Mongolia Part Two

Khovsgol Lake and Gobi Desert

By: Zeren Earls - Dec 01, 2016

Delighted with our first ger camp experience of nomadic felt tents amidst the green pastures of Terelj National Park, we returned to Ulaanbaatar for couple of nights before venturing northwest to the Lake Khovsgol region near the border of Russia. Our second visit to the capital city was a welcome opportunity, as 45% of Mongolia’s just-under-3-million population live in Ulaanbaatar, contributing to its vibrancy and rich cultural life.

Our urban exploration started at a shaman’s ger, identified by a fetish tree on the roof, adorned with people’s wishes on ribbons and topped with the Mongolian Soyombo symbol, an alignment of flame, sun, and crescent signifying unity. Our hostess, a woman in her 30s and the daughter of Mongolia’s national shaman, shared her story of how she had become a shaman herself. As a young girl she had been very ill with kidney problems, with no cure in sight after being in and out of hospitals. One night she had a vision that spirits had entered her body and that in order to be cured, she needed to put cow kidneys on her back right over her own kidneys and so, the following night she wrapped onto her back cow kidneys, which had been delivered to her in a thermos to keep them warm. By the morning, she was all cured, convinced that she should become a shaman.

The woman proceeded to show us all the things she had had to acquire with her father’s help to become a shaman. The owl and eagle feathers from which her hat was made represented wisdom and strength respectively; the metal studs on the back of her costume kept out bad spirits; the color, shape, and type of the many rings on both her hands had all been dictated to her by spirits. Feathers, all considered sacred, hanged from the ceiling. A golden eagle in the ger received donations on her behalf for services. As we sat quietly, the woman prayed, eyes closed, before going into a trance and playing her mouth organ. Then, putting on her colorful ribboned costume, feathered hat, and boots, she played the shaman’s tambourine, its stretched skin displaying images of an eagle, sun, and mountain, all in all an eye-opening experience.

Entering through the three-arched gateway of the city's Naran Tuul open air market provided a very different kind of experience. A vast array of produce, displayed under multi-colored parasols, stretched as far as the eye could see. Shoppers were beckoned by a labyrinth of tented stalls stacked with bolts of fabric, clothing, hats, saddles, and material to make a ger. The stalls were lined with traditional leather boots with upturned tips in the color of one’s choice.

A theme park provided the setting for an enjoyable lunch, which constituted of beef wrapped in bacon within a dough crust, beautifully presented with an accompaniment of vegetables and salad. Then, courtesy of the restaurant, we rode the Ferris wheel, which offered a bird’s-eye view of a castle with turrets, in the middle of a pond connected by bridges to the rest of the park, which included a children’s playground and a panoramic view of the city.

Meeting the owner, who had inherited the family business for traditional hand-made instruments, we learned the steps in making horse-head fiddles as he walked us through the process. Beech wood is used for the sound box, which is cut, sanded, and stained before attaching the tuning pegs, which are carved into the form of a horse’s head. In the final stage the bow and the sound box are strung with horse hair. A spirited demonstration of music convinced me to purchase two CDs – recordings by a master horse-head fiddler and by an ensemble of folk musicians – which were delivered to me later at the hotel, as only instruments were sold at the workshop.

In the morning we flew to Moron, the administrative center of northern Mongolia’s Khovsgol Province. At the end of the one-and-a-half-hour flight we were met by the drivers of four station wagons, who were to deliver us to the Ashihai Camp on Khovsgol Lake at the foot of the eastern Sayan Mountains. The drive took several hours with occasional stops, including lunch. Traveling on a dirt road that cut through green pastures of various shades, we stopped at a scenic spot by the lake, where horses were cooling off in the clear, shimmering waters.

Another detour took us to the “deer mounds”– rock heaps identified as 3500-year-old sacrificial sites near burial grounds. The headstones near the mounds have bas-reliefs depicting deer horns in profile, hence the name. Of the 1100 mounds found to date in the region, including sites in Kazakhstan and Russia, 900 are in Mongolia. Back on the road, we drove by herds of yaks, cows, and goats complementing the pastoral tableau. Finally, our lakeside ger camp emerged, enhancing our anticipation of the three-day adventure that awaited us at this beautiful resort.

