Padova/ Padua: Giotto's Capella degli Scrovegni

Fifteen Minutes of Fame

By: Charles Giuliano - Dec 03, 2007

For tickets call 049 2010020 (the number in Italy) or e mail below.

info@cappelladegliscrovegni.it

During a summer in Italy, in 1975, as a Kress Fellow through Boston University, I met a young Scottish woman, Phillipa Torrie, in a church. While I was admiring a painting over the altar she informed me that it was the only Rubens in Venice. A conversation ensued and for the next few days she was my companion and guide through the alleys and bridges of Venice to its best affordable restaurants and even the right day to visit the Peggy Guggenheim Museum. The great collector was alive at the time and kept odd hours. I swear that was Peggy sitting at the dining room table with her pooches when we visited.

On her day off from tending to that Rubens painting in the church Phillipa suggested that we take a train to Padova which is only a half hour from Venice. That was such a long time ago and during this recent tour of Northern Italy I was determined that Astrid and I might refresh those faded memories. But so much has happened since those freewheeling student years now more than three decades ago. While much progress has been made in restoring Italy's countless treasures they have also become more carefully controlled and less accessible. Which we experienced, a few years ago, when visiting Santa Maria del Carmine, in Florence, to view "The Tribute Money" by Masaccio. We were fortunate to wait just a couple of hours. It was March and off season. But this time we had no luck obtaining tickets for "The Last Supper" by Leonardo de Vinci in Milan. Make sure to book well in advance if you hope to visit these restricted sites.

In Padova/ Padua we were more fortunate. Our concierge made a call and we had a couple of time options for the following day, Sunday. We arrived with a half hour of leeway for our appointed booking. There we found a group clustered around the entrance to the church with its priceless frescoes by Giotto di Bondone (1267-1337) and his workshop. We explored the adjacent museum and viewed a video. Eventually, we were admitted to a holding area, every seat occupied, and for fifteen minutes, were shown another video.

As part of the restoration of Capella degli Scrovegni the holding area is climate controlled. When the doors are closed the fifteen minutes allows for sealing and cleansing the air before that group is admitted into the chapel. There you are allowed precisely fifteen minutes to view the paintings with their elaborate plan and iconography. There is so much to absorb in such a brief amount of time. Which is never enough. Then you are ushered out and the next group is brought in.

When we booked a reservation I had no idea we would be limited to just fifteen minutes. That may be fine for a tourist but hardly adequate to an art historian. Particularly having taught the material to generations of undergraduates relying on memories of that visit in 1975. When I conveyed my dismay about these "Fifteen Minutes of Fame" a former BU professor and mentor, Carl Chiarenza, e mailed a response that he had purchased back to back slots and was able to stay for a half hour. A great idea. But also expensive as the visit isn't cheap and converting from Euros to Dollars makes it even more costly.

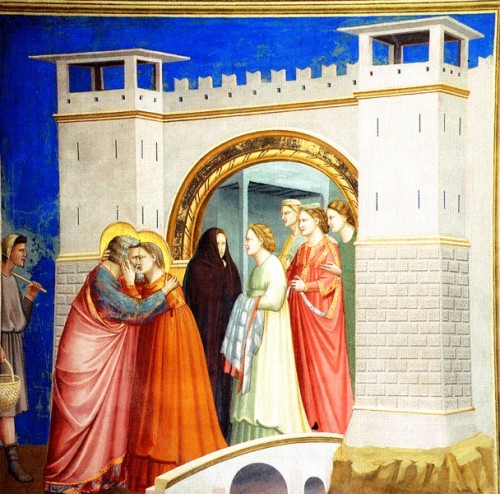

The church was dedicated to Santa Maria della Carita on the Feast of the Assumption in 1303. Giotto, then the most distinguished and sought after artist of his generation, was hired by the banker Enrico Scrovegni, His father, Reginaldo, was a sinner and userer whom Dante described encountering in the Seventh Circle of Hell in his epic poem The Divine Comedy. Until Masaccio painted "The Tribute Money" on the walls of Santa Maria de Carmine, with its famous reference of "Render Unto Caesar," usury, or lending money for profit, was a mortal sin.

During the middle ages the lending of money was the business of non Christians. Of course, by the Renaissance, Christian Bankers, like the Medicis in Florence, were anxious to get a new interpretation of scripture. Hence the passage that describes Christ as paying his taxes equated bankers, in the Biblical sense, with Caesar. Another tactic, taken by Enrico Scrovegni on behalf of the condemned soul of his father, was to bribe the church with a great act of charity. Hence, the dedication of the chapel with its stories of the Life of Mary and the Life of Christ to Santa Maria della Carita. Mary as the personification of Charity.

The tomb of Enrico is located in the apse. In the Last Judgement, on the end wall, Enrico is depicted presenting a model of the chapel to the Virgin. These Donor motifs are a frequent aspect of medieval and Renaissance art. The patrons of works of art and public charities want to make it absolutely clear that they are seeking absolution. There is a familiar pattern in which blood money turns to charity in later generations. It is a way of purifying the family name from the ruthless deeds of the founders of great fortunes.

