Carl Belz Two

Running the Rose Art Museum During Hard Times

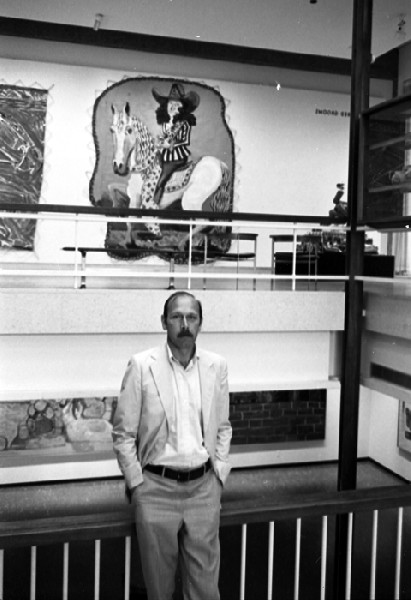

By: Carl Belz and Charles Giuliano - Jun 04, 2011

Charles Giuliano You describe taking over at the Rose with an exhibition budget of some $4,000 a year for five or six museum level exhibitions.

To what extent was that a part of the Susan Sacks and Kathy Powers bank robbery and murder and an era when they and Brandeis graduates like Angela Davis and Abbie Hoffman were on the FBI ten most wanted lists?

The result was that many of the Brandeis donors turned instead to supporting Israel and other philanthropies.

By the 1970s and your watch at the Rose it would seem that the utopian vision of creating a great Jewish/ Liberal university was facing a harsh and more conservative reality check.

You told me in the past that in those hard times Evelyn E. Handler, President of the university from 1983–91, spared the permanent collection of the Rose. Of course that changed under now retired Jehuda Reinharz.

Faced with that limited budget you were forced to make tough decisions. A positive consequence was supporting emerging and regional artists.

Discuss the process of developing a program when you first took over with such limited resources. Part of that was surely a learning curve of getting up to speed with a dynamic and fast changing Boston art world. In 1969 the artists organized the first open studios in the nation as the Studio Coalition. By 1971 the Boston Visual Artists Union, again a national first, was up and running eventually with some 1,500 members. There was the famous Flush with the Walls happening in the men's room of the MFA. Shortly after that the museum announced the appointment of Kenworth Moffett and the founding of a department of Twentieth Century Art.

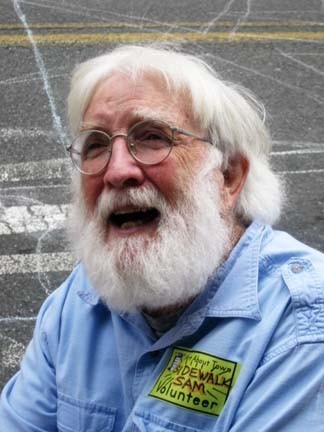

To what extent were you a part of these emerging events? How did they influence your thinking and bring you in contact with individual artists? Early on you showed Robert Guillemin, one of the activists, before he became Sidewalk Sam. Katherine Porter, who now lives near us in Vermont, talks about the importance of your support and her Rose Show. Todd McKie was one of the Flush with the Walls activists. For one of the later, annual Foster shows, you featured Todd and Judy McKie. Today Judy is regarded as one of America's finest studio furniture makers.

There is a perception that Boston artists are forever marginalized by the New York School. Do you follow the truism that if an artist lives and works in Boston the work can't be all that good?

How did the Rose under your watch survive and prosper despite the obvious limitations?

For a time in the 1960s and 1970s Brandeis was regarded as one of the most politically radical campuses in the nation. During the early years it was able to attract a remarkable faculty because so many were black listed during the era of McCarthyism. It was a university focused around writers for the Partisan Review and great thinkers including Herbert Marcuse, Abraham Maslow, Irving Howe, Max Lerner, Philip Rahv, Paul Radin, Leonard Bernstein, Irving Fine, Leo Bronstein. I attended many Sunday afternoon broadcasts by Eleanor Roosevelt. There were lectures by Zen philosopher Alan Watts, black writer, James Baldwin, and communist party leader Gus Hall. There were memorable concerts by Pete Seeger and Joan Baez.

