icon, Le Corbusier. It is significant on many levels.

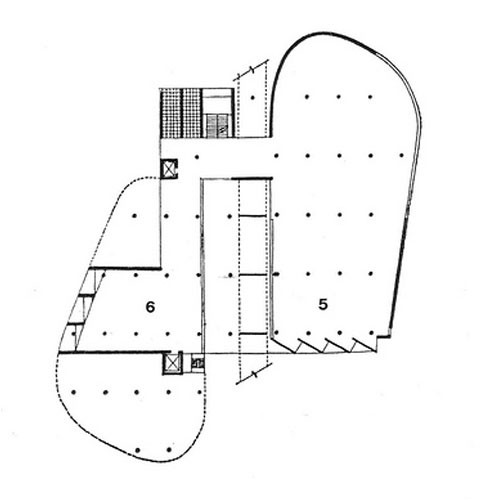

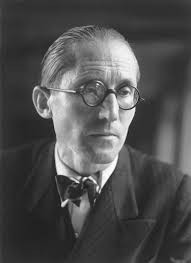

In a book Le Corbusier at Work: The Genesis of the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts by Eduard Sekler and William Curtis, Harvard university Press, 1978, Sekler discusses the singular purpose which animated all of Le Corbusier's work: organic and geometric shapes.

These shapes can be found in his paintings that were done in the 1920s and carry through his furniture, artwork and architecture. To Le Corbusier, all the arts were conscientiously progressive. Sekler sees Harvard's Carpenter Center as the culmination of a lifetime of painting, sculpture and architecture.

Another essay in the book by Barbara Norfleet is based upon a survey of the building's users. Here, she suggests that the majority feel that security issues prevent free movement throughout the structure that does not allow clear perception of the building as a whole. Thus, strangely according to Norfleet, the intended composition of the Carpenter Center can only be experienced through privilege or secretive maneuvering. It is part of Harvard's private campus and therefore limited to students and invited guests, for God sakes!

This almost quaint quasi-Marxist view of egalitarian sharing is both dated and a bit silly. A better consideration is that the Carpenter Center was conceived as a whole and to view it in separate, disconnected sections does not allow for appreciation of its imaginative and accessible configuration.

A third essay by Art Psychologist and theorist Rudolf Arnheim investigates the notion of creativity. Like Le Corbusier himself, Arnheim claimed that there are rules for creativity. Le Corbusier's painting, sculpture, furniture and architecture demonstrate this search for rules. Architectural historian, William Curtis, wrote an essay on the design of the building, how it was conceived, flows structurally, and what makes it distinctive. Comparing Arnheims 'rules' to Curtis' analysis makes a provocative, nicely academic comparison.

Other Modernist structures at Harvard do not seem to resonate exteriorally visually and internally functionally as well. Other Modernist buildings on the Harvard University campus include the Harvard Graduate Center (1950) by the Architects' Collaborative and Walter Gropius, Harvard Science Center, by Sert, Jackson and Associates (1973), Gund Hall, The Graduate School of Design by John Andrews (1972), Holyoke Center (1966), and Peabody Terrace Graduate Married Student Apartments (1964) again both by Sert, Jackson. These do not "work" anywhere as well as Le Corbusier's Carpenter Center.

Like all great figures, Le Corbusier worked hard on building his own personal myth. He was very private, almost secretive. He projected an almost austere, very controlled lifestyle. This was not altogether true. A recent lecture by Nicholas Fox Weber, given at the Carpenter Center, humanized Le Corbusier. Weber published a thorough biography about the architect, "Le Corbusier, A Life," (2008) published by Alfred A. Knopf Inc.

His research has brought to light several provocative aspects of his life. One was that Le Corbusier had an affair with 1920's entertainer Josephine Baker. Another was that he had a long-term mistress in Connecticut. And a third was that he shared virtually every aspect of his life with his mother until old age. Who would have thought?

Half a century later, the Carpenter Center's rear pedestrian bridge has been elongated and now is attached to Renzo Piano's expansion and rehab of the venerable Fogg Museum (to reopen in the Fall of 2014), its next door neighbor. I wonder how Corbu would have felt about this?

Le Corbusier was known for his priestly pronouncements. "A house is a machine for living" is well known. Less known is his comment that "architecture is the learned game, correct and magnificent, assembled in the light." This can be said about his Carpenter Center which is distinctive both at Harvard and in the United States. In a way, it is an iconic structure memorializing the high priest of Modernism, Le Corbusier. After over fifty years as part of the campus, it somehow fits at Harvard University. Like the great university, its whole is as great as its parts.