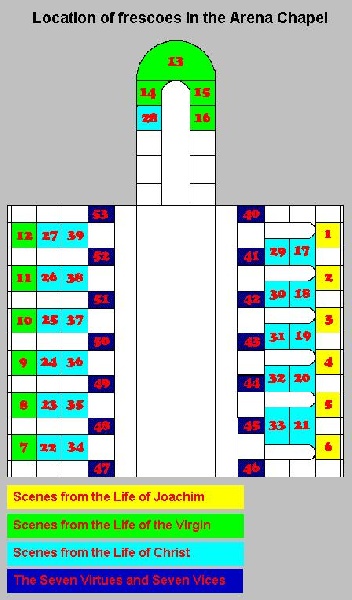

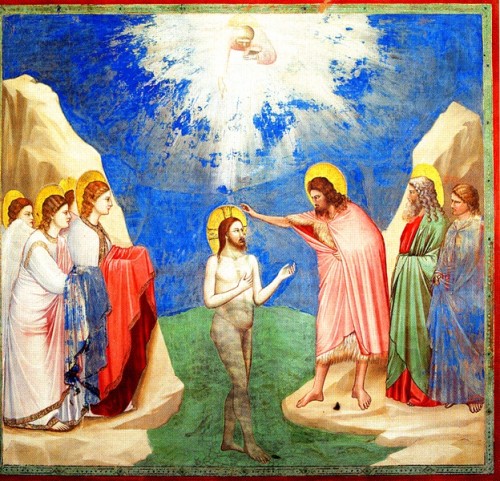

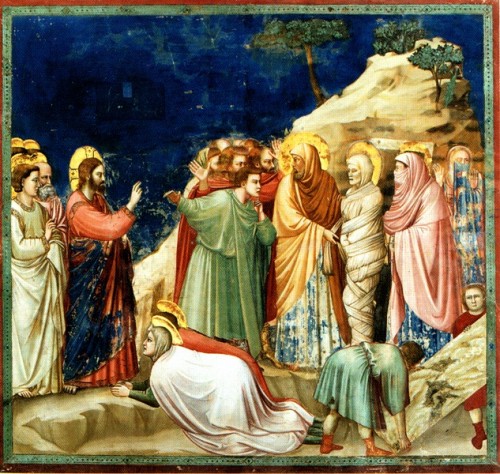

The chapel is rather small but it is remarkable that Giotto and his assistants were able to complete the project in just a couple of years by 1305. As a master of a workshop Giotto developed the design scheme and delegated much of the execution to assistants while unifying the compositions with his deft brush. In a fresco cycle only as large an area of plaster that may be completed in a single day is applied to the wall. Water color is applied to the wet plaster and sinks into and bonds with the surface. Some changes and highlights may be added when the plaster is dry with egg tempera in the manner called a secco. But this paint is not bonded with the plaster and may prove to be fugitive particularly when restored or cleaned. By counting up the giornati, the areas of a single day of work with their characteristic borders, art historians are able to calculate just how much time was involved in painting a fresco.

Another observation of a fresco cycle, particularly one that takes a couple of years to execute, is that the style and experimentation of the artist is often quite remarkable. There is a growth process and often works at the end of the project are stronger in technique and expression than the more cautious and conservative efforts in the beginning. Giotto was 38 when he completed the work in Padua and would live for another 22 years. So the cycle may be viewed as his mid-career masterpiece. While he belongs to the Middle Ages there is much on view here that places him on the cusp of the Renaissance. Of course the critical difference is that he did not know the rules of true perspective. The first to apply them, and the founding Renaissance master of painting, would be Masaccio (1401-1428).

In the medieval tradition the settings and architectural detail in Giotto's paintings are more like stage props than what Leone Battista Alberti published in 1435 as "Della Pictura" his treatise on perspective and painting techniques. Alberti described a painting as a view or vedute as though looking through the rectangle of a window out into nature. While Giotto never achieved that sense of perspective there is a remarkable quality of naturalism and volume, as well as human expression. and emotion. He was the first to move out of the rigid formulas and caricatures of medieval representation. It is what so informs the cycle of stories depicted on the walls of the Scrovegni Chapel.

Or, during our recent visit, so much to absorb in such fleeting minutes. You just try to take in as much as you can. Particularly, that brilliant rich blue that he used for the sky. It is everywhere and still remarkably fresh and intense. Of course one is reduced to the visual equivalent of triage. You concentrate on the most famous and riveting parts of some 34 panels, the Last Judgement, and the Allegories of the Vices and Virtues. The most compelling details are "The Kiss of Judas" or the "Pieta." There is also much to study in the "Last Judgement" particularly as it related to Michelangelo's fresco of the same theme in the Sistine Chapel. It is in this aspect of the cycle that one most vividly understands how Giotto is medieval and relates to Dante Alighieri (1265-1321). Giotto was born just two years after Dante.

It is also important to realize that in the medieval context of their time the paintings of Giotto and the poetry of Dante were very real and vivid to their respective audiences. While today we view their work as art, for their audience, it was more about the rewards of heaven or the eternal damnation of hell. For Enrico Scrovegni, who built the chapel and paid for Giotto's masterpiece, it was about buying his way into heaven. Let's hope he made it.