The camp staff led us to our individual gers, explaining that the washroom facilities were walking distance from our sleeping quarters. The charming red interior of my ger with its water view made up for the scanty facilities. As I walked about the grounds, the vast lake, which is the second most voluminous freshwater lake in Asia and holds almost 70% of Mongolia’s fresh water, donned a splendid silhouetted evening shoreline.

In the morning, we rode on horse-back behind a middle-aged master herder and his five helpers, including his 10-year-old son, who kept tight control of our reins. I wore a black metal helmet strapped under my chin, with no camera in my hand to distract me, as we rode for about an hour along the shores of the lake. Some locals dared to go into the 50-degree water, while others enjoyed breakfast in front of their private tents. Ducks in the water, horses with their colts, and yaks grazing in the pasture completed the panorama that I enjoyed from my high perch.

Following lunch, we traveled in two small motor boats to the northern shore of Khovsgol Lake to visit a family of reindeer breeders belonging to the Tsaatan people, who live a nomadic lifestyle in the coniferous forest, or taiga. With the aid of a makeshift ramp made of logs, we disembarked onto a rocky shore, within sight of grazing reindeer topped with elaborate horns, unique to northern latitudes, and dwellings that resembled teepees. Our young hostess, a descendant of a migrant herding tribe from the Tuva region of Russia, welcomed us in her yurt, made of trees covered with animal skin, where she was living with her fourteen-month-old baby. Herds of reindeer roamed the grounds against the scenic backdrop of the lake and welcomed the opportunity to eat from our hands. Nearby a young man carved pictures with a sharp tool on the deer horns, enticing us to buy them and we did.

Heading back to the camp, we stopped at an ovoo – sacred stone heaps used as shrines – to make a wish by adding a rock to the mound. We climbed up the ovoo, which was on a hill, then circled it counterclockwise three times to ensure a safe onward journey. Those unable to climb high stopped at a small rock pile midway. Back at camp, some of us joined our young trip leader, Damda, on a hike for a panoramic view of the lake. The rigorous climb, which recorded 5.5 miles on the health app of my smart phone, was worth it for the view! Afterwards the warm weather turned breezy, bringing rain all through the night.

We left at 7:45 next morning in four cars, negotiating deep ruts on dirt roads soaked with rain, in time to help milk the yaks of a herding family on the Mongolian steppe. Upon arrival, we entered a pen crowded with yaks and calves of all sizes, with babies suckling at their mothers’ breasts. Two young women showed us how to milk by sitting very close to one side of the yak and beginning to pull at the nipples with both hands in an up-and-down rhythmic motion until milk started to drip. Palms covered with the white liquid, I helped fill a bucket, which was delivered to the ger where the owner, a retired truck driver, lived. We met the elderly couple and their two grandchildren, who were visiting during summer vacation and otherwise lived with their parents in the city, attending grade school.

On a wood-burning stove our hosts prepared yak milk tea and served it in bowls along with home-made bread and clotted cream. We then helped make yogurt over the stove by ladling boiling milk out of the pot and slowly pouring it back again to aerate it, which aids the curdling process. Both the tea and the yogurt were delicious, the latter a bit sour. Accustomed to non- or low-fat dairy products back home, I rediscovered the rich taste of full-fat dairy! With an insight into the austere lifestyle of this nomadic family, who were so dependent on the long-haired yak for virtually all basic needs, such as milk, food, shelter, and clothing, we bade them goodbye.

Our next exploration was to the nearby town of Khatgal, where we visited a boarding school for students coming from more than 10 miles away. Since our visit coincided with the school’s summer vacation, we were unable to observe students in the classroom. Instead we saw their small sleeping quarters, which had four cots to a room, and the gym, where some boys were practicing Mongolian-style wrestling, in which a wrestler loses the match if his elbow or knee touches the ground. The winner of that encounter celebrated by waving his arms like a bird in flight, symbolizing strength. In the meantime, groups of students were competing in various corners of the gym for the best origami project or the best bridge constructed by tying together small sticks.

Nearby, a local bakery, an ice cream shop, and a restaurant, all run by a retired engineer, beckoned with its specialties. At the bakery, we watched pans of dough move through a long wood-burning oven, dispensing baked bread every seven minutes. At the restaurant, we enjoyed fish soup, salad, and a traditional main dish of noodles with ground beef. Yak milk ice cream with blueberry sauce complemented the tasty meal.

