Denise Markonish Part Two

Projects for Mass MoCA

By: Denise Markonish and Charles Giuliano - Dec 15, 2011

Charles Giuliano It is poignant to recall Caroline Graboys and Jennifer Atkinson. Both successive directors of the Fuller Museum of Art died young of cancer. On my watch as a critic I often covered their exhibitions in particular the Triennials. Before Grayboys was Marilyn Hoffman who left to be the director of the Currier Gallery in Manchester, NH. One of her last shows focused on the 19th century Visionary artist, William Rimmer. Atkinson, who I profiled in my Perspective column for Art New England, produced shows for the Boston Expressionists Hyman Bloom and Henry Schwartz.

The Fuller was feisty and ambitious but somewhat hard to reach, not only in distance from Boston, but also tricky to navigate from the highway. You had to know your way through a shopping mall to find the back road to the museum. It was easy to get lost and frustrated. As I am sure it was for curators like yourself hoping that people would come to see the shows.

With all of the reaction to the Rose fiasco there was a similar event at the Fuller many years earlier. Faced with bankruptcy Grayboys opted to sell works from the collection to keep the doors open. At that time I was interviewing MFA director Alan Shestack. He gave me a hard line answer which I quoted in the piece. In essence he said that a museum with a 501C3, non profit status, facing a fiscal crisis should give its collection to another museum and close its doors rather than sell works for any purpose other than upgrading the collection. Because of the actions of Grayboys, which defied the ethical guidelines of the American Association of Museums (AAM), the institution exists and thrives today as the Fuller Craft Museum.

When I published the quote Shestack complained to my publisher/ editor, Carla Munsat, and threatened to sue. He demanded that I be fired. That happened several times at different publications including the Patriot Ledger. Actually, I was fired three times by Art New England, post Carla Munsat, and twice by Arts Media. Since founding Berkshire Fine Arts it is unlikely that I will sack myself. It is liberating for me and our contributors not to have to follow the whims of publishers, advertisers and editors. As editor I rarely say no to our many and diverse writers.

The Fuller Museum of Art got you up and running leading to the transitional gig at Artspace before coming to Mass MoCA four years ago.

Give us a thumbnail of your time at Mass MoCA. In general it is a vast museum which by proportion has a quite small but very vibrant staff. You and Susan Cross are the second generation of curators after chief curator, Laura Heon, who left for Site Santa Fe, and Nato Thompson, who now works for Creative Time in New York.

Your tenure started just after Mass MoCA had survived the Christoph Buchel standoff. It tied up the museum for a year and had a depressing impact on the staff. There was a lot of negative coverage in the media including the NY Times and Boston Globe. That was a tough time for the museum which has flourished since then.

Most significantly Jenny Holzer was the artist immediately after Buchel exhibiting in the vast space of Building Five. Working with an artist of her stature got the museum back on track. The widely acclaimed Sol LeWitt building opened after that. Last year, and again this year, there was the game changing Wilco Solid Sound Festival.

The impasse of the Buchel incident had a positive impact on Mass MoCA. Through the intensive soul searching involved in surviving the crisis the museum, which might not have survived, reemerged with greater focus and renewed commitment. It is an example of that which does not destroy us makes us strong.

You and Susan Cross have been key players in Chapter Two of Mass MoCA which is now early into its second decade of being open to the public. In many ways it is still very young as an institution and actively creating its own history and mythology.

What sense of that informed you when you joined the museum? How has that shaped and motivated your curatorial work? Even though located in an economically depressed rural region of Western Massachusetts the exhibitions, projects and events at Mass MoCA are targeted to a regional, national and international audience. Does all of that critical weight translate as a burden, or incentive and opportunity? Discuss your projects so far with Mass MoCA.

Denise Markonish Charles, yes it is good indeed that you can not fire yourself!

To touch briefly on your lead up to this question, I did hear about the early years at the Fuller, and think the issue of deaccessioning work is a very tricky one, perhaps a discussion for another time. But yes, the idea of “bailout” is a situation no museum wants to be in, and many times in the past the Fuller was on rocky ground. Due in part to location, as you mentioned, but also due to a mission that was often confused – contemporary art, historic New England, craft, etc. It was great for me since I could institute my own programming but I think that, over the years, identifying what the museum was continued to be a problem. In many ways the craft focus was a smart one, providing a niche for the institution.

