Dishwasher Dialogues: Drink Overture of Days

Driving Backwards in Paris

By: Greg Light and Rafael Mahdavi - Dec 27, 2025

Greg: If our encounters with authority were generally blessed, there were times when the absence of authority was just plain lucky. Especially when substances were involved.

Rafael: We were young, our bodies could take it, the wine, the beer, the cocaine, the weed, the poppers (isoamyl nitrate). Looking back, it was pretty insane, and yet our creativity, our rage de vivre continued undiminished. Yeah, I know we have to mention sex at Chez Haynes, and yes, there was quite a lot of it; some would call it fast and loose, others warm and sentimental, generous and exhilarating, faithful and jealous. There were broken hearts and tears too. And we drank too much probably, we let go and laughed our heads off, and there were times of leaden love-sadness.

Greg: That rings true to me. During these most impulsive years, before growing older came along, we essentially glided through an era of sexual inconsequence. Nothing catastrophic happened to defy our youthful defiance. The sexual revolution and the pill were history. The fear of pregnancy was already a decade in the past. The fear of AIDS was a decade in the future and antibiotic resistant bacteria was still science fiction. The culture of alcohol was synonymous with the good life—public health meekly suggesting we limit our consumption to a different level of alcoholism. Drink was the great overture of the day.

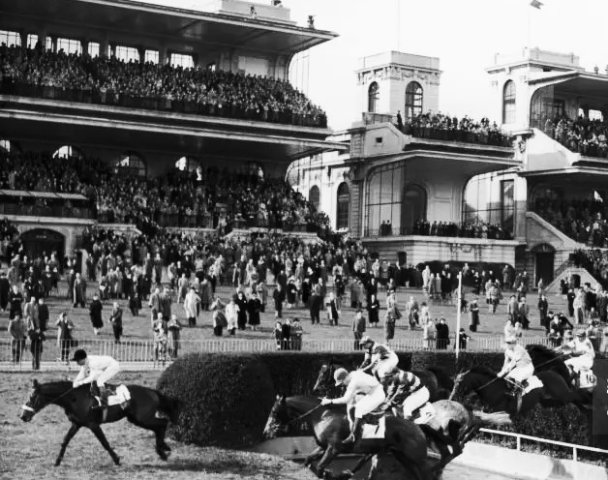

Rafael: The staff could drink as much as they wanted, as long as they didn’t wobble too much on their feet when they served the clients. Yes, we all drank, and on busy nights, as the hours dragged on, the waitresses, bless them all, kept going with tequila sunrises and whisky sours. Don would come out of the kitchen and order a Jack Daniels, Blackjack as he called it. And as I already mentioned, there was cocaine, too, once in a while. Great stuff, made you fast like a dancer, daring, self-confident. And Leroy was generous. One Monday evening Leroy gave everyone on the staff a bottle of Mouton Rothschild. He had won big at the Longchamp racetrack and was feeling even more generous than usual.

Around that time my grandmother died and left me a thousand dollars; and I bought the second-hand VW. It was a change in my life. A big change. No more carte orange, remember? And parking was no problem in those days in Paris. Nobody ever paid their parking tickets.

Greg: The one time I remember driving in Paris, I got tangled up in the giant roundabout circling the Arc de Triomphe on Place Charles de Gaulle. Eight lanes at a minimum, but back then there were no lane markings to indicate one from the other. I entered, got forced toward the center and circled around and around for half an hour before I could find my way out the other side. Never again. And I swear I was substance free.

Rafael: Sometimes we mixed our substances. My uncle worked at the Iranian embassy in Paris. Every so often he’d give me a two-kilo tin of Persian caviar. One evening we found ourselves in my one-room apartment with some of the Chez Haynes staff.

Greg: 183 Rue Saint Martin. I still have good memories of that street and that room. And many, many more that lost their way on route to my consciousness.

Rafael: The conversations at such gatherings were always interesting, unexpected, staccato. The topics ranged far and wide, and with a little help from the wine and the weed we touched upon films, photography, dance, theatre, painting, and more. My place was small, maybe ten square meters, and we sat on the floor and on the mattress. We also brought two bottles of vodka and a few lemons from Chez Haynes. I opened the tin of caviar and with a soup spoon scooped out some of that black goo, squeezed lemon juice on it, took a swig of the vodka and then a ‘toke’ from the joint. I passed the caviar tin and the spoon to one of the girls. And it went around. Then somebody had the bright idea to hand out some poppers, which as you may remember makes your heart rate jump to 200 beats a minute––for a few minutes, like the Apollo rocket right there in your chest. And out of the blue, your cousin who was also there took a popper and a few seconds later announced she suffered from a heart condition. Panic stations! I suggested she drink a glass of water, which she did. The rush passed in a few seconds and your cousin and the rest of us were relieved, and that’s putting it very mildly, that she hadn’t died.