Although it was a windy day, we then walked to the harbor, where Mongolia’s only cargo ship is docked. It used to travel from one end of Khovsgol Lake to the other before roads were built. The lake, 85 miles long and 25 miles wide, is 5397 feet above sea level and 860 feet deep, receiving water from 90 rivers. Despite the blustery weather, all the souvenir stalls at the shipyard were open; many tempted us with their well-crafted wool items. I purchased a pair of socks embroidered with the image of Mongolia’s two-humped Bactrian camel.

Back at camp for our final night and dinner, we enjoyed yak milk ice cream once again, this time with chocolate sauce. Three members of the staff put on a show for us, ranging from throat singing accompanied by horse-head fiddle to dances inspired by deer and horses; the former involving fast footwork, the latter gallops and trots. The evening ended with a teepee-shaped bonfire by the lake.

Waving goodbye to the staff in the morning, we left for Moron for our return journey to Ulaanbaatar. During the two-hour ride to the airport, we stopped by a wooden bridge that provides vehicular access to Russia 160 miles away. The bridge, though only twenty years old, looked well-worn from heavy use. At the airport, our Mongolian Hunnu Air flight, delayed by one hour, finally left for Ulaanbaatar. Upon landing at the end of an hour-long flight, we drove 30 miles west of the city to catch the horse races of the annual two-day Naadam Festival, which includes competitions in wrestling and archery in addition to cultural programs.

Leaving our bus at the parking lot, we took open-air shuttle vans to the race grounds, which were a feast for the eye. Brightly colored modern tents were intermingled with traditional white gers. People young and old with children in tow, most in elegant traditional regalia, headed to the bleachers to watch the races. Some like myself and other tourists, lined the grass up front for a closer view of the horses as they approached the finish line. The age requirement to enter the race is six years of age for jockeys and three years for horses, determined by a dental exam. As 300 qualified horses bolted into view one after another, it was exciting to see very young jockeys at the head of the pack. We exited the grounds quickly afterward, as we had an early morning journey south to the Gobi Desert.

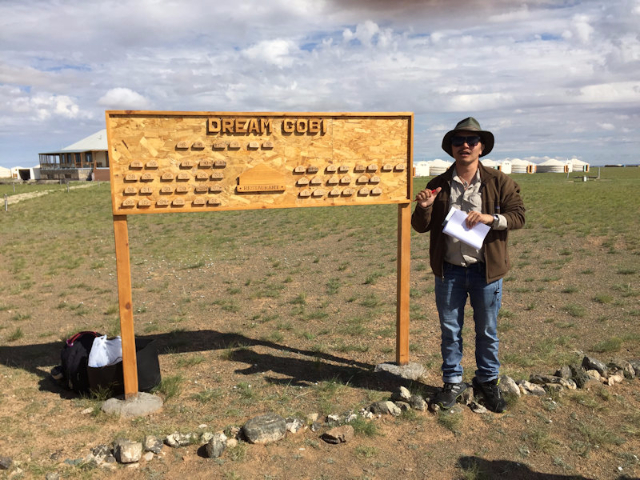

Awakened at 4 am, we left the hotel at 5:20 with a bagged breakfast for a 6:55 flight to Dalanzadgad, 340 miles south of Ulaanbaatar. Upon arrival at the new Gurvan Saikhan airport, we were met by four drivers, who ushered us to their cars. Following a brief stop to pick up snacks, we entered the desert on a dirt path that cut through green and gravel plains surrounded by faraway hills. Sitting next to the driver, I fell asleep from having slept so little the night before and from staring at the seemingly endless scenery for two hours. We reached the Dream Gobi Tourist Camp shortly before 11 am, in time to watch the official opening ceremony of the Naadam Festival on TV.

The staff met us with a pitcher of cold juice, although the air felt quite cool, reminding me that we were in the world’s coldest and northernmost desert. A large concrete weight suspended from the ceiling of my ger to keep the roof from flying off confirmed the effect of the wind. It was comforting to know that each ger had an adjoining washroom, allowing us to refresh quickly and file into the basement of the main lodge to watch the ceremony.

Following the opening speech by President Tsakhiagiin Elbegdorj, highlights of Mongolia’s 2000-year history unrolled before us on the screen. Professional actors playing khans and queens, along with dancers, circus performers, soldiers, and teenagers representing current pop culture exuberantly revealed the country’s accomplishments: the unification of its tribes by Kublai Khan, the founding of the empire, the arrival of Buddhism, and today’s independent Mongolia. The ceremony, which lasted several hours, ended with a sky-diving show. We spent the rest of the afternoon enjoying the solitude of our desert surroundings.

