Artist Helen Frankenthaler at 83

Her Paint and Reputation Spread Thin

By: Charles Giuliano - Dec 28, 2011

The position of Helen Frankenthaler in the hierarchy of Post War American art rests precariously on a single remarkable work “Mountains and Sea” (1952, collection of the National Gallery of Art).

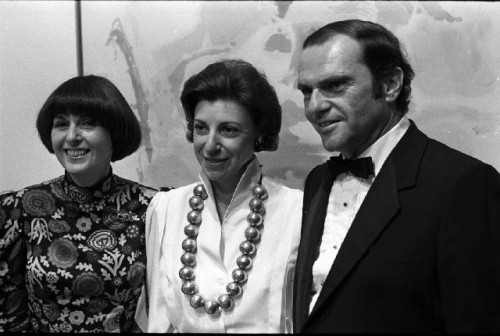

In May, 1981 I spent an afternoon with her prior to the opening of Frankenthaler: The 1950s at the Rose Art Museum. By then she was past her prime. The exhibition, organized by Carl Belz, was an in depth view of the decade when her work held a key position in the American avant-garde. The annual show, timed for commencement, was sponsored by Lois and Hank Foster.

Oil paint thinned into watercolor like washes was allowed to bleed into or stain unprimed canvas. Upon returning from a visit to Nova Scotia she abstractly evoked the experience with an innovative technique. It expanded upon the drip and stain radical methods of the abstract expressionist painter Jackson Pollock.

From a technical and conservation viewpoint oil and turpentine applied to unprimed canvas is anathema. Raw canvas must be prepared with a layer of gesso. This isolates the material from its support without which the paint and medium prove to be corrosive and may weaken and rot the canvas.

The development of water soluble paint with a plastic or acrylic binder allowed for non destructive stain paintings.

Frankenthaler, who had been in failing health for some time, died in Darien, Connecticut on December 27. She was born in New York City on December 12, 1928 the daughter of Alfred Frankenthaler a New York State Supreme Court Judge.

Her German born mother Martha (Lowenstein) emigrated from Germany as an infant.

She and her sisters Marjorie and Gloria, both deceased, were raised in a wealthy, cultured family. At the upscale Dalton School she studied with the Mexican artist Rufino Tamayo (1899-1991). At Bennington College an exclusive, expensive, and progressive institution for women she studied with the now largely forgotten abstract painter Paul Feeley (1910-1966).

From Bennington she returned to New York. As a young artist she had a five year relationship with Clement Greenberg (1909-1994) the most influential critic of his generation. Greenberg was a power broker in the New York Art World. His theories and views had the ability to make or break the careers of artists. His only real rival during this era was Harold Rosenberg (1906-1978).

At the height of his career Greenberg’s formalism dominated critical thinking. It had a broad reach into the acquisitions of curators at major museums. When traveling around America one found the identical elite group of artists he favored in the contemporary collections of museums.

This included the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston where the first curator of contemporary art, appointed in 1971, was Kenworth Moffett a Harvard educated disciple of Greenbergian formalism. Frankenthaler was among the artists whom Moffett collected in depth for the museum.

With the artists he favored Greenberg was a constant presence and influence in their studios. He was known for going beyond the limits of a “crit.” While Greenberg dabbled in painting, largely generic figures and landscapes, he was an ersatz creator through the artists he advised.

Three of them- Morris Louis (1912-1962), Kenneth Noland (1924-2010) and Paul Reed (Born 1919)- resided in Washington, D.C. During visits to New York Clem would take them around to galleries and studios.

It is said that Frankenthaler was not present when Greenberg took Noland and Louis to her studio. They viewed her breakthrough painting “Mountains and Sea.” That launched them into a dramatic change of direction.

When the Lannan Foundation was located in West Palm Beach it was possible to view a transitional body of work by Louis that spanned the before and after of that encounter with “Mountains and Sea.” Patrick Lannan (1905-1983) was known for striking deals to buy the content of an artist’s studio. In that regard the collection allowed for seeing seminal periods in singular depth.

Based on this evidence there is the compelling notion that, without the influence of Greenberg and Frankenthaler, Louis would have remained an undistinguished high school art teacher.

In 1964 Greenberg organized an exhibition of this emerging generation of artists under the escutcheon of Post-Painterly Abstraction. The style is more commonly known as Color Field and occasionally Stain Painting.

