Chaos and Classicism at the Guggenheim

Landmark Exhibition Closes January 9

By: Charles Giuliano - Dec 30, 2010

The provocative and enigmatic exhibition Chaos and Classicism: Art in France, Italy, and Germany, 1918-1936 closes at the Guggenheim Museum on January 9, 2011.

While most blockbuster exhibitions focus on the household names this exhibition was notable for a daunting mix of a few works by modernist masters as well as an intriguing number of works by artists who, while dominant and successful during their era, have for complex and intriguing reasons, been relegated to the dust bin of memory.

The exhibition presents works by established masters of the period, including Georges Braque, Carlo Carrà, Giorgio de Chirico, Otto Dix, Fernand Léger, Aristide Maillol, Henri Matisse, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Pablo Picasso, Gio (Giovanni) Ponti, Emile-Jacques Ruhlmann, and August Sander, as well as works by artists lesser known outside of their home countries, such as Julius Bissier, Felice Casorati, Achille Funi, Marcel Gromaire, Auguste Herbin, Anton Hiller, Heinrich Hoerle, Ubaldo Oppi, and Milly Steger. Many works have never before been shown in the United States.

This is an experience that profoundly challenges, morphs and subverts the conventional interpretations of modernism during the first third of the 20th century. In many examples this proved to be an unsettling encounter evoking guilty pleasures.

It begged the perennial issue of the difference between good art serving a bad cause or bad/mediocre art celebrating a noble cause. Many of the works in this project clash at the matrix of social and polemical extremes.

In art as in war to the victors go the spoils. With hindsight the authors of art history texts, and curators of museums tend to celebrate the avant-garde, the underdogs, while slighting or relegating to contempt and neglect the academic, conservative, and mainstream populist art of the masters and their political overlords.

It is difficult to rail against this process that now considers the German Expressionists, for example, as the enduring masters of their time, while the Fascist artists who repressed the avant-garde, are neglected and rarely seen.

The issue of art under fascism and Marxism, which flourished with official sanction between the wars, is a daunting quagmire for accurate critical thinking. In the scope of this exhibition it is unfortunate that the organizers opted not to include Soviet art.

Much of the art of the Third Reich was confiscated by the U.S. military and deported for safe keeping, never again to see the light of day, in state of the art storage facilities. Images of Hitler, of which there were many, as well as works by the Fuehrer, are considered to be particularly verboten.

These images may be seen in books and glimpsed occasionally in exhibitions such as that organized by New York University Professor of Modern Art Kenneth E. Silver, a renowned authority on European art between the wars, assisted by Helen Hsu, Assistant Curator, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, with Vivien Greene, Curator of 19th- and Early-20th- Century Art, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, as curatorial adviser.

As we rambled along the sloping ramps of the Frank Lloyd Wright designed museum the spiral of art evoked a vortex of confusion and wonder. Unless you paused to read the labels it was often challenging and confusing to separate the good art from bad work.

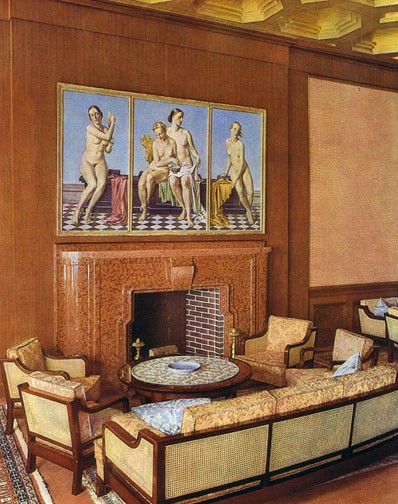

I found myself pausing in admiration of a triptych of nude blondes depicting the Four Elements by Adolf Ziegler. There was a gentle sense of naturalism in color and meticulous academic rendering. Surely this was a gentle and seemingly benign celebration of feminine form and beauty. How could one not admire such a seductive, charming, and classical painting.

As post modernism has informed us, however, art is not innocent. A more careful view and consideration of the painting reveals that it is a signifier of the Nazi mantra of the superiority of the Aryan race. The four lovely maidens were indeed pinups of the breeding stock of the Third Reich.

It was shocking to learn that this particular work hung over the mantle piece of Hitler’s apartment. Ziegler was a zealot who set the aesthetic standards for the regime and was an instrumental force behind the notorious exhibition Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) which opened in Munich on the 19th July, 1937.

Similarly in the Annex gallery in the top of the museum I was transfixed before gigantic works, studies for murals, by the Italian fascist, Mario Sironi. This is an artist whom I had never heard of. But the scale, freshness of attack, and proto expressionist energy of the works evoked comparisons to paintings by Julian Schnabel. There may indeed be some irony in conflating Schnabel to fascism. Sironi is presented here creating enormous monuments to Mussolini mounted like a condottiero by Donatello.