It resulted in a radical student body including Abbie Hoffman, Angela Davis, Susan Saxe and Kathy Powers. I flunked freshman chemistry but my lab partner blew up a bank as a Weatherperson.

While I am mostly a liberal in political views I see myself as an art radical. Brandeis trained me to be inventive and follow the road less traveled.

After the extreme politics of the founding years the utopian vision of a great radical Jewish university was tarnished and modified. How did that backlash among trustees and donors filter down to the Rose Art Museum?

Carl Belz I've always felt that radical student unrest must have cost Brandeis in the late 1960s. Just as it likely cost lots of other institutions, except that Brandeis always lived closer to the financial edge than other, older institutions that had more endowment and a deeper alumni base. I still think that's why the rug was pulled out from under Bill Seitz in 1970-71, for instance--you know the story: when the financial pressure mounts, the arts are the first to go. What I knew for sure was that Brandeis's financial situation was always linked with what was happening in Israel. The effect of the Yom Kippur War was felt everywhere in the university in 1973 when fundraising was said to have dropped to zero in 24 hours. And so it was throughout the 20 years I spent there.

Yes, the utopian vision of a great Jewish/liberal university sort of got displaced in the 70s. Brandeis became less radical, more like a whole bunch of other good, smaller, liberal arts colleges and universities. Maybe that evolution was natural, the effect of the passing of the founding generation--the New York-based, Jewish intellectual, Partisan Review generation. Or am I romanticizing? In any case, what happened was not unlike what happened to the utopian vision of modernism in the 70s as it got displaced by the leveling effects of pluralism and postmodernism.

How to develop an exhibition program without dough? (1) Utilize the talent in your own backyard. In my first year at the helm, I did solo exhibitions of work by Flora Natapoff (whom I met through English Department colleague Alan Levitan) and Paul Brown (a friend, as well as a member of the Department of Fine Arts). Good shows, both of which I fully believed in, but I came to feel uneasy about them afterward. They put a museum imprimatur on a pair of individuals who were at the time just coming into their first maturity. Which struck me as unfair to them in seeming to pronounce them successful when what I intended was to provide them exposure. In succeeding years our annual Boston area exhibitions were invariably group shows, comprised of three to six artists we got to know during the studio visits we made on an ongoing basis. I never liked group shows that included many artists, each represented by one or two objects. I wanted to give each artist a chance to show what he or she was up to. We did those shows as long as I was director. They helped enormously in establishing our credibility within the artist community and I remain proud of their legacy in the Rose history. That they were less expensive to produce than imported from afar was in the end but a fringe benefit.

(2) Raise funds privately, outside what the university provided. This we did by starting the Patrons and Friends of the Rose Art Museum at $250 or $125 per membership, with Lois Foster as Chair and Chief Fundraiser. Our goal was to raise enough dough to support annually one major exhibition, featuring an artist of national significance, including an appropriately ambitious catalog, the works. The first was "Alex Katz in the Seventies," which was 1977, then Frank Stella, and Mel Ramos, and Helen Frankenthaler, and on it went, becoming as distinguished tradition in itself as the years passed. The "Todd McKie and Judy Kensley McKie" and "Barnet Rubenstein" exhibitions were part of that series, two of the best shows I ever did, and to think--they both featured "local artists'! BTW as the membership program grew it supported increasingly not just one exhibition, but the entire exhibition program. Its success got us to the point where the university decided we should support ourselves even more fully, without relying on any university funding at all. Thus did we become victims of our own success. Talk about postmodern irony!

(3) Show the permanent collection. I always got a kick out of seeing museums close for a year or more in order to "reinstall the permanent collection," as the sign on the door read. We used to reinstall the permanent collection a couple of times each year without ever missing a beat. It was always a treat, there were countless exhibitions right there at our fingertips, it made the job fun. And it hardly cost a dime.