Greg: Memories of that evening have returned! Thank you. Mainly, I think, because of the caviar. And the poppers. And the heart episode. But, for the life of me I cannot think of which of my cousins might have been there. Maybe Harry’s cousin. She seemed to attract unwanted events. Bentley was also there. All of us devouring our way through spoonful after spoonful of this delicious and expensive egg dish that would have cost a fortune in the best Parisian restaurants.

Rafael: And one night, a few weeks later, after closing at Chez Haynes, I drove you and Laura and Scott back to their apartment on Réaumur where we smoked a joint and proceeded to get very drunk. I have forgotten if we had a reason to get soused, probably not.

Greg: It was that night I remember as the ‘tequila night’. We went to Laura and her boyfriend Scott’s apartment. They were near the end of their relationship, and I remember him being a little morose that night. He didn’t join in. In retrospect maybe that was a good idea. I don’t remember drinking anything but tequila, and smoking lots of weed. Again, we brought the bottle from Chez Haynes. Leroy was secretly killing us with his generosity.

Rafael: The point is that at three or four in the morning we decided to call it a night. I wanted to drive you home all the way to the Porte d’Orléans. But I knew damn well there was no way I could drive across Paris, from the second arrondissement to your place. I pulled out of the parking space on Réaumur, and for some reason, I began to drive backward the wrong way down Reaumur, a one-way street. It must have been a good three hundred meters, right on past Sebastopol. I remember backing up by looking in the side mirrors. A miracle we didn’t die, and another miracle was that there were no cops around and very few cars.

Greg: After that slick backward driving move, I have a strong and distinct memory of us driving forward along the Rue de Rivoli, its arches in the mist and rain and lights sliding by, and you suddenly shouting out ‘look, I’m driving. I’m driving,’ with this amazed look on your face. Like, you were watching from afar and just became aware of this marvelous feat of muscle memory. (‘Look, no hands.’) Which I guess it was. Until that moment, not for a second had I thought our late-night journey was out of the ordinary. Then I began to wonder. What the hell are we doing? Somehow you parked. Thankfully, driving is mostly an unconscious activity; and your brain decided not to let your mind intervene.

Rafael: You passed out on the floor of the apartment, and I fell asleep on the bed.

Greg: On a floor you ‘pass out’. On a bed you ‘fall asleep’. The outcome was the same: oblivion by alcohol.

Rafael: At eight in the morning, the phone rang, and I answered it saying in as cheery a voice as I could muster, ‘Chez Haynes Restaurant, bonsoir, how can I help you?’

Greg: You may have thought you were cheery and pitch perfect, but it was force of habit that got you through the greeting. I don’t know who was on the other end and I was in no condition to care, but once habit deserted you, it took you some time to figure out where you were, who you were and what planet the caller was from.

Rafael: All this happened a long time ago, and we could handle the drinking.

Greg: Really? Could we?

Rafael: Thinking back, I admit we were quite often drunk, and the odd thing is I can’t remember the hangovers. Now at 75 I have an occasional drink, say every six months, or so, and never get really drunk, but now the morning hangovers are tremendous, like Mack semis careening around in my skull. Just awful. Takes me a day to recuperate. How did we do it? We weren’t doing any exercise; we weren’t physically especially fit. And yet I never had a hangover in the Chez Haynes days.

Greg: The hangovers were there. We were just able to shake them off more easily. They did not wreck the next day as they do now. And they did not stop us from doing the same thing again the next night. I do remember learning to drink a lot of water and taking two aspirins before falling asleep. It worked well when I remembered to do it. It rarely (meaning never) worked (meaning happened) just before ‘passing out’ on a floor.

Rafael: At the time I did not notice how many adults around me were heavy drinkers. That was because I never hung out with adults, especially in the evenings. Was I an adult? Yes and no. More no than yes.