In the morning, the same four cars took us on a bumpy road to the Yol Valley, whose name means “vulture” in Mongolian. A protected area within Gurvan Saikhan National Park, named after the mountain range to the east, the valley is a narrow gorge noted for its glacial ice, which is six miles long in the winter. Although we were there in July and the ice had started to melt, we opted to see what was left of it. Following a footpath, which soon gave way to a stream we had to cross by hopping back and forth over rocks, we reached the dripping ice bed in the shadow of the towering mountain. By the time we trekked back, my iPhone had clocked seven miles. We stopped at another camp midway to ours for lunch and returned to our base somewhat tired, though invigorated by the morning’s walk. I joined the camp staff, who were watching the Naadam wrestling championship on TV. Wrestling is a major sport in Mongolia. Over 1000 wrestlers vying for the championship symbolized the country’s strength.

On our last day in Gobi, we visited a nomadic family with three boys, who helped in the breeding of Bactrian camels. They offered us camel milk tea, fermented camel milk, and camel milk butter served with small chunks of fried dough. We then learned the process of making felt from carded camel hair or sheep’s wool, which is wrapped in cloth, dipped in water, soaped, and squeezed several times before being pounded. The process is repeated until the felt is quite flat. Previously dyed felt pieces are then added in order to complete a design over the background piece. We bought several finished pieces as souvenirs; mine was a desert landscape depicting gers under a blue sky.

Riding the family’s Bactrian camels was a treat. The two-humped beasts carried us to the dune region of the Gobi Desert, only 5% of which is covered with sand. Climbing up and around, we explored the dunes on our own, then went to a nearby camp for lunch.

Our final treat of the day was a visit to the Flaming Cliffs, known in Mongolian as “Bayan-Zag”, meaning “oasis of saxaul shrubs”. The area is famed for the first-discovered dinosaur nest and fossils, found here by a US expedition to Central Asia led by paleontologist Roy Chapman Andrews in the 1920s. Affiliated with the American Museum of Natural History, it was Chapman who nicknamed the site the “Flaming Cliffs” for the ochre color of the escarpments, which had been at the bottom of an ancient sea 60 million years ago. We walked amidst the sculpted cliffs. Just as we climbed the peak, it began raining hard; we got soaking wet walking back to the van. Tired of dodging large puddles, our driver left the muddy path, opting to make new tracks over grass plains. While back at camp, a hot shower took care of my chilled body, it took days to dry out my shoes.

For our departure to Ulaanbaatar, we had to arise at 2 am owing to the two-hour trip to the airport. However, the early flight allowed us more time for sight-seeing in the city, which we started at Zaisan Hill with its panoramic view. Climbing 200 stone steps, we reached the top, marked by a monument to the Russians and Mongolians who fought Japan in 1921. The 95th anniversary of the 1921 Peoples’ Revolution was marked in elegant Mongolian calligraphy on the slopes of the hill. The 360-degree view from the hill highlighted the new Mongolia, with its high-rise buildings stretching all the way to the surrounding sacred mountains.

The Zanabazar Museum of Fine Arts is a small building with strikingly beautiful collections of Mongolian art from prehistoric times through the early 20th century, including works by Zanabazar, a 17th-century artist and the country’s first spiritual Tibetan Buddhist leader. The tantric paintings and silk embroidery alone are well worth the visit.

A trip to the State Department Store was an opportunity to buy unique Mongolian crafts and fashion items. After visiting all four levels, I purchased a blouse sequined with the yin-and-yang symbol, a traditional wool vest, a felt neck scarf centered with a wide band of Chinese silk, a white quilted felt piece embroidered with colorful silk threads, and a suede cushion with a quilted felt center band.

The city was under tight security and all hotels were booked because of the 20th ASEM summit in Ulaanbaatar to promote cooperation between Asia and Europe. We had to drive out to Terelj National Park to spend our final night in Mongolia, arriving at camp in time for a farewell dinner. Damda presented each of us with a traditional Mongolian blue silk scarf. In recognition of my 20th completed trip with Overseas Adventure Travel, I also received two thank-you gifts an engraved brass bowl and a horse-head fiddle desk ornament.

Ten of the fourteen in our group left for Siberia the following day with memories of Mongolia that will live on for a very long time.