Boston versus New York: Here's a remembrance you'll get a kick out of vis a vis Boston/New York. Remember when the ICA opened in its new home up on Boylston Street in the old firehouse? It was 1974 as I recall, and the opening show was what? A New York School show guest curated by Dore Ashton. And what was the second show? "Painted in Boston" curated by guest curator, yours truly, a local boy who'd just been named director of the Rose Art Museum, Carl Belz. There you have it: New York first, Boston second, it tells the story of those days, doesn't it? But it's not my story, I never bought into it--which I believe is clear from my record. As Casey liked to say, "You can look it up."

I could go on but enough's enough for today.

CG You state "The first was "Alex Katz in the Seventies," which was 1977, then Frank Stella, and Mel Ramos, and Helen Frankenthaler, and on it went, becoming as distinguished tradition in itself as the years passed.”

I recall them vividly. Didn't you get a lot of negative feedback from the feminists on the Mel Ramos exhibition including from your second in command Susan Stoops. I got to interview Frankenthaler when she was installing. Her star has since ascended and nobody today remembers much more than "Mountains and Sea."

I had an amusing experience with Stella. He was a visiting artist and Bill Seitz invited me to meet him over lunch in the faculty club. I would ask a question which Stella mumbled and glossed over. Seitz would jump in and say "What Frank means is..."

Then Bill urged me to go along with Frank and observe his class. We chatted a bit on the way to the studio. Our fathers were doctors and knew each other. That failed to impress him.

In the studio Frank took off his jacket and tie and rolled up his shirt. The students drifted in while he sat on a stool not saying a word.

This went on for some time. A student approached and showed him some geometric drawings in a sketch book. He mumbled something more or less encouraging. She went away and I left. It was not much of a learning experience and I thought long and hard about the notion of the impact of a big shot visiting artist.

Based on the ersatz experience I wrote a piece for Boston After Dark with a headline "Stella Means Star in Italian." It made it into some published bibliographies.

You talk about working with the permanent collection. During one of our many meetings and interviews I asked about the Gevirtz-Mnuchin collection founded by Sam Hunter. I believe it was about $50,000 for some twenty works. I asked Sam about it a few years back during a lunch with then director Joe Ketner.

As Hunter put it all of the money might have been used to purchase one or two works by an established artist. He opted instead to collect works by then emerging artists.

For reference you pulled out the acquisition folder. It was amazing to see works purchased for between a few hundred and a five thousand dollars. The most expensive was the Jasper Johns.

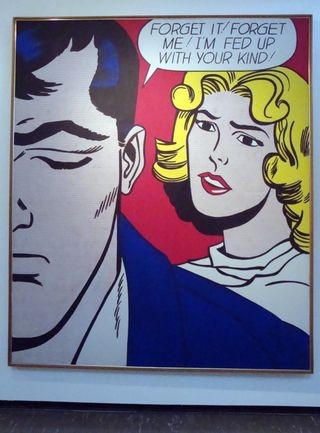

At the time, this may have been the 1980s, I asked you for an approximate evaluation of those works. You estimated some $13 million and I believe the most valuable proved to be the Roy Lichenstein. The hand painted 1962 Warhol "Do It Yourself Sailboat" was later swapped for a large silk screen of "Saturday Night Disaster." I regret that an early deKooning woman, not from Gevirtz-Mnuchin, was traded for a later work. The early woman seemed more important even though smaller, early and less imposing.

While you had no money, starting with and annual budget for exhibitions of just $4,000 a year, you were presiding over what has come to be regarded as the most important collection of contemporary art in New England. The more so in view of the fact that the Museum of Fine Arts didn't start to collect contemporary art until 1971. Kenworth Moffett collected abstract art and color field painting and had no interest in pop and minimalism. So the MFA missed the boat in an area of great strength for the Rose.

To what extent did you get to build on the collection of the Rose? It was past the peak of the Hunter/ Seitz era. But surely the critical mass of the collection attracted donations. You were supportive in accepting works by emerging artists including myself. I also gave the Rose works by Boston artists Stoney Conley, Lee Newton and Paola Savarino.

