Steve Nelson, The Bosstown Sound, Three

Boston Hype Fizzles, James Brown Sizzles

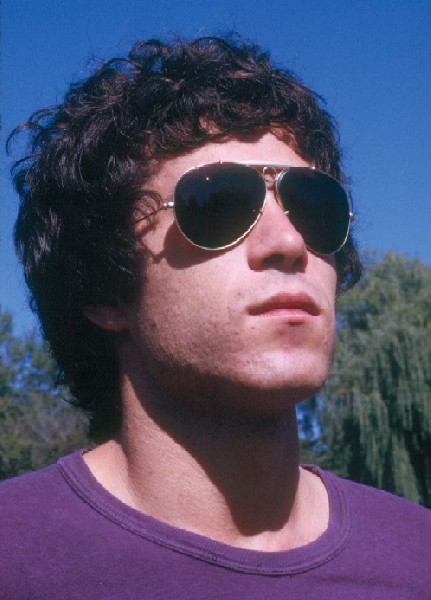

By: Steve Nelson and Charles Giuliano - Mar 06, 2011

Charles Giuliano: It’s early 1968 in our narrative, and you’re managing The Boston Tea Party, the rock and blues club owned by Ray Riepen, an eccentric lawyer from Kansas City who was living in Cambridge at the time. Despite the hostility of the powers-that-be in the city, the club is not only surviving after a year in business, but more popular than ever, and packed every Friday and Saturday night. Seeing what was going on in Beantown, MGM Records decided that there’s money to be made from the music scene there.

Steve Nelson: That’s right. Alan Lorber was a record producer, arranger and A&R man who had worked earlier in the Sixties with artists like Neil Sedaka, Connie Francis and Jackie Wilson, taking them from their ‘50s rock ‘n’ roll roots into a more orchestrated sound with strings. He thought Boston was ripe for the picking and brought several Boston bands to MGM: Ultimate Spinach and Orpheus, whose records he produced, and the Beacon Street Union, produced by Wes Farrell (the co-writer of “Hang on Sloopy” and later the producer of the Partridge Family).

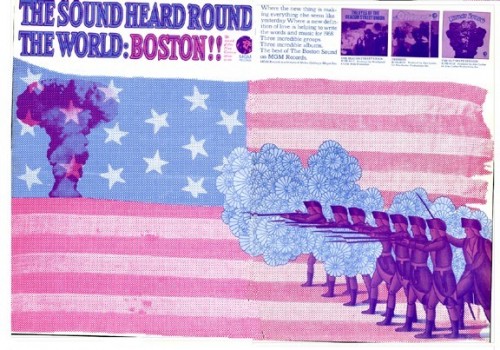

Lorber’s notion was that the “Boston sound” could be promoted as the next big thing after San Francisco bands like the Jefferson Airplane and the Grateful Dead, who came to prominence during the “Summer of Love” in 1967. MGM hadn’t signed a single band out of San Francisco, so they really pushed their new “Boston Sound” acts, playing on the Tea Party’s Revolutionary War name and calling it “the sound heard ‘round the world.” Newsweek ran a story headlined “Bosstown Sound,” which it called “the latest outbreak in the pop revolution,” and both “anti-hippie and anti-drugs,” which certainly was news to the people who went to the Tea Party!

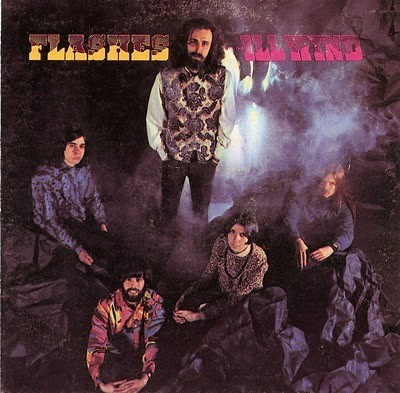

Another band in the Lorber-MGM stable was Chamaeleon Church, with future Saturday Night Live star Chevy Chase on drums. Not wanting to miss out, other labels got into the act. ABC signed The Bagatelle and Ill Wind, Elektra inked Earth Opera (with Peter Rowan and David Grisman), Vanguard had Listening, and there were many more.

The problem was that the idea of a “Boston Sound” was BS. There was no such thing. Those groups of course all had their own individual sound, as did other acts like The Hallucinations, who didn’t sign a deal. Lorber was a successful record producer, but he was from another era, and didn’t really get the kind of guitar-driven hard rock that bands in Boston and elsewhere were playing in the late Sixties. His most successful act from Boston was Orpheus, who had a softer sound based around its vocal harmonies.

