Nelson Algren Bio by Mary Wisniewski

Wrote The Man With the Golden Arm

By: Nancy Bishop - Dec 05, 2016

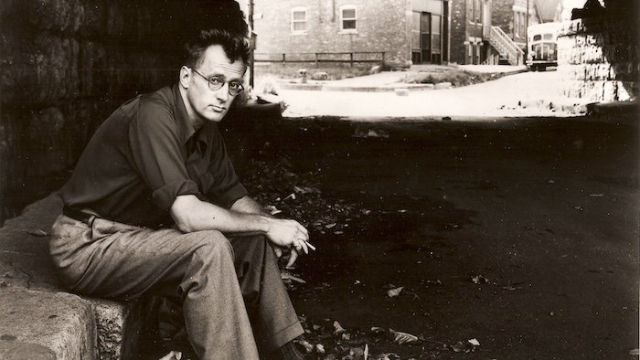

Nelson Algren was a star in Chicago’s bright literary firmament, but his light dimmed in the years after he won the 1950 National Book Award for The Man With the Golden Arm and acclaim for a few other works. A new biography by Mary Wisniewski explores Algren the man and Algren the writer and how one influenced the other.

Wisniewski, a Chicago journalist, grew up in the Polish immigrant neighborhood known as Polonia where Algren lived and wrote for much of his life. She knows and understands the neighborhood that influenced Algren’s writing. His novels and stories are naturalistic and sympathetic to the lives, sorrows and crimes of the down and out.

Algren loved Polonia for its seedy nature, rundown bars and streets inhabited by hookers, drunks, bums and drug dealers. He probably would be disgusted to find that Polonia has been transformed into trendy Wicker Park. One of the buildings where he lived on Wabansia was demolished for expressway expansion. All that’s left of Algren in Wicker Park now is a wrought-iron fountain dedicated to him in the “Polish triangle,” a pigeon-infested little park at the intersection of Division, Ashland and Milwaukee. And fans and scholars of his work gather for Algren birthday celebrations, with readings and speeches, every March at the Hideout on Wabansia.

He was born Nelson Ahlgren Abraham in 1909 in Detroit. His parents were nonobservant Jews from Chicago. They moved back to Chicago in 1913, living first on the south side in the Park Manor neighborhood and later in Albany Park. Algren graduated from Roosevelt High School and the University of Illinois with a major in journalism.

His best-known books are the short story collection, Neon Wilderness (1947), the novels Never Come Morning (1942), The Man With the Golden Arm (1949) and A Walk on the Wild Side (1956), plus the book of essays, Chicago: City on the Make (1951).

Never Come Morning, the story of Bruno and Steffi, a killer and a prostitute, was condemned by the Polish Roman Catholic Union and the Polish American Council for its “vicious attacks” on “loyal American citizens of Polish birth or extraction.”

Perhaps the most famous words that Algren wrote are from Chicago: City on the Make.

“Yet once you’ve come to be part of this particular patch, you’ll never love another. Like loving a woman with a broken nose, you may well find lovelier lovelies. But never a lovely so real.”

Wisniewski’s very readable biography is colorfully written, highlighted by detailed plots and character descriptions of Algren’s books. And she doesn’t spare the negative details of Algren’s life: his marriages and affairs, his gambling and drinking, and his inability to handle money.

Algren: A Life asks us to consider some opinions often posed about Algren.

Why isn’t he considered part of the family of Chicago literary greats along with Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Sandburg, Bellow and Brooks? Algren wrote novels and stories, some of which are considered brilliant, like The Man With the Golden Arm and A Walk on the Wild Side, as well as the book of lyrical love-hate essays, Chicago: City on the Make. Some of his books were out of print for years. (Algren was in the first class of inductees into the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame in 2010.)

Did his reputation decline because of the shoddy filming of Golden Arm? Algren hoped it would be a film masterpiece to match his acclaimed novel but he thought the 1955 Otto Preminger production was of such poor quality that he refused to have his photo taken in front of the movie poster, according to Art Shay, his friend and Chicago photographer. Because of this film and the way his books were marketed, Wisniewski suggests, Algren became known as a pulp fiction writer.

Was he famous because of his storied affair with Simone de Beauvoir, the Paris intellectual who came to love Algren and the city by the lake? She made many visits to Algren’s apartment and visited the bars and dives he liked. She also spent time with him at the house he owned later in Miller Beach, a neighborhood of Gary. But Beauvoir was the lover and intellectual partner of existentialist writer Jean-Paul Sartre, who ultimately took primacy in her life.

Her affair with Algren was dramatic and tempestuous but hindered both by the Paris-Chicago distance and her relationship to Sartre. She’s buried in a tomb with Sartre in Montparnasse Cemetery, wearing a ring Algren gave her. Algren made several trips to Paris, but his travel was hindered because his passport was denied twice because of his political activities.

Despite his several marriages and many relationships, Algren never achieved the traditional life he seemed to want–a wife, children and a home where he could concentrate on his writing. He lived and wrote in Chicago from the 1930s to the 1970s. In 1980, he moved to Sag Harbor, Long Island. He died there of a heart attack in May 1981. His gravestone carries these words, usually attributed to Willa Cather:

THE END IS NOTHING

THE ROAD IS ALL

Two recent documentary films tell Algren’s story. Algren by Michael Caplan was screened at the 2014 Chicago International Film Festival. Nelson Algren: The End Is Nothing, the Road Is All, directed by Mark Blottner and Ilko Davidov, released in 2015, is available on DVD.

Wisniewski is a reporter for the Chicago Tribune and previously was an investigative reporter for Reuters, covering Midwest crime and politics. She also wrote for the Chicago Sun-Times and Chicago Lawyer. She’s active on the Nelson Algren Committee, which hosts the annual Algren birthday celebration.

Algren: A Life, published by Chicago Review Press (2016), is available in hard cover for $30 or as an e-book for $15 from online and retail booksellers. The book includes copious notes and a useful bibliography of works by and about Algren and the Chicago literary tradition.

Reposted courtesy of Third Coast Review.