That was years ago and today I have a significant collection. I always imagined that one day I would leave works to the Rose. The recent Rose fiasco tore my heart out. The museum has always been so important to me as it is to many alumni. I feel betrayed and violated and have vowed never to set foot on the campus. It has been a like a death in the family.

While I am a minor collector I am sure there are alumni with major collections. By attempting to raid the Rose during a time of economic crisis Yehuda Reinharz has in fact costs the university untold millions in future donations to the museum.

Later when you had built up some acquisition funds you told me of a decision to focus on drawings by sculptors. At that time they were relatively affordable.

Can you share with us some of your acquisitions and donations? At the end of your tenure how large and important was the Rose collection?

CB Collecting: Like any museum, large or small, the Rose depended on gifts for much of its collection growth. What became clear to me from early on, however, was that a museum also needs acquisition funds in order proactively to shape its collection and demonstrate tangibly its mission. It thereby leads its audience, including potential donors of objects, by its actions, not just by its words. But there are naturally limits on what you can accomplish. Like Brandeis generally, the Rose constituency had a critical mass in New York as well as Boston. For the New York collector/donors, this meant we were in competition with MoMA, the Whitney, the Met et al, places where donors would get a lot more bang for their buck than they would by giving to a little museum in Waltham.

So it was exciting when we were given $500,000 by the Trustees of the Rose Estate to establish an acquisitions endowment, which happened around 1980. We called it The Rose Purchase Fund, and it yielded about $40K a year. That sounds like small change today, and it was by no means a fortune as the market began to percolate back then, but it meant the museum would have acquisition funds in perpetuity for the first time in its history. Which I felt was an achievement. So we then tried to address a series of concerns as we commenced the shaping process.

(1) There were gaps to fill. Minimalism, for instance, which came along after Sam Hunter's ground-breaking Gevirtz-Mnuchin purchases (though there could have been early Stella, whose absence from that collection has always perplexed me). So I bought a Robert Mangold early on, as well as a major Richard Serra drawing. And later, when the acquisitions endowment had been increased via deaccessioning, we bought wonderful Agnes Martin and Joseph Marioni paintings.

(2) We were always conscious of shaping the collection in tandem with our exhibitions program. So we regularly acquired works by area artists via gifts and purchases. The first work I acquired with the Rose Purchase Fund, for instance, was a large watercolor by Todd McKie. And there came to be many others, including Kathy Porter, Barney Rubenstein, Roger Kizik, Judy Kensley McKie, John Thornton, John McNamara, Ellen Gallagher, Jim Weeks, John Imber, and so the list goes on. In the 90s, in connection with Rose curator Susan Stoops's "More Than Minimal: Feminism and Abstraction in the 70s," we purchased postminimalist works by Jackie Ferrara, Ana Mendieta, Mary Miss, Michelle Stuart, Hannah Wilke, and Jackie Winsor, an historical grouping as significant as any in the entire collection.

(3) Not having a lot of storage space for sculpture, I started a collection of sculptors' drawings. Serra did double duty there, but I provided company for him with David Smith, Joel Shapiro, Jene Highstein, Bill Tucker, Chuck Holtzman, Bob Rohm, Claes Oldenburg, plus others whose names escape me at the moment. But together they make a really nice exhibition that I loaned to other institutions on a couple of occasions.

(4) Ever mindful of photography's relentless impact on the contemporary arts, we worked steadily to build a respectable collection that had started close to square one. One of my favorites was a Cindy Sherman from a series of "fold-outs" she did in the early 80s. It shows a young woman lying on her bed, looking forlorn as the phone near her head refuses to ring. It's supposed to be a postmodern quote referencing the media or something like that, but I bought it just because it reminded me of my life as a B movie. Another favorite was John Kennard's "Little League Field," a photograph of a deserted baseball field in rural upstate New York seen from behind home plate. Except for me the field wasn't deserted, it was filled with the ghosts of my youth.