The worst part of the whole business was that most of the bands who did sign deals were hurt by the record labels trying to cash in on what they saw as an East Coast gold rush. Some of them just weren’t ready yet for a record deal and a national stage. But putting out an LP was the dream of every new band, so you jump on it when the opportunity comes along, ready or not.

CG: During that period I was living in Roxbury and mostly involved with the underground paper Avatar. It was tough getting by and paying even a modest rent. So we only occasionally went to the Tea Party, but I do recall a promo event for Ultimate Spinach which was pretty hokey. I did get to see The Hallucinations. There were a number of free outdoor concerts and we saw bands or performers like Jaime Brockett. When I moved from Roxbury to Harvard Square there was a dramatic change, with free Sunday concerts on the Cambridge Common organized by Bob Gordon and Kenny Greenblatt with the support of the Episcopal church across the street. But that came a little later, so let’s get back to the Bosstown Sound.

SN: When you look at what went wrong with the Bosstown promotion, The Bagatelle was a good example. They were a great live act, a 9-piece mixed-race R&B band, with three lead singers sharing solos and doing some great harmony. Visually they were a striking trio – one tall, one medium height, one short. They performed a mixture of covers and originals, some penned by Willie Alexander (formerly of The Lost), who sang lead on his tunes.

Their producer was Tom Wilson, a black Harvard grad who had worked with jazz greats Sun Ra and Cecil Taylor. Then he produced Bob Dylan, Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention, and The Velvet Underground. He was probably most famous for taking Simon & Garfunkle’s straight acoustic guitar recording of “The Sounds of Silence” on their first LP and, unknown to Paul and Art, overdubbing electric instruments to turn it into a smash folk-rock hit and make them big stars.

I guess Tom figured he’d do the same for The Bagatelle, adding some strings. Well, that was a disaster, and the group soon broke up. Tom also produced Ill Wind, but fortunately with no strings attached. Their sole LP, Flashes, never went anywhere at the time, thanks to a defective first pressing and poor support from the label, but now it’s considered a psychedelic classic.

That was pretty much the fate for the Boston bands of that era. None of them had a hit record, although Spinach and Orpheus did each put out three LPs and had a moderately successful but short career. For most of them, it was one record and done. In some cases it was due to poor production, in others because they weren’t very good to begin with, or hadn’t developed to the point where they were ready to record.

Writing in Rolling Stone, Jon Landau, who came out of the Boston music scene himself (and went on to become Bruce Springsteen’s manager), dismissed the whole thing under the headline “The Sound of Boston: Kerplop.” But I might add immodestly that he had some nice things to say about the Tea Party, calling it “consistently well-run” and adding that it was “popular with out of town groups because of the professional treatment they receive.” And that really was what made the Tea Party a success, being a great place for musicians to play and audiences to go.

CG: As I recall, the “Bosstown” hype for a time created a stigma for rock bands in the city. Of course, as Dave Wilson and I have extensively explored, there had been a thriving folk scene, with many clubs and coffee houses. With its enormous critical mass of college students in the Boston area, there was an incredible potential audience for rock. So the gradual emergence of a great rock scene and locally-grown bands was inevitable.

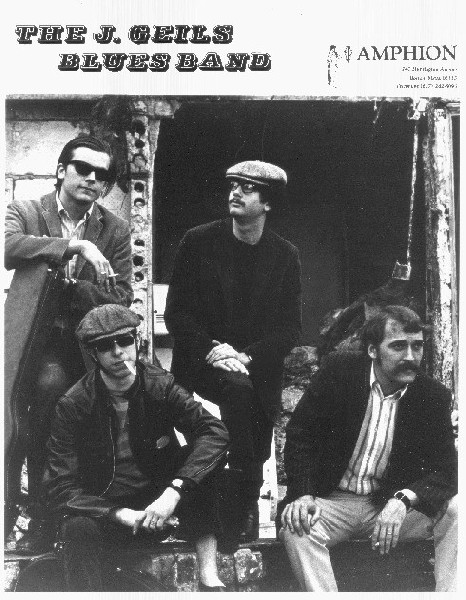

SN: Even bands not part of the MGM hype got tarred and feathered with the same “Bosstown” brush, so it was difficult for them to be heard on their own merits. But when the hype died down, Boston in fact turned out to be a great incubator of musical talent, producing acts like J. Geils, Aerosmith, and The Cars. The original J. Geils Blues Band played the Tea Party, and then debuted their new lineup there when lead singer Peter Wolf and drummer Stephen Jo Bladd joined them from The Hallucinations. Steven Tyler, Joe Perry and Tom Hamilton of Aerosmith talk about having seen shows at the Tea Party and being inspired to start a band, as were Barry Goudreau and Sibby Hashian of the band Boston.