Through her relationship with Greenberg she had access to the inner circle of the New York School and the abstract expressionists. Like many of her generation she studied with Hans Hofmann (1880-1966) and absorbed the radical work of Jackson Pollock (1912-1956) when it was shown in 1950 at the Betty Parson’s Gallery. His “Autumn Rhythm” (Metropolitan Museum of Art) was particularly important as a jumping off point for the innovations that started with “Mountains and Sea.” That Parsons show also included “Number 30, 1950” “Number One, 1950” and “Lavender Mist.”

These are among Pollock’s greatest works. In response Frankenthaler stated “It was all there. I wanted to live in this land. I had to live there and master the language.”

When the relationship with Greenberg ended she married the abstract expressionist Robert Motherwell (1915-1991) in 1958. They divorced in 1978. As individuals from wealthy and privileged families they were a power couple in New York society that fixated on the high end of the art world. They traveled broadly and entertained lavishly. While in the second tier among the artists of the New York School Motherwell was its greatest thinker. His books, particularly on the Dada movement, are still widely read.

Arguably, it was the Midas touch and upscale lifestyle of Motherwell and Frankenthaler that denied them the agita that was essential grist for the artists of their generation. It is unlikely that there will be best selling biographies, films, and plays about their bourgeois lives and work.

While they were smart, arguably brilliant, they were unable to sustain the intensity of their innovations. Although they are identified with abstract expressionism in their practice the work devolved into mannerism noted for a facile, decorative artificiality. The “drippy” edges of Motherwell, for example, particularly in the large canvases, were preplanned and executed precisely with a small brush. He simulated, in a deliberate, cerebral manner, the spontaneity and ferocious attack that was notable in the work of Pollock, and de Kooning.

As the work of Frakenthaler progressed through the decades it was notable for a prettiness of color and decorative pastiche. Compare her fields and stains, for example, to those of Mark Rothko. His were produced in response to inner demons as was brilliantly conveyed in the play “Red.”

Let us not, however, cast judgement. We all have the distinct choice to sell our souls to the devil to make compelling art or take a step back and live a comfortable life. You have to suffer to sing the blues. There is no evidence of that in the work of Frankenthaler.

With the emergence of pluralism in the 1970s and 1980s the hegemony of Greenbergian formalism was assaulted. Among emerging artists, curators and critics there was an Oedipal critical assassination. The dominance of formalism was shoved aside and assigned a lacuna in the scrap heap of taste and style.

In a December 28, 2011 obituary in the Wall Street Journal Eric Gibson wrote that "...Time had not been kind to these icons of 1960s and '70s art. They were beautiful, to be sure, yet suddenly they seemed plagued by a decorative emptiness. Overnight, it seemed, heroic American abstraction had devolved to nothing more than college-dorm eye candy. Greenberg was a brilliant critic, but his view that the proper subject of art was art itself was too narrow and insubstantial a foundation on which to erect an enduring vision.

"Frankenthaler herself sailed dangerously close to this aesthetic reef. This was particularly true in the '60s, when paintings consisting of a few simple forms and a heavy use of primary colors created a kind of Marimekko effect—works that made attractive backdrops but didn't compel a long gaze."

While the work of Frankenthaler continued to be celebrated with museum exhibitions and acquisitions it was largely ignored or ridiculed by critics. For Frankenthaler living well may have been the best revenge.

Surrounded by her work at the Rose Art Museum in 1981 I asked what it felt like to see the painting together some 30 years after they were created. “I feel very proud of it and somewhat amazed” she said. “Of course I am very familiar with the work but this is a refreshing experience for me and it makes me see it again in a beautiful way. And this work is a part of a whole long thing that has been going on. It shows where I’ve been. Where I might be and where I might be going. I see the seeds of things that have been developing.”

Significantly, she opted not to include “Mountains and Sea” in the survey of her work from the 1950s. She stated that she did not want it to distract from looking at the range and impact of the other works. Taken together they did convey a fresh, sanguine energy and originality.

Dialogues with artists can be cumbersome. There is so much that a critic wants to know particularly about influences and the impact of the work on other artists. How did Pollock, for example, jump start her evolution? We asked what she learned from Greenberg and Motherwell. What did she have to say about how viewing “Mountains and Sea” impacted the development of Louis and Noland?

She listened to the questions and then answered imperiously.

“One thing leads to another” she responded. “You use what you have to use. What you’re asking is how does an artist really develop an aesthetic? That’s impossible to answer other than what makes a specific painting work and why is it beautiful. Any real message comes from looking at what one has done and continuing to grow and develop.”

Other than bumping into her work at upscale galleries during annual visits to Palm Beach, with impunity, that interaction at the Rose was the last time I critically engaged the work. Until today.