Greg: I don’t think pleading we were not adults at the time will justify the stupidity to which these memories confess. Even relying on youth as an excuse is a stretch. However, it was a place and time when the epitome of public health was limiting alcohol consumption to one bottle of wine a day. If we sometimes exchanged that wine for tequila, surely, we were still within the Parisian bounds of ‘almost acceptable’.

Rafael: I knew that Leroy was a total alcoholic because I counted the bottles he drank from the bar. I kept drinking until I was in my late fifties. Did I become an alcoholic? Probably. I was drinking two bottles of wine by myself as soon as I got home from work in the evening. This of course was many years after Chez Haynes. I looked forward to it, the drink, I mean. I always remembered how much wine there was in the icebox, and if there was less than a full bottle, I would make sure to buy some on the way home, even if it meant going all the way to Nation where there was an alimentation générale open late. Did I look forward to that first drink? Of course, you have no idea.

Greg: I think I have an idea. But maybe just an idea. Paris was the apex of my drinking. Not that I refrained from over-indulgence later on, just terminated its perpetual motion.

Rafael: After the first gulp I’d wait for the knock-knock, ‘hello I’m here’. But the first gulp was never enough. I needed two or three to feel that first buzz which told me everything was all right. With scotch it was easier, the knock-knock came faster, one gulp usually got me started. And no, I didn’t give a shit if the scotch or the wine was good or bad, all I cared about was the alcohol content. How can you not drink once you’ve known that warm, beautiful feeling telling you you’re all right with the world? I have an iron will, and I finally stopped hitting the sauce. I have an iron will because as the biologist Dawkins says, I won the genetic lottery. I didn’t will my iron will. You don’t will to be lazy or dyslexic or have a flawed digestive system or smelly feet or a sense of humor.

Greg: I think we are on the edge of our decades long debate about free will here. In saying you didn’t ‘will your iron will’, I assume you are saying self-discipline is just genetics. Is youthful stupidity just genetics? Do we have an excuse after all? Even though I continued to work in bars in London for several more years, I too curtailed the heavy drinking. I attribute it to age and chance in partner and circumstance as much as any genetic mutation. But maybe that’s splitting hairs.

Rafael: I still miss alcohol today, fifteen years later. I quit in 2006. And when I am invited out to dinner, it is still difficult not to drink. I sometimes fall off the wagon. I see now that most parties are just an excuse for getting soused with friends. I stopped smoking when I stopped the booze. I don’t miss smoking. I used to love smoking and drinking when I did the International Herald Tribune crossword puzzle. I stopped doing the crossword puzzle. Stopped the weed too when I had children. This has been a bit of a digression, but we said we’d keep this dialogue about those years honest, open, even if it means being a little gushy at moments.

Greg: Gushy works. Honesty is sometimes a little more troubling. At some point near the end of my stay in Paris, I think the drinking may have caught up with me. I was only 29. I don’t know if you remember but I came down with a wicked case of tonsillitis. I knew the symptoms well, as I had been prone to it as a kid, and it became a regular visitor. Fortunately, antibiotics always worked brilliantly. I remember Laura suggesting a local GP near the Place d’Alésia. A young doctor, just setting up his practice. I told him that I just needed antibiotics, but he insisted on a full work up including an ECG. I am pretty sure I was very close to being his first client, certainly his first ECG patient. He pulled out the machine, still gleaming and wrapped in plastic. It was all cords and plugs and sensors which he appeared to fumble with. It didn’t help that he looked like Woody Allen at his most ungainly. A half hour into hooking up the machine and sticking and unsticking nodes to my chest, I thought he was going to electrocute me. He finally got it set up and the reading began ticking out. Then he started to look alarmed. Then I started to look alarmed. My heartbeat was all over the place although I did not feel anything different. That’s when he referred me to St. Joseph’s hospital. It was very close, maybe a ten-minute walk at most, but he insisted I take a taxi. Which scared me.

Rafael: A taxi, eh? Spending big time for the ticker is understandable.

Greg: I pictured myself dropping dead on the sidewalk, which may have been what he pictured as well. I was immediately admitted and hooked up with all kinds of tests which delayed any antibiotics. For the first few days I felt increasingly ill. When you and the Chez Haynes people came by to see me, the look of sympathetic dread on your faces was not comforting. A week later, I was released. After finally getting some antibiotics, I was feeling great, but my heartbeat was still lop-sided. It was diagnosed as lone atrial fibrillation, for which the treatment was rat poison. Warfarin. And a second drug, the side effect of which meant keeping fully out of the sun. When I asked them what caused it, they were unsure—hence the ‘lone’ designation. They said it could have been something to do with the tonsillitis—I knew the irregularity was not there a week earlier because I performed Black to Black at the American Center on Boulevard Raspail and, to help me focus in the wings before I went on, I would close my eyes and count my pulse.