The Cars came along a little later, but their drummer David Robinson first played in the protopunk band The Modern Lovers with Jonathan Richman, who as a teenager was a rabid Velvet Undergound fan and never missed their gigs at the Tea Party. I couldn’t even begin to list here the many important artists who came out of Boston and New England, in all genres of music. That’s why we’re creating the Music Museum Of New England, to honor that talent.

CG: I had an interesting relationship with the Modern Lovers. Perhaps we are jumping out of your chronology. In 1973 my Cambridge neighbor Arthur Gallagher was looking for a band to bring to Bermuda to perform during Spring Break. His family owned a hotel called the Inverurie. I suggested the Modern Lovers. For the week I got to stay with Arthur and his Mom. They performed every night that week. Bermuda organized beach parties and activities for the kids. The band performing at all those events were the Bermuda Strollers. They had an anthem “Wings of a Dove.” We tried but couldn’t get the ML onto any of the programs. The turn out at the hotel was sparse. But the word spread and some kids returned every night and brought their friends. By the end of the week we had a pretty good house.

Today the band is regarded as a cult classic. During the Bermuda gig they had a solid rock sound that included the anthem “Roadrunner” as well as unique songs like “She Cracked” and “Pablo Picasso.” Later Richman wanted to go in more of an acoustic folk direction. I recall him playing a capella in the recessed entrance of the Coop in Harvard Square. He clapped his hands and slapped himself to create a rhythm. The original Modern Lovers broke up because of artistic differences. He created the music for the film “There’s Something About Mary.” In addition to David joining The Cars, Jerry Harrison, who played keyboards, joined Talking Heads. The bass player was Ernie Brooks who would later work with David Johansen, Arthur Russell, Elliott Murphy, and Gary Lucas.

Arguably the Modern Lovers were among the bands that marked a transition from the demise of The Bosstown Sound and the emergence of the later developments of bands that marked Boston as a significant player in the national music scene. Let’s return to your involvement with the Tea Party. You are among the original sources capable of giving us a detailed and accurate account of that period.

SN: In retrospect, it’s ironic that before Alan Lorber “discovered” Boston, MGM already had on its Verve subsidiary label the most important band associated with the Tea Party at that time, The Velvet Underground. After John Cale played his last gig with the Velvets at the Tea Party in September 1968, the band’s ties to Boston grew closer when they added local boy Doug Yule, who had played the Tea Party with the Grass Menagerie. But MGM never had a clue what to do with the VU, and damaged the band’s chances for success with its inept distribution and promotion. So they left to sign with Atlantic’s Cotillion label for their final LP, Loaded.

CG: Did the Bosstown Sound promotion leave any scars on the Tea Party, since you booked many of the bands who got caught up in it?

SN: Not really, even though we were in the middle of it. The Bagatelle, The Beacon Street Union, Ill Wind and Ultimate Spinach all had played the Tea Party before the promotion broke, so of course I booked them when they released a record. It was the bands who were the victims of the “Bosstown” massacre, and in most cases didn’t survive it.

The Tea Party, on the other hand, was doing so well that in the spring of ’68 we decided to add to our normal Friday-Saturday schedule a series of one-night-only Thursday gigs, with the likes of The Yardbirds, B.B. King, Procol Harum and Traffic. The first one was on April 4, headlined by Muddy Waters and his band, featuring Otis Spann and Little Walter, with The Hallucinations opening.

Muddy had played many gigs at the great folk and blues venue Club 47, one of my old haunts. When they played there, Muddy and Howlin’ Wolf and other musicians used Peter Wolf’s nearby Harvard Square apartment as a dressing room, since the club really didn’t have one, and those guys went on stage in suits and ties, not jeans and t-shirts.

Struggling financially, and unable to compete with the much-larger Tea Party for bookings, the 47 had shut down just days before. I was thrilled to have Muddy play for us, although I did feel bad about helping to put the 47 under. But there was no time for guilt trips that day, because we got word that Dr. Martin Luther King had been assassinated. There were riots in the streets of many American cities, including Boston, but inside the Tea Party the racially-mixed crowd was totally peaceful, and Muddy sang the bluest blues I’ve ever heard, more of a wake really than a concert.

