The Collegiate Chorale Performs Moise et Pharaon

An Unexpected and Glorious Rossini Opera on the Exodus

By: Susan Hall - Dec 01, 2011

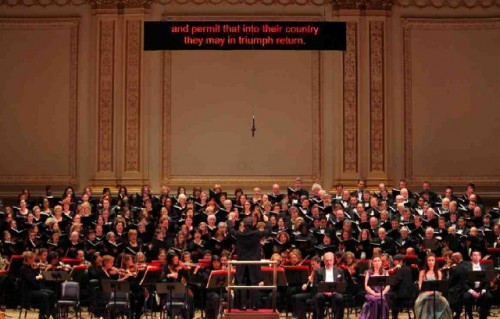

The Collegiate Chorale

Carnegie Hall

November 30 2011

American Symphony Orchestra

James Bagwell, Music Director and Conductor

Moise et Pharaon by Gioachino Rossini

James Morris Moses

Kyle Ketelsen Pharaoh

Angela Meade Sinaide

Eric Cutler Amenophis

Marina Rebeka Anai

Eliezer Michele Angelini

Gingeer Costa Jackson Miriam

John Matthew Myers Ophide

Christopher Roselli A mysterious voice

Rossini? Moses? In the earliest version of Moses, Naples went wild with enthusiasm. Stendhal, who hated the soprano Isabella Colbran almost as much as Biblical subjects, went to the theater prepared for a good laugh, and wrote after the performance that he had never been so moved. In England, subscribers to the King's Theater were so aroused that the manager of the theater was proposed for membership in White's Club. For the first time Rossini received appropriate compensation for his work, seven times as much as he got for Tancredi.

James Morris was magnificent as Moses. What singer wouldn't take a minute to settle into the role, perhaps the one closest to God, and more terrifying than Wotan. In aria, recitative and ensemble Morris sang with dignity and grandeur.

Mixed reactions to Marina Rebeka in Don Giovanni earlier this fall seemed unwarranted as she sang Anai, the Jewish love interest of the Egyptian prince sung by Eric Cutler. In a happy ending Romeo-and-Juliet scenario, in which the girl gets to escape with her own family, their duet is delicious, even though this pair is the main cause of trouble between the Pharaoh and Egypt which precipitated the problems presented in the opera. Rebeka is a Faith Geier artist, a beneficiary of the program set up by The Collegiate Chorale to help deserving singers whose careers are budding.

The chorus, particularly singing the Jews, was exultant, supplicatory and even menacing. Some 200 strong, hearing them in the auditory bliss of Carnegie was overwhelming. When the Jews and Egyptians sing together, the Jews kept the upper hand in the drama in the spirit of the music.

The quintet in the second act and the quartet in the third are fascinating ensemble compositions, sung beautifully in this performance. Michele Angelini showed us why he is a young tenor to watch. This wonderful lyric tenor takes the most seemingly difficult runs and ornaments as though they were easy.

Angela Meade in the small role of the Egyptian Queen, brought down the house. Hers is a voice for the ages, so lush and pure, filling every corner in Carnegie with ease because it is so naturally large.

If resistance to the opera's mounting in today's houses comes from the apparently stand-and-sing needs of the opera, think Aida, which still is magnificent, even as the great Johan Botha stands and delivers. The Collegiate Chorale makes a compelling case for a current full production of the opera.

Kyle Ketelsen, magnificent in a Muti-led Berlioz last spring, took on the Pharaoh with his big, yet sensitive bass. You sat up and looked twice when Ginger Costa-Jackson, a mere slip of a woman who closely resembles Angela Jolie, started to sing Miriam, Moses' sister. She has an extraordinary, rich mezzo, and while she at first touchingly trembled next to the cool, experienced Morris, she became justifiably confidant as the performance went on.

If this concert version of Moses seemed to disappear unexpectedly at the end, you could understand why watching the DVD of a Riccardo Muti led version. In the DVD, planks that evoke waves rise up to let Moses and the Jews pass through and then clamp together to keep the Egyptians out. Maybe Robert LePage got his ideas for the Machine in the Ring from Moses. The difference: in fact the Red Sea parts and then closes without a glitch. In one of the early productions, people sitting in the rafters could not see this effect. The entire device was moved up so they could have a view. When this happened, the audience in the orchestra could watch the boys who were moving the oars back and forth from under the sea.

The beautiful prayer of the final act was written for the first draft Moses after Rossini was overcome by the need to cover up the boys on stage by composing a solution. He may have written it quickly, but not while talking to his friends as is sometimes reported. The effect of its beauty is hard to understand today, but in its time it was highly original. The changes of key and use of the chorus were completely novel. In Naples, 40 women of “excessive musical sensibility” had attacks of “nervous fever or violent convulsions” when the prayer was sung. I was too swept up in the beauty to see how others were reacting at Carnegie.

The only gripe heard about this opera is that there are too many apostrophes to God. However with our unemployment stats, manufacturing heading south even in China, governments state and local broke, the Euro Zone imploding, such apostrophes seem apt. In any case, created by Rossini, they are gorgeous.

The Collegiate Chorale performs its important mission with such class. Next up in February, not to be missed performances of Bruckner's Te Deum and Tippett's A Child in our Time.