The Dishwasher Dialogues He Volunteered as a Kamikaze

Dwarfs Visited Chez Leroy

By: Greg Ligbht and Rafael Mahdavi - Dec 13, 2025

Rafael: There were a few memorable lesser-known regulars too.

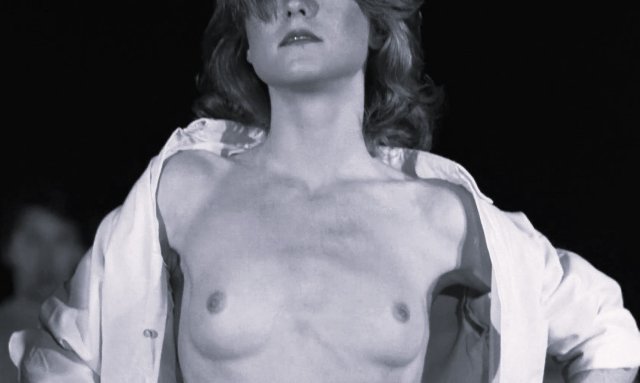

Greg: The ‘irregulars.’ Regulars to the bar but ‘irregular’ in other ways. Like Odele who took Tex’s tee shirt from the cloakroom one night, put it on, and pranced around the restaurant in it. When Tex—whom I had nick-named on his first day as a dishwasher because he was from Texas—demanded it back, she stripped it off, baring all, and dangled it in his face. Inexplicably, she was later hired as a waitress for a few months.

Rafael: The Spanish dwarf comes to my mind. I know that today you’re supposed to say short person.

Greg: That does sound better. After all, we are all irregular, but some people are treated more ‘irregular’ than others.

Rafael: Leroy knew I spoke Spanish and told me to treat the short guy well. I never knew how Leroy had met Juanito in the first place. I would hoist Juanito up onto the barstool where he sat with his feet dangling about two feet from the floor. I told him there were some famous dwarfs in Velazquez’s paintings, but Juanito couldn’t care less, all the little man did was ogle the waitresses. He was as horny as a snake. After about five scotches he got weepy and made nasty cracks in heavily accented French at the waitresses. Finally, Leroy would come out and say, ‘Okay Rafael, my man, time to get Juanito out of here’. And I would plead in Spanish with Juanito, but he wouldn’t budge. ‘Look’, I’d say, ‘I’m going to have to pick you up and take you out physically.’ ‘Oh yeah? You just try buster!’ And I would come out from behind the bar and lift him up off the barstool, kicking and shouting. I’d say, ‘I’m sorry, I really am, but this is what Leroy wants.’ Juanito then called me an hijo de puta, a son of a whore, and a cabrón, which, as I said before, translates as Billy goat. I would put Juanito down on the sidewalk at the corner of Rue des Martyrs. ‘Don’t come back tonight, hombre, because you’ll have to deal with Leroy.’

Greg: Then there was John, well-spoken and kind. A gentleman. Over the course of about six months, he came in regularly and would take his meal at the bar. He always came in alone. I think he enjoyed the opportunity to take in the American food and atmosphere and talk with other English speaking expats. We soon got to know him well enough, although clearly not everything. And he asked more questions than he answered. I had been living in Paris for about 3 years by then and the little he did say about what he was doing in Paris never added up. Leroy didn’t know him, and he didn’t seem to have many connections to anyone or anything else. We joked about him being in the CIA, but we said that in passing. He was happy to talk about the theatre and art and projects we were all into and he bought a copy of my poems, so he was cool. Then he was gone. Didn’t show up at the bar anymore. It turned out he was CIA. When he left Paris, he went to Iran. It wasn’t long after that the Iranian Islamic revolution happened with heavy coverage in the press. The American Embassy in Tehran was overrun, and all the staff taken hostage.

A few weeks later, someone came into the restaurant with a copy of the International Herald Tribune, and there was John in the photo, being released. He was one of a small group of people freed early because he was African American. Along with the women, the Iranians let him go because American blacks, they claimed, were victims of American oppression just like Iranians. The logic was impeccable.