This was less than five years after President Kennedy’s assassination, so there were still painful memories of that, especially in his home town of Boston, and people had a hard time coping with the murder of another leader they admired. It was particularly painful to me, because I had been a civil rights activist, and because the son of my parents’ best friends, whom I went to college with at Cornell, was one of the three civil rights workers murdered in Mississippi in 1964, Mickey Schwerner.

CG: Actually Boston was unique regarding riots when Dr. King was assassinated. It so happened that James Brown was booked to play Boston Garden the next night, Friday. Mayor Kevin White asked public television station WGBH to air the concert so as to encourage people to stay home, and it was rerun several times. White acknowledged Brown at the show for helping to keep the city calm. I was living in Roxbury with my girlfriend Arden Harrison and we watched it on our small black-and-white TV. We were concerned, of course, living in a black neighborhood. But there were no incidents, and I recall hearing the JB broadcast playing in adjacent apartments.

SN: The Garden was actually going to cancel the concert. But Tom Atkins, Boston’s first black City Councillor, convinced the Mayor that it would only make matters worse if thousands of people arrived at the Garden to find the show called off. So it was decided that afternoon to let it go on and televise it, as a way to satisfy ticketholders and keep everyone else off the streets in front of their TVs. By the way, everybody saw it in black-and-white, because the broadcast came about so suddenly that WGBH didn’t have time to install cables at the Garden to transmit the show in color.

At the Tea Party that Friday night we had The Amboy Dukes, featuring guitar hotshot Ted Nugent, and opening act Tangerine Zoo, another local band with a new record. Under normal circumstances that would have drawn a full house, but not surprisingly the crowd was sparse. I always made a point of catching part of our shows, but that night someone brought in a TV, and several of us stayed in my office and watched the Garden concert. It was a riveting experience, because in those days you never saw anything on TV like a live James Brown concert. No wonder the streets of Boston were virtually deserted, with everyone home glued to the tube.

But we were not unscathed by violence. Ravi, one of the kids who worked at the Tea Party, and in fact was pictured dancing there in that “Bosstown” Newsweek article, lived in Roxbury in a community of immigrants from India. Riding his motor scooter home after the Muddy Waters show, he was knocked to the ground when someone in a mob threw a brick and hit him in the face. They moved in on him and were probably about to beat him up, if not worse, when one of them yelled, hey wait, stop, I know him from the Tea Party. So they let him go.

Despite his face being grotesquely swollen up, he showed up for work the next night. The Tea Party was a second home to Ravi and all of us who worked there and many of the people who went there. We even had our own in-house guru of sorts, Mitch Blake. His actual job was to oversee and maintain the physical premises. But Mitch was a very spiritual and peaceful guy who stayed centered in the middle of all the craziness at the Tea Party, and helped to keep us centered.

Shortly before the King assassination, in late February, we had put on a Sunday night benefit at the Tea Party for a community center in Roxbury run by Operation Exodus, a voluntary program to bus African-American kids from inner-city schools to predominantly white schools. The show featured The Chambers Brothers, a mixed-race band with four brothers from Mississippi and a white drummer, who fused soul and gospel with psychedelic rock.

Many of the people in attendance came in from the suburbs, and had never been to anything like The Boston Tea Party before. Part of the event was my first and only “performance” at the club, a multimedia show contrasting life in the ‘burbs with that in the ghetto. To prepare for it, one afternoon I had walked from the Tea Party through the South End and into Roxbury, taking color slides of the people and the neighborhood. Ironically, one shot was of a wall poster for a James Brown concert that had played the Garden in January. I also spent an afternoon with my camera in the very white suburb of Wellesley, and then put together a show, of images backed with a sound track of LP cuts, that got darker visually and musically as it went on.

By the end it got pretty intense, and when it was over and the house lights went on, the crowd was totally silent. Wow, I thought, I really blew it. I was more relieved than proud to hear them finally applaud, and loudly. The show closed with a folk singer doing “Amen.” Amen, indeed. Six weeks later, King was dead, race relations changed, and you wouldn’t even think of wandering through Roxbury with a camera. “Hey white boy, whatcha doin’ uptown?” in the words of The Velvet Undergound.

The Tea Party was changing too. It’s reputation in the music business was growing, and it had become a must-play stop for bands on tour. The crowds, now almost all white, weren’t dancing much anymore, just listening to the music. And I couldn’t know it at the time, but my days there were numbered.

Links

Video clips of James Brown concert at Boston Garden, 4/5/68

"Unseen Boston," Steve Nelson's 1968 photos of the South End and Roxbury

Reference

James Sullivan, The Hardest Working Man: How James Brown Saved the Soul of America (Gotham House, 2008) (the definitive book on the Boston Garden concert and on JB as an icon of black America)