There are fascinating sculptures of Il Duce. There is a very strong and menacing, life size, bronze bust by Adolfo Wildt. As well as, a continuing, swirling portrait in the futurist style by R.A. Bertelli. As a modernist sculpture it is compelling. It is sobering to realize we are admiring an inventive portrait of a fascist dictator.

Ironically the work endorsed by Mussolini is far more interesting, even avant-garde, than the vulgarian taste of his comrade Hitler. It is a conundrum that the progressive Futurists seemingly embraced fascism. Just as confounding is the fact that the German Expressionist, Emil Nolde, was a member of the Nazi party.

This opens up a grey area in cultural studies. Consider, for example, the Dreyfus affair in France which divided the nation, including artists, into pro and anti Dreyfus factions. It is chilling to learn which of the impressionists, Renoir for example, were anti Semitic.

Volumes have been written about which French artists and entertainers during Nazi occupation and the Vichy government were active or passive collaborators. Not every artist joined the resistance. Paris remained the City of Lights. Picasso’s studio was among the tourist attractions of the occupiers.

Of course we have the perhaps apocryphal anecdote of a German officer who, during a studio visit, pointed to Guernica and asked “Who painted that?” The famous reply was “You did.”

The few works by Picasso in this exhibition are from his neo classical period. The most famous and familiar example from the Met is “Woman in White.” It slides easily into this survey and surely beefs up the box office appeal of the show. But it begs the question of why after an intense period of pushing the limits of cubism Picasso slid back into this more accessible, and perhaps, more saleable style. It is often suggested the he was attempting to please the conservative taste of his Russian wife, the ballerina, Olga Kaklova.

One of the delights of this exhibition was a portrait of Olga from a private collection. It is a poised and stylized rendering, reductive and linear compared to the more descriptive, realist, familiar portrait of Olga with a mantilla. In this less known example the husband seems less intent in portraying her than rendering Olga as a modernist deity.

The exhibition succeeds in conveying the extent of the influence of classicism during the era between the end of World War I and the beginning of World War II. It is the shadow of war and the Holocaust that darkens the sublime serenity of many of these images. The works illustrate the thesis of why political dogma held hostage the Apollonian ideal as the instrument of its hateful propaganda.

In apparent counterpoint to the prevailing classicism one of the side galleries presents the suite of prints by Otto Dix that convey his experiences as a combatant during WWI. Similarly discordant was a display of the photographs by August Sander. While they define the archetypes of Germany they are hardly classical in intent or inspiration.

There is no more compelling example of this than the magnificent, malicious films of Leni Riefenstahl. She was by far the greatest artist employed by the Reich. There is a part of a gallery dedicated to screening the prologue of her masterpiece “Olympia.” With artful shadows and dramatic cinematography she conflates plaster casts of Greek sculptures that evoke nude Aryan athletes. A shot of Myron’s Discobolus morphs into the torsion of man hurling the discus.

Recently, I had a difficult time conveying to a Jewish artist why Riefenstahl deserves to be regarded as one of the greatest artists of the 20th century. It is a conundrum that after the war she was not put on trial as a criminal. She claimed that although she worked for Hitler she was never a member of the Nazi party.

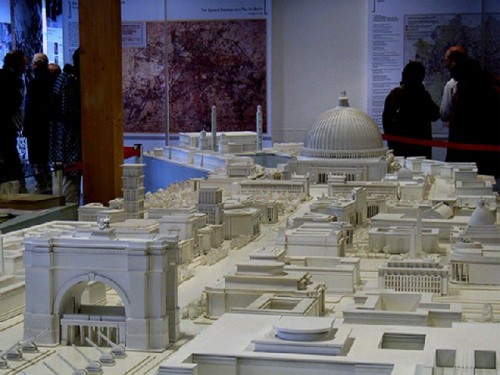

Which was not the case with another brilliant but less widely admired artist, Hitler’s chief architect, Albert Speer. He was responsible for designing the stadium and its dramatic lighting for Riefenstahl’s film “Triumph of the Will.”

Although an architect Speer played a vital role in prolonging the war when he was charged with rebuilding bombed munitions factories. During the final days he remained loyal to Hitler who kept him working on designs for the New Berlin. Of course, as is consistent with this landmark exhibition, in a style of grandiose, overblown, kitschy classicism. During years in Spandau prison Speer wrote the riveting memoir “Inside the Third Reich.”

It is the definitive account of how an artist can go terribly wrong. Like his boss, Speer evoked classicism as an expression of the Aryan ideal.