Jeremy Denk Performs The Well Tempered Clavier

Bach is Still Full of Joy at 300

By: Susan Hall - Dec 06, 2021

Jeremy Denk performed “The Old Testament of Keyboard Music,” Bach’ s Well Tempered Clavier (WTC) , at the 92nd Street Y in New York. The artist selects works to which he can bring new insights. Bach, he sensed, was trapped by the Glenn Gould performances in the mid-20th century. Audiences found the neuroses Gould implanted in Bach suitable for the century’s mood. They also appreciated the humming he added to the piano notes. Other performers flatten the work to sound more like a harpsichord.

Whether or not this performance history serves the composer, he is again central to performed music. He always has been. Bach never disappeared from the music scene, and Mendelsohn’s resurrection of the St. Matthew Passion was no turning point.

Denk gives a performance like Bach’s own. Bach’s students report that the composer, also the greatest keyboard performer of his time, loved to play the WTC. Heinrich Gerber wrote in 1724. “This latter work (WTC) Bach played altogether three times...with his unmatchable art, and my father counted these among his happiest hours when Bach, under the pretext of not feeling in the mood to teach, sat himself at one of his fine instruments and thus turned those hours into minutes.”

Listening to Denk, one hears the depth, the whimsy and play Bach found in notes. Power and virtuosity, and infinite technique produce heartbreaking melodies, and pure abstraction. Denk seems to have fun. There are LOL moments unusual in the concert hall.

The core treasure is Bach’s counterpoint, explored more exhaustively by him than by any other composer.

In counterpoint, the voices of piano lines speak to each other. Denk’s hands erupt in scales scampering in unison, in harmonic relationships, and then in opposition. These relationships intrigue the listener. In them, we hear dissonance, switches from major to minor, and the myriad of small but important details the composer has written.

Beethoven only came to appreciate the joy of Bach at the end of his composing career. Then he mixed deep interior searches with pure pleasure, a pleasure evident in each note struck by Denk. He describes tumbling, somersaulting, leaping and boring in on the beauty of the arpeggio. For an encore, he repeated the C major Prelude, the first of 24, which sends a simple arpeggiated line off an anchoring note. Never has this work seemed silkier, in its first iteration at the beginning of the program, and in its farewell bid at the end.

From the first addition of his own decoration at the beginning of the program we are reminded that performers were not tied to the notes on the page in Bach’s time. Works were to feel improvisatory. While Denk dashes some off, they never feel unimportant.

He sets out to wrest Bach from ‘sewing-machine style’ which purged Bach of vigor and juice. Gould is not the answer because he removes the logic. Somewhere an idea is proposed, no matter how small in each work, and by the end, around three minutes later, a world is built.

Bach is careful to display of a ‘subject', sometimes as small as one note. (Denk prefers the term ‘idea’ to subject or theme). What Denk makes clear are these three and four and five note ‘idea’ nuggets are repeated, converted and changed from major to minor. Denk claims that Bach is missing the sex and angst we all need in our music, but “how strange the change from major to minor” gets close to both in his take.

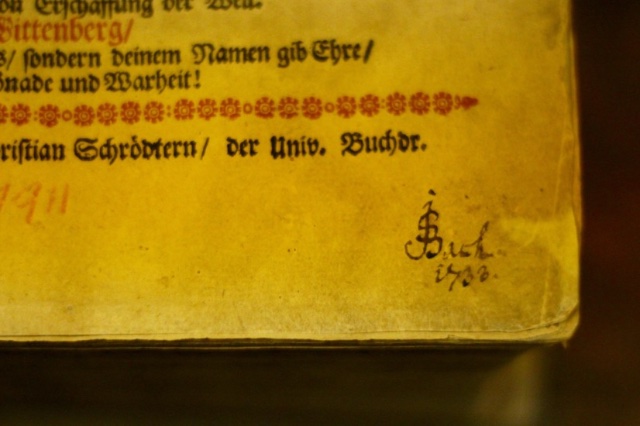

Bach is different from other composers. His ironclad logic leads to excruciating beauty, and religious ecstasy if you will. The debate over Bach’s person religion is perhaps resolved in his personal, notated Bible, which is available for view at the Concordia Seminary in St. Louis, Missouri. There is no question that he was a man with a mission. Goethe wrote that God had placed him on earth.

All of this may be a bit excessive, but the sheer joy of listening to Denk is not. This fertile mind brings to each of the little pieces insights which match the composer's success at making each prelude and each fugue absolutely different from the rest.