I remember when I first heard about MASS MoCA, I was just finishing up grad school at Bard, and I thought... North Adams, why there??? As someone growing up close to Boston, there is this syndrome we have (I’m sure you recognize it), where we think that the state actually only stretches from say, Gloucester to Worcester! Misguided I know, but all too true. I never much considered the Berkshires. Then I came to MASS MoCA in 2000 for the Unnatural Science exhibition that Laura Heon curated (and the first place I would see Michael Oatman’s work). I don’t think I could close my eyes for a week after that, it was a complete state of wonder! The space, the art, the feeling of the whole place was unlike anything I had ever experience (and I still believe that today). I continued to come back here year after year in pilgrimage, thinking this an ideal institution for a project based curator. So then about seven years after my initial visit it was a “pinch myself moment” to be working here. I knew Nato (Thompson a former curator), got to know Joe (Thompson director of Mass MoCA) over the years and other folks like Richard Criddle (Mass MoCA’s preparator), so it was a perfect place to walk into. As you mentioned, it was a less than perfect time, in the midst of the Christoph Buchel exhibition, but I knew this place and knew that it would bounce back so that never deterred me.

As for the Berkshires, it is a place that surprised me with its cultural institutions, there is so much going on here that one never has time to even consider that they are at the edge of the state. We draw in a local and international audience as well. Another great perk is that in any where from 3-4 hours you can be in Boston, New York City or Montreal, yet when you want you can just be in the quiet of the mountains!

My first exhibition here was really a response to place but also to some ongoing curatorial interests of mine. Initially I told Joe I wanted to do a show called “The End is Here,” which was a bit too dark at the time. I ended up splitting that show in two, the first being Badlands: New Horizons in Landscape and the second being These Days: Elegies for Modern Times (Joe was on to me but supported what he calls my “dark dark dark” ways regardless). Badlands was the result of an ongoing fascination with the landscape, made even more prevalent in a place like North Adams, where the postindustrial lies right next to the pastoral. I had done projects before that touched on this investigation of the “natural” (Mark Dion’s works, the project I mentioned earlier in PA, and a show called Why Look at Animals? I did at Artspace).

I wanted to look at the artistic tradition of representing the landscape (mostly focused on the United States and things like the Hudson River School, The New Topographics and Earth Art) and provide a new chapter to that legacy, taking into account the beauty and decline of the world around us. These Days was the more poetic counterpoint to Badlands where I included 5 artists, asking them to respond to the form of the elegy. That show was really about mourning the state I think we as a country (and even globally) were finding ourselves in – always in conflict, the landscape disappearing all around us, and tired politics. It was an interesting show to do at the moment of the presidential elections where the word being thrown around was ‘hope.” My response to that was that hope is necessary but we can depend on it (dark yet again). In both shows I was also very conscious of choosing a range of artists from the well known (Robert Adams, Ed Ruscha and Sam Taylor Wood) to those less of an artistic household name (George Bolster, Micah Silver, Gregory Euclide, Vaughn Bell etc).

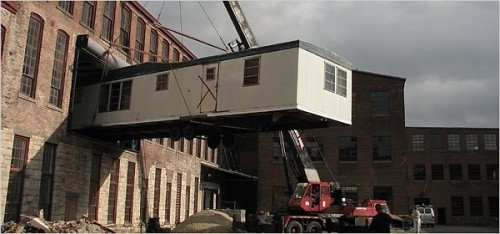

After that I got to take my first crack at Building 5, our large-scale, football field-sized space. And for that I chose to work with Inigo Manglano-Ovalle. I first saw Inigo’s work at the 2000 Whitney Biennial, but funny enough got a better introduction to it when a show of his traveled to the Rose in 2002. Inigo was the first artist I thought of for Building 5, knowing his masterful handling of scale and the in depth research his projects often take on. We ended up doing a project called Gravity is a force to be reckoned with, a 25x25-foot upside down house based on an un-built Mies van der Rohe structure from 1951. The piece played out a narrative drawn from such inspiration as Yevgeny Zamyatin’s 1921 novel We (a book that my uncle who taught at Brandeis incidentally wrote his PhD thesis on) and Sergei Eisenstien’s unmade film The Glass House. I am still inspired by the fact that Inigo could take a gallery of that scale, put something rather small in it and fill the whole space with the tension of the object.

After that I did a retrospective of works by Petah Coyne entitled Everything That Rises Must Converge (after the Flannery O’Connor story) and just opened an exhibition of all new work by Nari Ward. Nari’s show (on view until February 2012) takes a very interesting approach, aligning, I think I can honestly say, for the first time North Adams and Jamaica – looking at both as shifting sites of labor and memory. And of course there is lots coming up, Michael Oatman’s project all utopias fell, an airstream trailer/spaceship running off solar power is on view in the back area of the museum that we are currently developing. This space, just on the other side of the river in our back yard, will also contain an acre and a half garden project by Jane Philbrick and a sound installation in the former boiler house that ran the factory by Stephen Vitiello (who collaborated with local writer Paul Park on the content of the piece. You can see here literature usually has a recurring role in my thinking).

I think that brings me up to date! Many more projects on the burner of course...