Cubism for the Holidays

School of Paris Museum and Gallery Exhibitions

By: Charles Giuliano - Dec 17, 2014

Cubism: The Leonard A. Lauder Collection, at the Metropolitan Museum through February 16. Picasso and Jacqueline: The Evolution of Style runs through Jan. 10 at the Pace galleries, 32 East. 57th Street, Manhattan, and 534 West 25th Street, Chelsea; 212-421-3292, pacegallery.com. Picasso and the Camera runs through Jan. 3 at Gagosian Gallery, 522 West 21st Street, Chelsea; 212-741-1717, gagosian.com.

During his lifetime Paul Cezanne (1839–1906) was regarded as the least gifted of the impressionists and post impressionists. The writer/ critic, Emile Zola, was also from Aix. From the age of 13 they became friends with the artist following the writer to Paris.

When Zola wrote L’Oeuvre about a failed artist and social misfit he sent a signed copy of the book to his friend. Cezanne wrote a polite note of thanks after which they never spoke. The artist was convinced that the character was based on him.

Cezanne’s destruction of traditional perspective and reduction of observation to distortion and abstracted planes of color was widely regarded by peers and critics as evidence of a lack of skill.

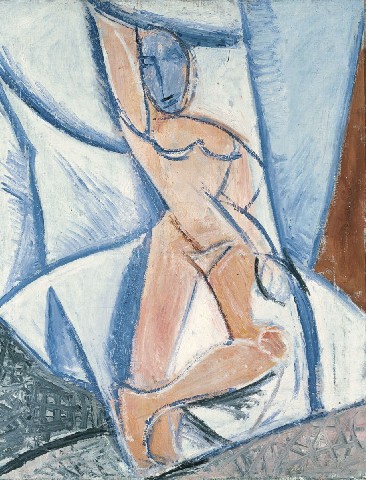

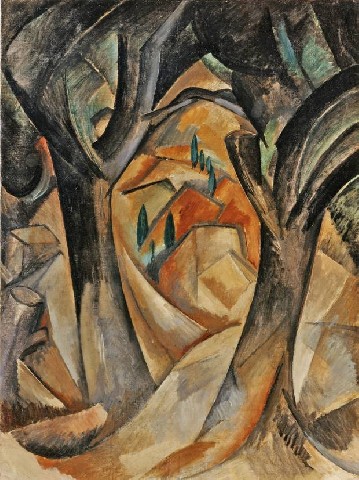

Two young artists in Paris, Georges Braque (13 May 1882 – 31 August 1963) and Pablo Picasso (25 October 1881 – 8 April 1973), visited the retrospective after Cezanne’s death in 1906 and viewed the work differently. Combined with Picasso’s interest in “primitive” art within a year, passing through the violently distorted “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,” they became partners in developing cubism.

For the next few years during the experiments of Analytical Cubism and its evolution to Synthetic Cubism they were inseparable partners. So much so that they called each other Wilbur and Oliver a reference to the Wright brothers as pioneers of aviation. They rightly consider Cubism as a cultural breakthrough on a par with man taking flight.

Scholars have noted that their attempt to create multiple vantage points in two dimensional images occurred precisely in the time frame of the theories of Albert Einstein. He published the works now referred to as Special Relativity in 1905 and General Relativity in 1916.

The artists took a rigid, disciplined almost scientific approach in their development of cubism. Only a trained eye can separate their work at key points. The artists delighted in that confusion. While inspiring each other they also influenced avant-garde artists in Paris and a broad swath from Mondrian in Holland to Malevich in Moscow, or the Futurists in Italy.

While having a pervasive impact on a multi national avant-garde, cubism remains less popular with collectors and museum visitors than impressionism, post impressionism or even the more lyrical and illustrative aspects of Picasso’s Blue, Rose and Classical periods. For the general public Cubism has always been a daunting and cerebral hard sell.

It would be a stretch to expect that the crowds flocking to the Met, as they did last summer at Tate Modern, have anything beyond a generic response and insight to what they are seeing. The same might be true of audiences listening to works by Igor Stravinsky after his 1913 “Rite of Spring” which caused riots in the Paris theatre when the ballet was first performed. Compared to his later works "Rite of Spring" is regarded as popular and ironically accessible.

The outbreak of World War I separated the collaborators. Braque enlisted while Picasso, a Spaniard and citizen of a neutral nation, did not. When it became untenable in Paris to be out of uniform Picasso visited Italy. There the artist/ poet/ filmmaker Jean Cocteau introduced him to Sergei Diaghilev and his Ballet Russes. In Rome Picasso met and later married the Russian dancer Olga Stepanovna Khokhlova. Eventually they separated but never divorced.

After the war Picasso designed sets for the ballet “Parade.” It is credited with bringing cubism to a wider audience through his inventive works for theatre. The text was provided by Cocteau. Set to music by Eric Satie the ballet premiered on Friday, May 18, 1917 at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris, with choreography by Léonide Massine and the orchestra conducted by Ernest Ansermet.

