Artist Krzysztof Wodiczko

Harvard Double Header

By: Mark Favermann - Jan 12, 2022

Both of these exhibits are examples of the artist as a 21st-century shaman — a prophetic, as well as a creative, force.

Interrogative Design: Selected Works of Krzysztof Wodiczko at the Druker Design Gallery, Harvard University, through February 20. In conjunction with Krzysztof Wodiczko: Portrait at the Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, through April 17.

When I first heard Krzysztof Wodiczko eloquently speak about his often visceral, visually provocative approach to art, I couldn’t help but see his work as an environmental extension, writ large, of the genre of Polish Poster Art. These highly graphic, at times cartoon-like images somehow found their way into the streets and galleries of the Eastern European bloc, countries that, during the Cold War, were puppet regiments of the former Soviet Union.

From the ’40s through the ’80s, Polish Poster design attracted international attention and admiration. They were commissioned to promote cultural events, including opera, theater, films, and visual art exhibitions. Although artists were forced to follow the strictures of the state, these posters were characterized by sophisticated imagery, often reflecting clever surreal or expressionist tendencies. The use of bold colors and strong gestures offered opportunities for biting satire. These posters were not overtly ideological, but they often expressed the artists/designers’ powerful, though necessarily oblique, criticism of the political environment.

Even though they could draw on images of violence and sexuality, these posters were “officially” sanctioned and distributed. Government bureaucrats (out of indifference? old-fashioned incompetence?) turned a blind eye to the scathing commentary contained in the majority of these posters. To me, Krzysztof Wodiczko’s less circumlocutory art expands on this tradition of dissent.

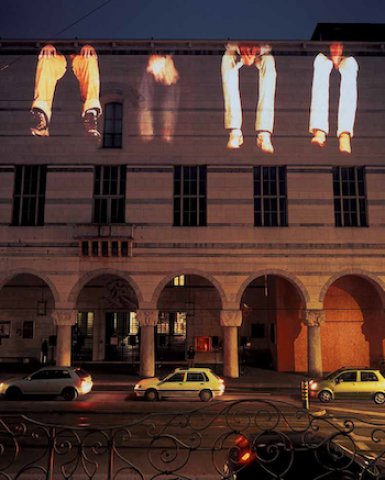

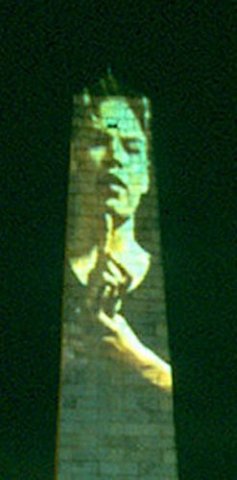

Wodiczko was born April 16, 1943, at the end of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising (clearly, another source of his vision). He is a Polish-American artist celebrated for his projection of large-scale slides on historically significant facades and monuments. During his career, he has created more than 80 public displays of this kind throughout the world. His visual art’s major themes include: narrations about war, conflict, trauma, memory, human communication, and personal history.

Trained as an industrial designer, Wodiczko calls his creative approach a form of “Interrogative Design.” He skillfully combines art and technology in a critical practice that concentrates on giving legitimacy to cultural and social issues that are often ignored in the context of design, such as the struggles of marginal communities, particularly immigrants. For example, since the late ’80s, setting up his projections has called for the hands-on participation of the marginalized and/or estranged. Simultaneously, he has also been designing and creating a series of “nomadic instruments,” vehicles that are used by homeless people, immigrants, and war veterans to protest their conditions.

Wodiczko lives and works in New York City and is currently professor in residence at the Art, Design, and the Public Domain Masters of Design program at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. Previously, he served as the director of the Interrogative Design Group at MIT and the Center for Advanced Visual Studies (CAVS). He has been a professor in the Visual Arts Program since 1991. Over the years, he has also served as a visiting professor at the Warsaw School of Social Psychology. His work has been extensively exhibited internationally. He was a recipient of the 1998 Hiroshima Art Prize “for his contribution as an international artist to world peace.” In 2009 Wodiczko represented Poland in the Venice Biennale and in 2017 he was given a retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Seoul.

The Graduate School of Design exhibit Interrogative Design: Selected Works of Krzysztof Wodiczko introduces visitors to diverse and wide-ranging examples of the work of one of the 21st century’s most remarkable artists. On the one hand, the exhibition emphasizes Wodiczko’s skill at weaving together art, design, social engagement, and innovative technologies. But the show also demonstrates how he creates maps by projecting the images of marginalized individuals onto urban architecture, memorably etching new memories onto existing monuments. Background is provided into the origin of each project on view, which helps viewers appreciate the thoughtful precision of Wodiczko’s creative process. It is difficult not to be moved by the human stories that drive his disruptive gestures, the deep pain his public art gives voice to.

Wodiczko is best known for his large-scale slide and video projections onto architectural facades and monuments that usually have an audio component as well. However, the GSD’s Interrogative Design also usefully displays a set of his process drawings and objects, which have, understandably, been much less visible than his large-scale installations. These are invaluable aids in appreciating the demands of his artistic process as well as in understanding the appeals made by his aesthetic provocations. The exhibition’s title, “Interrogative Design,” sums up the challenges posed by his creative process: he locates a subject or topic, researches an urban area, selects an architectural element, navigates local government power structures, and cultivates community trust.

In addition to objects and works shown in the Druker Design Gallery, Harvard GSD’s Frances Loeb Library contains a timeline of Wodiczko’s activity, including photographs of earlier slide projections in public spaces. Of particular interest: there’s an in-depth look into the making of the Voices of Bunker Hill Monument (1998) project, supplying fascinating details into what it took to create this vital (Charlestown) intervention.

At the Harvard Art Museums, Krzysztof Wodiczko: Portrait is a work commissioned from the artist. The goal of this installation is to examine questions about the state of American democracy today. Video recordings of students and young people from Harvard University and the Boston area who have been asked about current dilemmas are projected onto the Harvard Art Museums’ iconic portrait of George Washington (c. 1795) by Gilbert Stuart. This interactive artwork stimulates a relevant exchange of clashing views at a vexing time of heightened political division. In conjunction with the Portrait commission, two of Wodiczko’s drawings — recently acquired by the museums — are also on display. The works are studies from the artist’s prescient Homeless Vehicles series, which was created in the late ’80s to address the emerging needs of individuals who were experiencing homelessness. It was also meant as a response to former US president Ronald Reagan’s “trickle down” economic policies. (Déjà vu all over again.) Noticeably, the HAM’s elegant gallery space, which hosts Krzysztof Wodiczko: Portrait, is just not expansive enough to comfortably present Wodiczko’s many-layered art.

Wodiczko’s work is nothing if not accessible. His images directly engage cultural issues and problems that confront contemporary society. Its power derives from how fundamentally his visuals question authority; he transforms public art into a rhetorical tool dedicated to making people think critically about the world around them. Still, beyond aesthetics and political context, one senses an intrinsic spirituality to Wodiczko’s art.

According to Wodiczko, his art represents “the present time in which the past and the future dwell.” Both of these exhibits are examples of the artist as a 21st-century shaman — a prophetic, as well as a creative, force.

Courtesy of Arts Fuse.