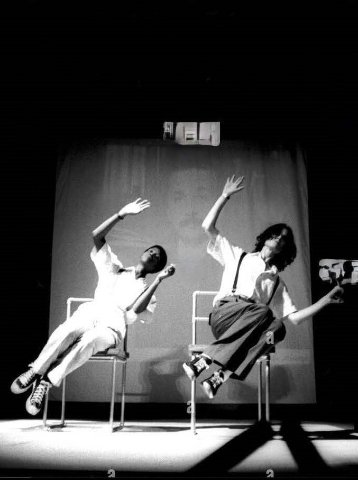

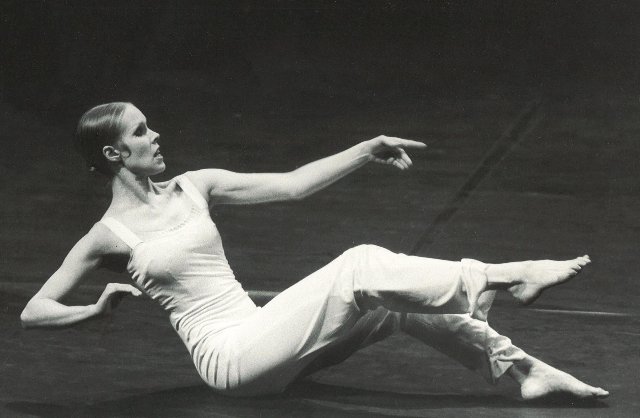

There was also the director and a couple of the crew from the Carolyn Carlson Dance Research Group at the Paris Opera. They came in, maybe a dozen times. She maybe once, just to eat. The others generally dropped by for drinks after a show. I quizzed them about the work and what they were doing. Told them about our work. They invited me to my first dance opera. Told me to be early. It turned out to be a seven-hour show. I had never been to the opera before. Nor had I ever attended a ballet, contemporary or not. I sat with them in the lighting booth. Great seats, but seven hours? I was not sure I could handle that. My first thought was how to get out during one of the breaks. It turned out to be a non-problem. I was completely blown away by the show. The sheer scale was astounding. Very different from the intimate pieces by Beckett, Ionesco and Pinter which had been my main influence. I followed up with trips to Pina Bausch’s Wuppertal Theatre at the Theatre de la Ville. And Robert Wilson’s Einstein on the Beach with Philip Glass’s music. Very eye-opening stuff at the time.

Rafael: And there was Namio too, a wealthy Japanese car salesman who also painted. He always treated us to champagne. He drank horrific amounts of scotch, and wine too. At closing time, I would call him a cab and gently slide him into it. One evening he told us how, as a young man, he had volunteered as a kamikaze pilot. It was a great honor for his family, he said. The day he was supposed to fly his suicide mission, the war ended, and he was grounded. It was terrible, Namio told us, so shameful for him and his family. In his anger and sadness and frustration, he stole a rowboat in Yokohama harbor and started rowing east, toward the US to exact his own revenge. He was pretty far out at sea when he was picked up by a US destroyer. The captain couldn’t get a word out of Namio, so the battleship kept going to San Francisco where Namio disappeared. There, he made his way into the burgeoning Beatnik scene around Ferlinghetti’s City Lights bookstore. Namio went to art school and miraculously became legal. His family must have hoped he had died at sea. They were surprised when they found out he was alive. He begged them to allow him to come home, and his family said okay, but for a short stay only. Namio couldn’t stay in Japan even if he was sort of a hero now to his family. His family relations got him a well-paid job in Paris, selling Japanese cars. All he had to do was take visiting Japanese car industry bigshots around Paris to visit nightclubs and whorehouses. He could hold his liquor well, but once in a rare while he’d kind of break down. The stern Japanese reserve would crack, and Namio would quietly say this is what Japanese patriotism gets you. ‘I know what I am, I’m not a painter, I’m a glorified man-Friday with a bit of the pimp thrown in.’

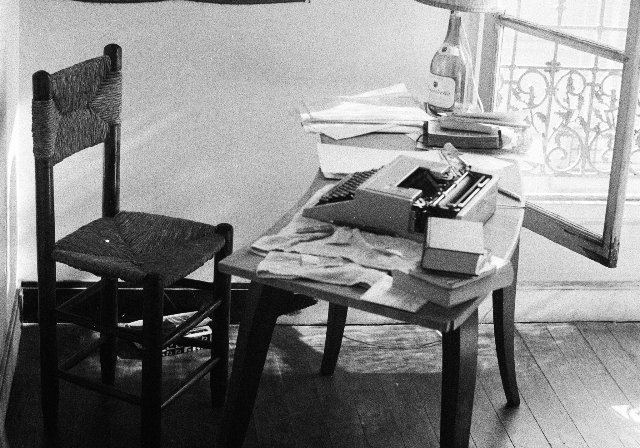

Greg: It wasn’t obvious when I first met Namio that he was doing battle with his own personal history quite so fiercely. It should have been more obvious: he was an older guy with money, living alone, still partying like an undergrad in residence. But what did I know? I had just arrived in Paris: a younger guy with no history to speak of, other than a handful of philosophy courses and a crumbling two-year relationship that would fully and mercifully die a few months later. It hardly compares to the unfathomable shame of failing to exit one’s life in a mass suicide attack from the sky. I assumed Namio was a successful painter, which was so cool, although I cannot remember what his paintings looked like. I recall he was a generous man with an amazing apartment in a fashionable part of Paris. I have memories of a couple of amazing parties at his place. Indeed, it was through one of these parties that I was given the two most important household items of my time in Paris. I had just moved out of the hotel on Rue Saint-André des Arts into my two rooms. The rooms were mainly furnished except there was no decent bed. After a few nights the couch was getting uncomfortable. One of the guests at the party said she was throwing out some things, including a bed and a typewriter. A typewriter? It was not electric, but, nevertheless, a working typewriter! I’d only brought pen and pencils on the airplane.

A couple of days later, Harry, his cousin and I went to her flat to pick up the items. It was on the other side of Paris. I only needed a mattress and the typewriter, but she insisted we take the box spring as well. We didn’t have a car or money for a taxi, so we threw ourselves on the mercy of Parisian public transportation. As Harry later told me; ‘We moved them from one side of Paris to the other by bus, all very much to the disgust of the other riders.’

I remember avoiding the stares and looks by just gazing out the window at the magnificent city which had just become my new home, hoping this awkward piece of impromptu street theatre would quickly pass.