Rafael: I never knew you even focused like this. Is that what you always did before you went on stage?

Greg: Yes, that was my way of relieving my nerves—mainly for my one-man shows. Anyway, the cardiologist added nonchalantly as I was dressing to leave, that the condition could be due to heavy drinking. That might bring it on. He was not sure. I was not happy. I had, after all, been rigorously following their public health guidelines and drinking a bottle of wine a day. I still have the condition over forty years later. Day after day. it continues to relentlessly pound out its random beat. I am still unaware of it, but I am now on a cocktail of older-man substances to give my heart a fighting chance. So far so good. I never fully stopped drinking, but I did become a little more health conscious—maybe that was a parting gift from Paris. There, a little extra gushy for you.

Rafael: Anyway, we can always edit out. That was also one of the rules of this dialogue.

Greg: We haven’t edited out anything yet. But we have not remembered everything yet either.

Rafael: As parting gifts go, it’s pretty bad, worse than the proverbial gold watch from GM, that’s General Motors. I had worked the night shift for four months at the GM plant in Flint, Michigan, before I graduated from art school in 1968. Absolutely brutal. But not as bad as your heart going wonky on you.

Greg: You were a UAW man, also? So was I. For three months. I worked the night shift in a Chrysler factory the summer before I left for Paris. So, are we just union guys at heart?

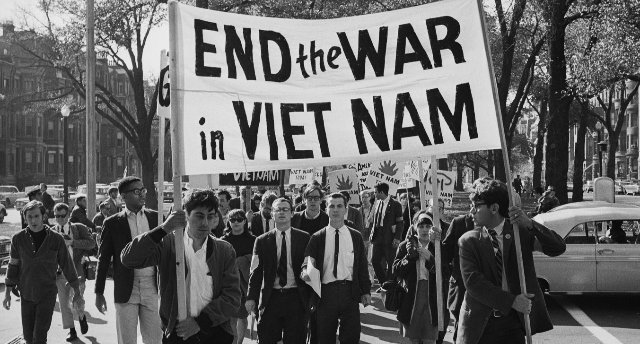

Rafael: I’ve forgotten whether I was union or not. But I do remember the atmosphere was tense. My stint at GM was in 1968. America was polarized. The Vietnam War, the civil rights movement. Some of the workers packed guns at work on the assembly line. Others were stoned all the time. The job paid well. But back to your heart. It makes sense in a French way; the Parisian culture vultures always favor the artistic and creative dead.

Greg: I know you are talking about my death by heart attack. But I am not sure what to make of that?

Rafael: Okay. I won’t go on a rant here against the critics, the self-appointed midwives of culture. Critics of all stripes.

Greg: I am sure critics have no interest in my heart. Beating or not.

Rafael: While I’m on the subject of this dialogue, let me say that I don’t believe in the soul.

Greg: That’s harsh. Some critics have souls. What do the young say today. Laugh out loud?

Rafael: Selling our Souls in Paris. That would have been a good title for this book.

Greg: I am not so keen. In the first place, it’s a hard sell if it doesn’t exist. And secondly, what else would the soul exist for if not to be sold. Every time we open our mouths, put brush to canvas, pen to paper, even a smile or a wink across a crowded restaurant, we are selling our souls.

Rafael: Most people come to Paris to find themselves. We often lost ourselves and it was fine. And what you say about selling one’s soul sounds right.

Greg: Thanks. Maybe it’s just the word for me.

Rafael: My version of the soul has to do with the dreams and hopes that I was carrying around. Selling them was good, it made room for more dreams and hopes, unclogging the metaphysical plumbing.

Greg: Thank you for not saying ‘religious’ plumbing. I can just about accept the idea that selling one’s soul is little more than aesthetic foible and compromise, and on occasion, willing submission to one or more of the seven sins. But I am happy to accept your connection to dreams.

Rafael: Leroy hired dreamers, artists, poets, writers.

Greg: Leroy. Now, there was an amazing soul.