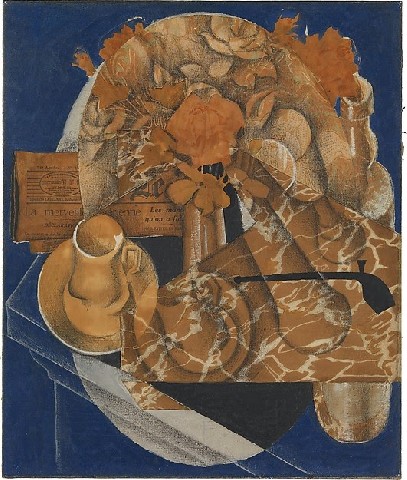

In addition to Henri Matisse: The Cutouts at MoMA during the current holiday season there are several exhibitions that focus on Picasso and his peers. The most astonishing of these is Cubism: The Leonard A. Lauder Collection which consists of 79 paintings – 34 by Pablo Picasso, 17 by Georges Braque, the remainder by Juan Gris (March 23, 1887 – May 11, 1927) and Fernand Léger (March 23, 1887 – May 11, 1927). This unprecedented gift from Lauder is on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through February 16.

The former home of the Whitney Museum on Madison Avenue is currently under renovation. It will be relaunched to display the Lauder collection as well as other works of modern and contemporary art owned by the Met.

In 1984, Lauder was given his pick of the estate of Douglas Cooper, the English art historian, a friend and patron of Picasso’s. He took out a $22 million loan to acquire key works. For ten years, 1950 to 1960, the art historian John Richardson lived with Cooper at Château de Castille in the vicinity of Avignon. Richardson had sustained access to Picasso. This resulted in an ongoing series of volumes comprising a definitive, insightful, readable and anecdotal biography of the Picasso.

As an authority on Picasso, with unique access to sources and archives, Richardson has curated several exhibitions for the Gagosian Gallery. The current one Picasso and the Camera, through Jan. 3, which also includes a number of paintings is intriguing but flawed. There have been mixed reviews for a project that fails to pull together what are at best family album snapshots and home movies rather than an in depth and innovative critical analysis of his work in the field of photography. This show mostly conveys that Picasso took pictures of his work as well as visitors, friends and lovers.

Based on this overblown and pretentious show that’s a fair but not accurate conclusion. At the Picasso Museum in Paris some years ago I viewed a more diverse and interesting exhibition that revealed that he did indeed experiment with the medium however tentatively.

The other exhibition in this holiday orgy of the ever popular School of Paris is Picasso and Jacqueline: The Evolution of Style which runs through Jan. 10 at the Pace galleries.

If one follows the thesis of John Berger’s insightful “The Success and Failure of Picasso” during the late period with the ambitious and sheltering Jacquline it seems the artist was cranking out Picassos. The Guggenheim devoted an exhibition to the late period but most of those potboilers are facile parodies of earlier and greater works.

Because by then Olga had died he lacked an excuse not to make Jacqueline his second wife. That, combined with his declining health, gave her enormous powers. Like Alma Mahler she mostly played the role of wife/ nurse to an old man.

Jacqueline isolated him from friends, artists and family. Like the Catalan poet Jaime Sabartes years before she served as the gate keeper for those seeking access to the master. These were key factors in the Berger analysis of his creative decline. It is essential to the work that artists remain in critical dialogue with other artists and developments in the field.

As his wife Jacqueline also exerted considerable control over the artist's estate. In the role of muse/ goddess she was less significant than the inspiration of Fernande Olivier, Marie Therese Walter, Dora Maar the toughest and most accomplished of his women, Sarah Murphy or Françoise Gilot. Few if any great works were inspired by Jacqueline. By comparison Maar was in the studio daily and took documentary photographs of his masterpiece "Guernica."

Whom the gods love die young. Picasso, however, went way past his aesthetic deadline.

The raging hormones and genius of the early Picasso works in the Lauder collection are, however, energizing, fascinating and utterly galvanic.

This exhibition entices us to compare and contrast.

There is the conundrum of separating responses to paintings by Picasso and Braque. Without checking labels one might easily be fooled. It has become a trope of art history exams to project side-by -side works by the artists and ask students to write essays on their similarities and differences.

An exception however was a work clearly from the series of studies that resulted in "Les Demoiselles d’Avignon." Scholars, including an absorbing book by Wayne Anderson that I discussed with him at length, note the many changes he went through in developing the seminal work. The number of sailors/ johns was reduced. One scholar argued that a slice of watermelon represented the “splayed vagina” of a prostitute. Wayne felt that it was a part of the ambiance of a brothel where men went to eat and drink as well as have sex.

Some accept the work as the first cubist painting while others state that it was proto cubist leading to what would follow. The artist kept the painting displaying it to artists and those who visited his studio. Arguably, it is the singular work of 20th century art. So anything that references it, like the Lauder study, is of enormous value and significance.

When Braque returned from the war they interacted but never worked together. After that Picasso was never again so pure and focused while the work of Braque lost its grip and intensity.

It is interesting that Lauder included Juan Gris and Fernand Leger in his collection.

The works by Gris are always precise and superb technically. Although a fellow Spaniard the work of Gris lacks that passion, blood, machismo and duende that we associate with Picasso.

The paintings by Leger are far more interesting, original and inventive. In addition to the formalism of cubism he was passionate about leftist politics. That gave him an approach to conveying heroic aspects of workers conveyed in machine like forms. He was fascinated by the mechanics of emerging technologies of the early 2Oth century which similarly absorbed the Futurists. They were inspired by a mechanical age of fast cars, airplanes and locomotives. In the case of the futurists add to that the arts of war.

Leger is on the short list of artists initially difficult to understand but ever more intriguing the more we are exposed to the work. Most significantly he veered far enough away from Picasso and Braque not to become what Richardson has dubbed The Salon Cubists (Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Robert Delaunay, Henri Le Fauconnier).

While cubism created new paradigms for pictorial space there is more to it than a formalist analysis. The Lauder exhibition combined with a visit to MoMA and "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon" are a good beginning to ask why.